From ‘Fullmetal Alchemist’ To ‘Chainsaw Man’ And ‘Tatsuki Fujimoto 17 To 26’: Producer Ryo Ohyama On Adapting Manga Across Eras

It’s been a prolific couple of years for manga artist Tatsuki Fujimoto. The continuing sensation of his manga Chainsaw Man carried over into the runaway success of the recent feature film adaptation, Chainsaw Man – The Movie: Reze Arc, which grossed over $174.7 million internationally, placing it among Japan’s top 20 highest-grossing films of all time. The year prior saw the critical acclaim of Look Back, an adaptation by director Kiyotaka Oshiyama of Fujimoto’s one-shot manga of the same name.

And then, in October, came a new adaptation — but this time an anthology of niche stories rather than the artist’s most popular works. That would be Tatsuki Fujimoto 17 to 26, which animates stories from two collections of short manga written and illustrated by Fujimoto from his teens to his mid-20s (as the title states).

17 to 26 shares a producer with Look Back in Ryo Ohyama, who traces the beginnings of the former to production on the latter. He looked at Fujimoto’s Imouto no Ane, which he explains was also a source of inspiration for Fujimoto when writing Look Back. Feeling that this story and the accompanying seven others would fit as a collection, he went on to produce 17 to 26 with Avex Pictures and in collaboration with multiple studios: Zexcs, Lapin Track, Studio Graph, 100studio, Studio Kafka, and P.A. Works.

After a screening of the anthology at the Scotland Loves Anime Festival late last year, we spoke to Ohyama about the making of the series, as well as his work on some of anime’s most famous adaptations, including Bleach, Paradise Kiss, and both versions of Fullmetal Alchemist.

Cartoon Brew: Look Back was quite a small production staff, and this is a much larger project. What was the key to finding balance as you scaled up and worked with these different teams of creators?

Ryo Ohyama: With 17 to 26, the unique appeal is that it showcases the breadth of Fujimoto’s talents and creative works; there are lots of variations. That’s why it made sense to work with seven different studios, to really showcase different approaches and strategies and highlight the breadth of his talent.

Yes, there were challenges, but because this collection of short-form manga was written across a long period of time, Fujimoto’s style itself changed during that span. The way he drew characters was different from story to story, so there wasn’t a strong focus on creating a single cohesive look. Across the eight stories and stylistically different studios, I think the thematic connections in Fujimoto’s work are still evident.

Considering the popularity of Goodbye, Eri and Fire Punch, and the demand for adaptations of those works, what made you want to pick these stories rather than those longer-running series?

I love Goodbye, Eri and Fire Punch, but this goes back to my work on Look Back. These stories were created when Fujimoto was between 17 and 26 years old, when he was younger and really at the beginning of his creative process. There are links not only to Look Back, but also to the story “Nayuta the Prophet,” which connects to Chainsaw Man through both theme and character. There are also many Easter eggs that we weren’t fully aware of at the time.

It’s been such a big year for Fujimoto’s work, with the popularity of Chainsaw Man – The Movie: Reze Arc and Look Back last year. From your perspective, what is the essence of his stories that has made them so popular?

There are many elements, but the one that speaks most strongly to me is the importance of communication. For example, there are characters who are unlikely to encounter one another — humans and mermaids or mermen, aliens and other aliens, or two sisters who struggle to communicate with each other. They overcome those challenges to connect, and I really love that gentleness.

This is also linked to Chainsaw Man, with Denji, who really struggles to open up. That difficulty in trying to communicate with others is something that’s strongly drawn out in that work as well.

Speaking of this being part of Fujimoto’s formative years, I read in a prior interview that he was initially embarrassed by the idea of using his early work. How did he react to the finished version?

I haven’t spoken to him since the completion of 17 to 26, so his reaction is still to come. But yes, he did say that he felt a little embarrassed about revealing what he had written and seeing it turned into animation. He sent a message to all the studios and directors saying that, since we were doing this, they should tap into their own uniqueness and create the work in their own styles. I feel that we achieved that, based on his advice — he really encouraged the individuality of each piece.

Fujimoto didn’t give any input during the animation process for 17 to 26 or Look Back. However, with Look Back, he did mention the musician Haruka Nakamura, whose music he listened to frequently while drawing manga. We approached her to become the film’s composer, since her music had been an inspiration, and we liked it as well.

How did you balance planning across seven different studios?

It was five times more challenging than normal. Each project had its own issues to overcome, but we really hoped audiences would feel a thematic throughline across all of them. Even as we embraced different studios, colors, and sensibilities, we wanted it to feel cohesive.

That was the challenge — finding a smooth joining between projects that weren’t from the same studio or even the same story. When we launched the project in Japan, we invited all seven directors onstage, which is very unusual. Even though it was a single film, it had something of a film festival atmosphere, which made it an interesting task.

