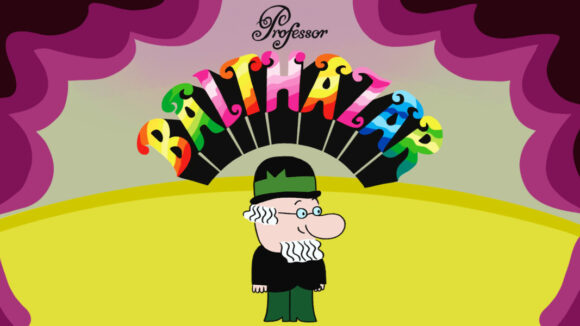

1960-70s Zagreb School Icon Professor Balthazar Is Making The Jump To Video Games

Between 1967 and 1978, a lovable scientist named Professor Balthazar (also known regionally as Profesor Baltazar) traveled the globe with a magic machine, dropping into troubled towns and anxious neighborhoods to solve everyday problems with creativity, patience, and a dash of wonderfully illogical ingenuity.

Produced within the orbit of Zagreb Film and the Zagreb School of Animation, the series remains a smart piece of educational pop art: eccentric but accessible, playful but principled, and quietly radical in its belief that most conflicts can be resolved without villains, violence, or humiliation.

In a world that rarely stops vibrating with drama, Balthazar’s worldview still feels bracing. The episodes emit messages of peace, environmentalism, and the importance of cooperation and community — gentle parables delivered in a deceptively simple visual language that remains instantly readable decades later.

And yet, for all its lasting warmth and influence, the professor has largely been silent since 1978. The shorts still circulate online, but “new” Balthazar has long belonged to the realm of nostalgia — until now.

Gamechuck, a Croatian video game development studio, has been working on resurrecting the professor as an interactive experience titled Professor Balthazar: The Interactive Season. It’s an intriguing proposition: not only a revival, but a revival that has to behave like Balthazar. It can’t merely borrow the look; it has to inherit the logic—curiosity over conflict, cooperation over conquest, invention over antagonism.

Aleksandar Gavrilović, founder, CEO, and co-owner of Gamechuck, frames the timing with a wink: “The best time to revive a 1960s cartoon character is right now, and the second-best time is February 15, 2026, when we launch the Kickstarter campaign.”

Behind the joke is a larger claim: even if the character isn’t constantly in the spotlight, the Zagreb School’s influence has never really disappeared. “Although the character himself might not be in the spotlight anymore,” Gavrilović says, “the entire Zagreb School of Animation really does have a lasting influence on cinematography.” The school, which “rocked Europe in the ’50s and ’60s,” also produced Ersatz (1961), the first animation Oscar awarded to a non-English-speaking country. Its influence, he argues, can be traced forward into mainstream animation—from “character design in Dexter’s Laboratory” to the “design of the soul guides in Soul (2020).”

But if the Zagreb School’s aesthetic echoes widely, its most commercial and long-lasting project was Professor Balthazar itself, “spanning four seasons and airing across the world.” Gavrilović even points to an unexpected historical detour: when Chuck Jones was tasked with creating his “Curiosity Shop,” a rival to Sesame Street, he “took the cartoons of Professor Balthazar and added his own live-action intros to each, narrated by an actor dressed as ‘Baron Balthazar.’”

A larger question follows any adaptation: how does an old philosophy survive a new medium? Gamechuck’s answer is to treat the show’s core elements as non-negotiable. “We’re trying to be as respectful as possible in the translation,” Gavrilović says. What matters most is not only the style, but the storytelling DNA: “The universal stories of cooperation and the bizarre, non-intuitive solutions for the show’s problems, as well as its lack of actual antagonists in most of the episodes, are what made it narratively unique, and this is what we’re trying to keep.”

That respect extends into method and structure. The team is retaining “the frame-by-frame method of animation, color palette, basic episodic structure, and so on.” Each level is designed as its own miniature cartoon: “We’re making each level as a standalone episode, which (if we removed the minigames and puzzles) could be played as a regular, non-interactive episode of Professor Balthazar… and if we disregard the upgrade to high definition, one might even think it belongs to the old 1960s show.”

The interactivity is built to pause rather than bulldoze the narrative. “The interactivity comes from minigames that pause the story and let players try to tinker with a solution to a puzzle before moving forward,” he explains. Even the genre choice is a philosophical decision: “We decided on a puzzle-adventure genre specifically, since it is the most similar to how actual Balthazar storylines were resolved — through thought and experimentation by the titular character.”

Another element sets the project apart from a typical “reboot”: an intergenerational production pipeline that reconnects the present-day team with Zagreb Film’s legacy. “The younger generation of artists is mentored by people who used to work at Zagreb Film,” Gavrilović says, “so we have a wide range of animators ranging from their early 20s to their late 70s, and everything in between.” The exchange is mutual: “The mentoring actually goes both ways, as the older generation is not versed in using digital tools, and the younger generation can learn a lot from the decades of experience in our greatest and oldest animation studio.”

That connection includes a direct link to the original series. “The project would have been a lot different if we hadn’t found (by sheer luck) some of the people from Zagreb Film, and even one of the original Professor Balthazar animators — Branislav Teslić,” he says. Teslić’s later work includes animation for the short Diary (1974), which was shortlisted for the Oscar in 1975. But Gavrilović’s emphasis is on something harder to credit: studio knowledge. With “almost 60 years” having passed since the pilot, “most of the original team are sadly no longer among us,” he notes, and “had we not connected now, a lot of the ‘internal logic’ of the school of animation… would have been lost to younger generations.”

The revival also exists in a country reshaped by political rupture. Gavrilović is frank about the regional context: “After the breakup of Yugoslavia and the ensuing war in the 1990s, Croatia has formed a bitter resentment toward most of the pre-war cultural and economic successes,” unlike some other post-Yugoslav countries. Yet Balthazar, he says, remains a rare shared affection: “Luckily, Professor Balthazar is generally beloved by everyone and is still aired today on national television.” Because of that, the game does not aim to “address the cultural context of Zagreb Film (a state-owned, Oscar-winning studio in a socialist country outside the Soviet bloc)” so much as to focus on continuity of craft: “the production of new materials that retain the level of quality and style of the original.”

As the Kickstarter date approaches, the studio’s pitch is as much about cultural continuity as it is about a single title. “There hasn’t been a new season of Professor Balthazar since before I was born,” Gavrilović says, “so most young people, even in our country, do not view Balthazar as a ‘living’ brand, but more as a relic of the past.” The goal is to flip that perception—and to argue for a broader way of carrying animation heritage forward. “We want to change this and show that we should revitalize our animation legacy and build on it in new, unexpected areas—perhaps video games, perhaps something else as well,” he says. “Why wouldn’t somebody later make a board game with the theme and visuals of Ersatz, or a collectible card game with Little Flying Bears?”

Most importantly, he positions the project as a bridge rather than a capstone: “The result of this project will be a continuation of the school for new generations, who will then craft something new and exciting on their own. In this regard, Professor Balthazar: The Interactive Season is just a first step of hopefully many more.”

For a character built on empathy and lateral thinking, a puzzle-adventure format may be an unusually natural fit. If the game can preserve even a portion of the original’s gentle weirdness — its faith that problems can be solved by thinking sideways, together—then Professor Balthazar’s magic machine may finally be ready for a new kind of journey.

.png)