Record Profits, Record Output, Record Burnout: Inside Anime’s Quality Crisis

In September 2024, when the highly anticipated adaptation of Junji Ito’s J-horror manga masterpiece Uzumaki (Spiral) premiered on Adult Swim after a five-year production odyssey, its pilot episode was greeted by a rapturous fandom. It was a staggeringly beautiful piece of monochromatic anime that surprised and delighted in equal measure.

What followed is now widely regarded as some of the poorest animation in recent memory. After Episode 1, director Hiroshi Nagahama vanished from the credits entirely, replaced by a revolving door of studios scrambling to finish what Production I.G. USA had started.

Uzumaki wasn’t alone. Fast-forward twelve months, and One Punch Man Season 3’s Episode 6, “Motley Heroes,” earned the ignominious distinction of becoming one of the lowest-rated anime episodes of all time on IMDb, receiving a dismal score of 1.5 out of 10. Blue Lock Season 2’s soccer matches devolved into what fans mockingly dubbed “slideshow animation,” with only the ball moving while players remained frozen. The hit Webtoon adaptation Tower of God Season 2 lost the vibrant visual identity that made its predecessor a 2020 breakout, trading it for drab, lifeless frames.

According to the Association of Japanese Animations’ (AJA) annual survey, 310 anime were produced in 2024 — the highest number ever recorded. That amounts to roughly 6,820 minutes of 2D, hand-drawn animation produced annually by a domestic industry that employs fewer than 6,000 trained animators. This boom is unfolding against the backdrop of production disruptions that began with the COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020. Most anime produced in Japan is broadcast on television, with air dates contractually agreed upon at the committee level before pre-production even begins. Those locked broadcast schedules are colliding with reduced capacity, creating a “crunch” environment that the industry has yet to escape.

THE NUMBERS DON’T LIE

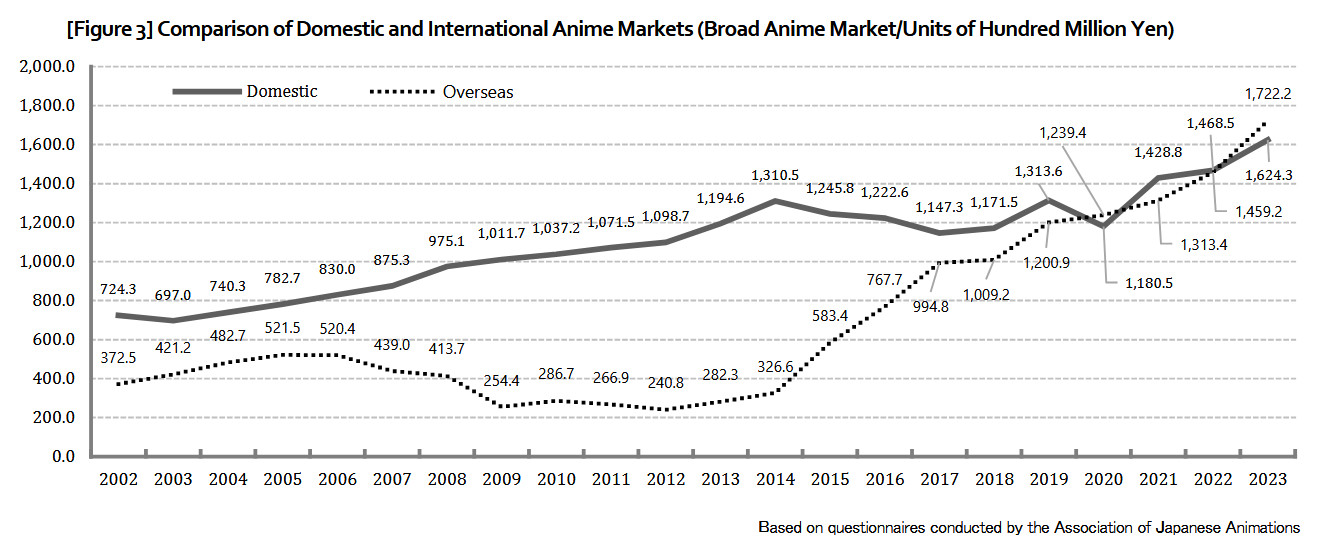

The AJA’s 2024/2025 report, published during TIFFCOM at the end of October, estimates the total market size at approximately $24.9 billion. For the third time in four years, overseas revenue has surpassed domestic revenue, with international markets now accounting for 56% of the total ($13.8 billion).

The catalyst is the collapse of the physical disc market, which has shrunk to just $20.4 million. In its place, global streaming now generates more than $2.36 billion annually. This shift from “luxury boutique” physical sales to high-volume digital utility helps explain why overseas demand now dictates the industry’s survival — and why that demand is outstripping domestic capacity.

