How The Hays Code Censored Cartoons And How Animators Responded

We’re living in a strange era of Hollywood self-censorship right now. With physical media dying out and streaming services becoming the default method of watching films, sites like Disney+ are free to scrub out “objectionable” material like Elisabeth Shue’s F-bomb in Adventures in Babysitting and Daryl Hannah’s posterior in Splash, and the censored cut becomes the only cut available.

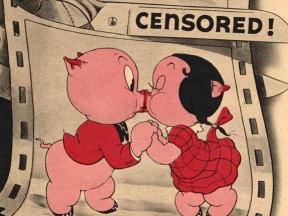

What some people may not be aware of is that there was an earlier attempt at Hollywood self-regulation in the form of the Motion Picture Production Code, popularly known as the Hays Code (named after its founder Will Hays). The Hays Code had strict rules regarding language, sex, nudity, and violence, and Hollywood films of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s had to gain a certificate of approval in order to be released. These rules applied to animated cartoons, which were targeted largely toward adult audiences at the time, as well as live-action features, and the Hays Code is directly referenced in this great gag from the Warner Bros. cartoon A Tale of Two Kitties (1942).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

With the explosion of talkies in the late 1920s, movie studios looked to talent from the New York stage to write dialogue and musical numbers. Studios quickly found that the salaciousness typical of Broadway wouldn’t fly in other parts of the country. The Catholic Church was calling for a purification of cinema, and the movies faced potential boycotts and edits from local censor boards. In the hopes of preventing government intervention, which would be completely out of the studios’ control, film executives enlisted Presbyterian elder Will Hays to create a set of rules for the silver screen. Hays himself, featured in the clip below, was caricatured in the Mickey Mouse cartoon Mickey’s Gala Premier (1934), which pokes fun at his rule over Hollywood by putting him in a crown and kingly robes.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Hays created the code, but it was Catholic journalist Joseph Breen who was the chief censor, and filmmakers had to adhere to his suggestions whether they liked it or not. Here’s Breen talking about the necessity of the code.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

The Hays Code was created in February 1930, but it wasn’t strictly enforced until July 1st, 1934. Cartoons of the 1930-1934 period, known as the Pre-Code Era, were teeming with soon-to-be verboten elements, especially the ones by Ub Iwerks (co-creator of Mickey Mouse). Ub Iwerks’ Flip the Frog cartoons of the early 1930s contain language that would be banned only a few years later.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

This moment from the Iwerks cartoon Spite Flight (1933) would never have made it to the screen a year later due to this code rule: “Obscenity should not be suggested by gesture, manner, etc.”

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

And this bit from Iwerks’ The Office Boy (1932) would have run into trouble a few years down the line thanks to the code’s commandment: “Dances which emphasize indecent movements are to be regarded as obscene.”

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

This scene from Iwerks’ Room Runners (1932) would definitely have been axed under the code’s rule: “Nudity is never permitted.”

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Also, let’s not forget the opium sequence in Iwerks’ A Chinaman’s Chance (1932), a violation of the code’s decree: “Illegal drug traffic must never be presented.”

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Many of these rules were fairly silly (married couples couldn’t sleep in the same bed), while others may have impeded social progress (the code prohibited “sex relationships between the white and black races”). The code flatly forbade portrayals of gay characters, who popped up in a number of pre-Code cartoons. These depictions are predictably stereotypical by today’s standards, but it’s interesting that they exist at all, considering that homosexuality went unacknowledged in Hollywood for the next several decades. Here’s a very gay scene from a Thunderbean print of the Van Beuren short Marching Along (1933).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

The cartoon character hit hardest by the Hays Code was Betty Boop, whose films mixed risqué innuendos with absurdist imagination. The incredible Max Fleischer cartoon The Old Man of the Mountain (1933), which features music and vocals from jazz legend Cab Calloway, is one of Betty’s best. (Note that “kicking the gong” was a slang term for smoking opium.)

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

The Betty Boop cartoons were enormously popular, but the short Red Hot Mamma (1934), in which Betty visits the fiery pit of Hell, did stir up some controversy. The short was banned by the British Board of Film Classification for its comical depiction of the netherworld, and several theater exhibitors wrote in to the Motion Picture Herald to complain. One wrote, “All Betty Boop cartoons have been good up to this one, but when an exhibitor books in a cartoon to show to children and have the music blare forth at the kids with ‘Hell’s Bells,’ and a trip to the lower regions, it is time to raise a kick (which won’t do any good).” Another exhibitor wrote that “the cartoon Red Hot Mama [sic] must have been drawn while the guy was drunk,” and added, “The only recommendation I have for this is that the one responsible for it be compelled to sit through a screening of this every time he has a pink elephant fantasy.”