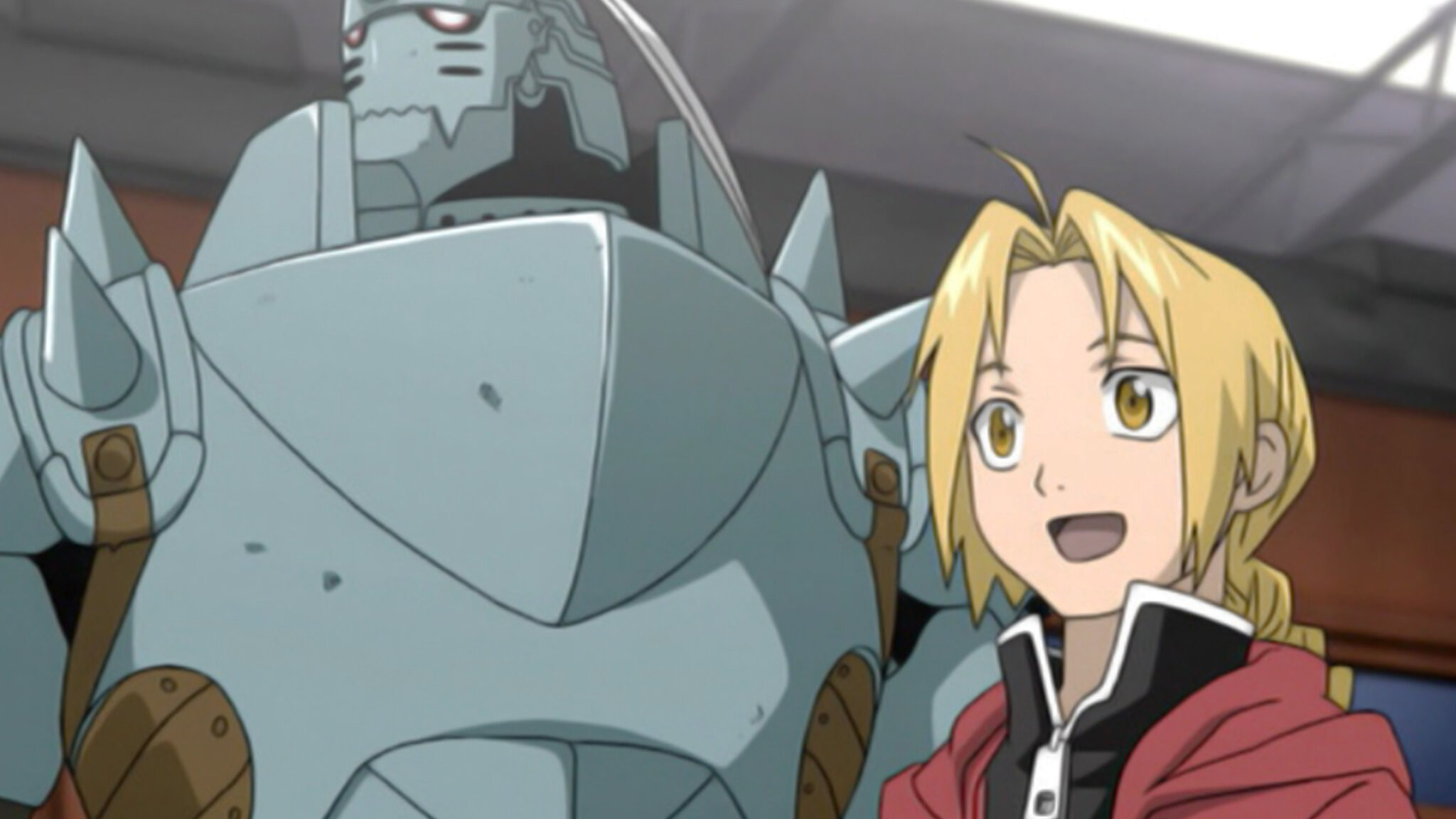

I hope you don’t mind if I ask about your career. One of your earliest projects was the 2003 adaptation of Fullmetal Alchemist. What was that experience like, especially as your debut as a producer?

When the project was assigned, we knew it would run for a full year — about 50 episodes. Based on where the manga was at the time, it was obvious from the beginning that we would need to create original content.

We worked with the production studio Bones in a collaborative process. The lead producer was Masahiko Minami, president and CEO of Bones. He was extremely skilled and assigned director Seiji Mizushima and writer Sho Aikawa, both of whom were capable of creating strong original material. Minami must have known we needed a very strong team.

You also worked on the second adaptation, Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood. Rather than asking why it was remade, what was the goal in making it feel different from the 2003 series?