Following the collapse of North American home video retail giant Trans World Entertainment between 2009 and 2011, the rise of on-demand streaming — and the legitimization of Crunchyroll — was turbocharged by the 2020–2021 lockdowns. These created a captive global audience and permanently decoupled overseas demand from domestic Japanese trends. By 2024, overseas revenue ($13.8 billion) had surged 26% year-on-year.

This explosive growth prompted the Japanese government to launch its “New Cool Japan Strategy” in June 2024, setting a moonshot target of ¥20 trillion ($127.6 billion) by 2033. The goal, formalized in the Intellectual Property Strategic Program 2024, elevates anime, gaming, and content sectors to basic industry status — effectively reclassifying them from cultural exports to foundational pillars of Japan’s national economy, on par with automotive manufacturing and steel. This designation allows for massive state-backed investment and aggressive legal reforms. Yet beneath these ambitions lie deep, structural challenges.

THE UGLY TRUTH ABOUT LABOR

A common truism among Japanese animators is that nobody enters the industry to get rich — but with revenues at an all-time high, somebody clearly is. The uncomfortable reality is that the industry has remained largely unchanged since its industrial-scale inception in the 1970s and is deeply exploitative. Most animators are not full-time employees and receive no overtime, sick pay, or pensions. Entry-level douga (in-between) animators can earn less than $10,000 per year.

Despite nearly all production houses being fully booked through the end of the decade, many studios remain financially insecure and lack a stable staffing pipeline. The cracks are increasingly visible in the finished product.

In 2024, the United Nations Human Rights Council warned of an “existential threat” to the industry and called for government intervention. In response, a landmark Freelance Law was implemented in November 2024. Established by the Japan Fair Trade Commission, it mandates written contracts, specifies pay terms, and legally restricts businesses from demanding unpaid overtime, while requiring payment within 60 days.

THE PASSION TRAP

A major barrier to reform is what animators call the “passion trap”: the desire to contribute to the medium draws young people into a life of permissive exploitation. Many overwork without compensation for the love of the art. Individual passion for particular manga or light novel IP — or a senior creative’s personal attachment to a project — drives freelancers from one production to the next. They are the industry’s modern-day rōnin: masterless samurai wandering the anime landscape in search of the next worthy assignment.

To break this cycle, organizations such as the Nippon Anime & Film Culture Association (NAFCA) are developing new training certifications and an Animator Skill Test. By standardizing skills and advocating for living-wage entry-level roles, NAFCA aims to professionalize the talent pipeline before the passion trap drains it entirely.