The first series stayed very loyal to the manga until around episode 25, when Hughes is killed. After that point, the anime diverged more significantly. With Brotherhood, we wanted to honor the original manga, but there were many internal discussions about whether we should start again from the beginning or pick up after Hughes’s death. We also debated whether to reopen with the boys’ failed alchemy.

You worked as a music producer on Bleach and Eureka Seven, and as a sound producer on Honey & Clover. Can you talk about those roles?

In those three works, my role was primarily as a music producer, because there was a separate overall producer. In many other projects, including Look Back, I take on both roles. With Bleach, Eureka Seven, and Honey & Clover, this was partly because I belonged to Sony Music at the time, so the music producer role was assigned to me. If I were approached specifically as a music producer again, I would definitely consider it.

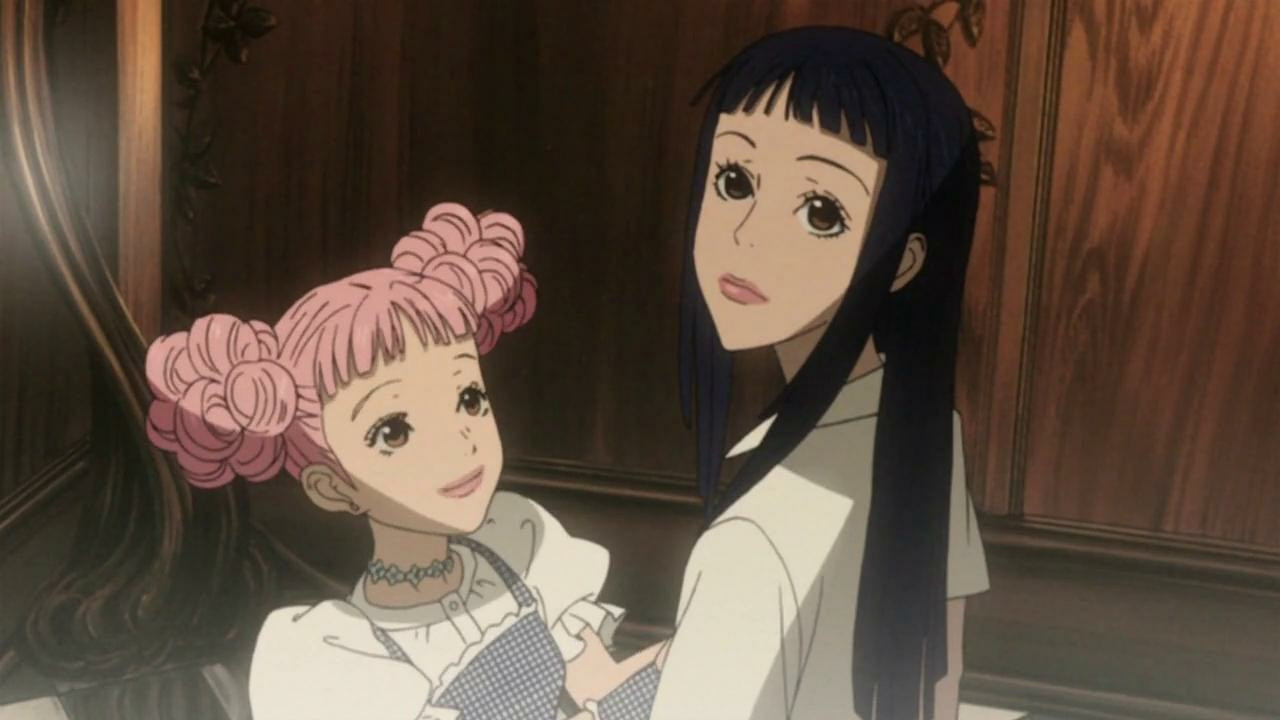

Most of your adaptation work has been under the umbrella of shonen manga, but you’ve also been involved in adaptations of Ai Yazawa’s work, including Paradise Kiss. Given the different audiences, what changes behind the scenes?

It’s completely different. You’re right to point out the different audiences. For example, Fuji Television has a programming slot called Noitamina, which targets what’s referred to in Japanese marketing as the F1 demographic — women aged 20 to 40. Noitamina was created specifically for that audience, and Honey & Clover was the first anime to fill that slot. At the time, Sony Music was the sponsor, and I was heavily involved as a producer.

Given your role in music production, and since we’re in Scotland, I wanted to ask about one of my favorite ending themes: “Do You Want To” by Franz Ferdinand in Paradise Kiss. How did that come about?

For Paradise Kiss, we were initially looking for an artist from the Sony Music label, so the discussion was open-ended. There was also an artist management producer on the project. We wanted someone who wasn’t Japanese — an internationally known, well-established artist. The suggestion to go with Franz Ferdinand came from that producer, and it became an interesting challenge.

.png)