INDUSTRY RESPONSES: OUTSOURCING AND AI

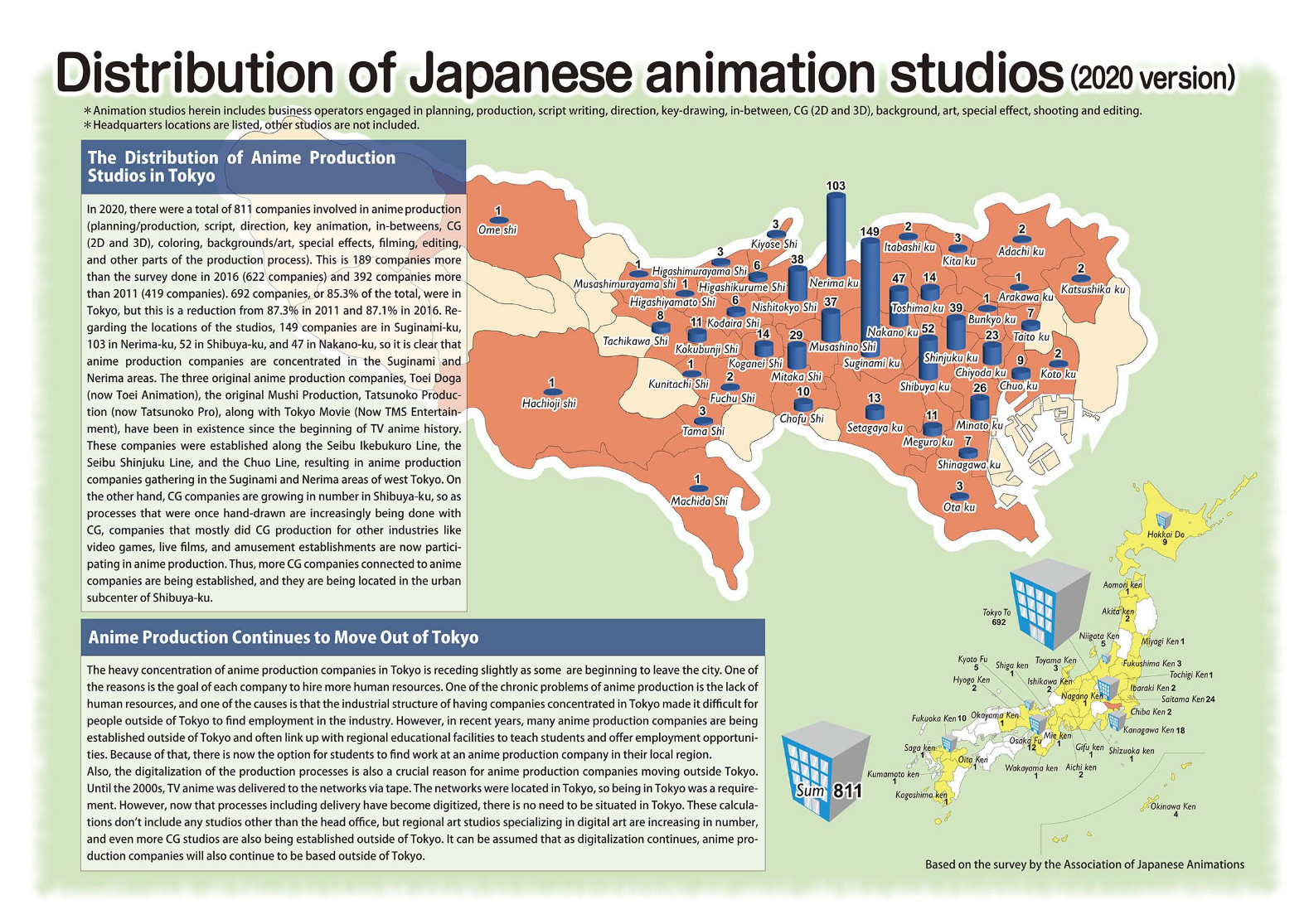

So how are the industry’s biggest players attempting to secure capacity? Toei Animation’s “Vision 2030” commits ¥20 billion ($128 million) to building new studios in Southeast Asia, India, and the Middle East.

The outsourcing narrative is also evolving beyond simple cost-cutting. Data from 2024 shows that 45.2% of surveyed studios outsource part of their production, but the geography is shifting. China has seen a 14.7% reduction due to rising costs, while subcontracting is increasingly moving to Vietnam and the Philippines. Notably, 23.7% of studios now turn to the United States for specialized, high-end digital work. The industry is no longer chasing cheap labor alone, but technical capacity wherever it can be found.

Labor scarcity is also pushing studios toward technology-driven solutions. Dozens of “AI-powered” anime production start-ups have emerged in Japan, though few can yet point to a genuine breakthrough.

Amazon’s 2024 rollout of AI-generated dubbing served as a cautionary tale: immediate fan backlash over its “soulless” delivery forced a rapid retreat. Meanwhile, Toei Animation has committed ¥7 billion ($44.6 million) to AI research and development to streamline workflows. For now, AI remains more of a boardroom promise than a production-floor reality.

By later this year, however, the first wave of Japanese-produced AI tools is expected to emerge with the goal of “sharpening the artist’s brush” rather than replacing the artist altogether. Developers are moving away from general-purpose models in favor of domain-specific AI designed to preserve the aesthetics of hand-drawn animation while addressing labor bottlenecks. These tools are primarily focused on in-betweening, background art, and color scripting.

WHAT MAKES ANIME, ANIME?

Anime’s provenance has long been a key part of its appeal — but does authentic anime need to be 100% Japanese? With 47% of Japanese studios already outsourcing portions of their work, the lines are increasingly blurred. Toei Animation expects that within a decade, 60% of its revenue will come from non-Japanese markets, even as it continues to adapt and produce Japanese IP.

Japan’s anime industry now sits at a crossroads, grappling with demographic decline, rising costs, and insatiable global demand. As production expands into Southeast Asian hubs and AI begins filling gaps left by a shrinking domestic workforce, fears are mounting that the medium risks losing the “hand-drawn soul” that audiences fell in love with. Fan anxiety — reflected in the scathing reception to Uzumaki and One Punch Man — suggests a growing intolerance for visual mediocrity.

If the government and major industry players continue to prioritize the ¥20 trillion moonshot over the physical and creative well-being of artists, Japan may succeed in building a global distribution empire, only to lose the capacity to sustain the quality and artistry that made that empire possible. Whether audiences will accept a “globally manufactured” anime that lacks the distinct Japanese spirit of its forebears may prove to be the defining question of the next decade.

Pictured at top: One Punch Man Season 3

.png)