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

When Breen was put in charge of the code in 1934, one of his first acts was to muzzle poor Betty Boop. The Fleischer shorts weren’t as bawdy as the Iwerks cartoons, but I’m guessing Betty was targeted for the same reason the code came down so hard on promiscuous comedian Mae West: Betty is openly flirtatious and the audience is invited to like her for it. As the code stated, “Sexual immorality is sometimes necessary for the plot,” but such impurities “must not be made to seem right and permissible.” There are no shortage of films from before and during the code where loose women receive their comeuppance, but Betty is constantly winning car races, science fairs, and even presidential elections. Furthermore, the other characters in these shorts all adore Betty, as you can see in this sweet scene from Betty Boop’s Birthday Party (1933).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Breen deemed Betty’s winking and hip-swiveling to be “suggestive of immorality,” and the series had to be revamped. So in 1934, Betty’s skirt was lengthened, her canine boyfriend Bimbo was dropped, and her surreal adventures ended. Many of the animators responsible for Betty’s pre-Code antics – Roland Crandall, Willard Bowsky, Seymour Kneitel – were moved over to the Popeye series, while Betty was handed off to Myron Waldman, who later helmed the Casper the Friendly Ghost series. Waldman was a talented artist, but he favored cuteness over weirdness. Several Code-era entries are fun, but Betty herself is disappointingly domesticated, as seen here in Baby Be Good (1935).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

To be fair, the Code probably just helped to push along a trend that was already developing. Disney’s lavish Silly Symphonies were leading the industry in the mid-1930s, and other studios abandoned the anything-goes strangeness of early 1930s cartoons in favor of innocent fairy tales. Compare the loopy insanity of Hell’s Heels, a Walter Lantz cartoon from 1930, to the juvenile (but still very charming!) Jolly Little Elves, a Lantz cartoon from 1934.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Even with Breen breathing down their necks, animators of the 1940s and 1950s were constantly slipping dirty jokes in their films; they just had to be a little more subtle than Iwerks had been. In the Chuck Jones cartoon Wild About Hurry (1959), Wile E. Coyote is given a bogus Latin name that references the mythical Greek king Oedipus, who married his own mother, leaving a certain profane term implied (it’s a perfect description of Wile E., too).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

The limitations imposed by the Code were often used as a source of humor, as in this great bit from Tex Avery’s The Shooting of Dan McGoo (1945).

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Cartoons of the Hays Code era seemed to get away with more than live-action movies of the same period (rules related to violence and respecting the law were never adhered to even slightly in cartoons). Avery had a trick for circumventing censorship: he would toss in a few blatantly inappropriate gags for the censors to snip out so they wouldn’t pay attention to the racy material he really wanted in there. The now-lost original ending of the classic Red Hot Riding Hood (1943) forced the wolf into marriage with the grandmother, resulting in three wolf children. The Code cried bestiality and had it changed, but perhaps it allowed Avery to get away with the lusty gags that fill up the rest of the short.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Looney Tunes director Bob Clampett also used this trick, telling Michael Barrier, “If I wanted to be sure that certain things were left in, I’d put in a few extra ‘goodies’ just for the censors. They’d cut those, and leave in the ones I wanted.” In the case of An Itch in Time (1943), Clampett inserted this kinky line as censor-bait, but they didn’t catch it and left it in!

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Dancing around the censors didn’t always work: Avery’s The Crackpot Quail (1941) was originally supposed to have the quail repeatedly blowing raspberries, but the Hays Office apparently found this to be vulgar and had it changed to an irritating whistle. Amazingly, the original print still exists and was finally made available on the Tex Avery Screwball Classics volume 3 Blu-Ray set. The original version is much, much funnier. A sample:

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Another long-lost Looney Tunes scene, which only just resurfaced in 2022, directly ridicules the Hays Code. The joke, from Bob Clampett’s Farm Frolics (1941), seems like a dig at the Code for censoring the spitting noise in The Crackpot Quail. In a similar joke from the Warner Bros. cartoon Hop, Skip and a Chump (1942), a character spits offscreen and remarks, “Expectorating is censored, ya know.”

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Another interesting trivia item: the Hays Code is the reason why Tweety Bird is yellow. He was pink in his first three cartoons, but when the cat from A Gruesome Twosome (1945) referred to Tweety as “the naked genius” (the title of a 1943 Broadway play), the censors realized Tweety was nude and insisted he be covered in feathers for future appearances.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Most of the material cut by the Production Code Administration hasn’t survived, although we know about some of it. Clean Pastures was edited for burlesquing religion, and Hollywood Steps Out was originally going to end with a caricature of Clark Gable kissing Groucho Marx in drag (Gable would then declare, “I’m a bad boy!”). As a kid, I was confused by the abrupt ending of the Daffy Duck cartoon The Stupid Cupid (1944). Apparently, after Daffy’s wedges himself into a three-way make-out session, he was supposed to remark to the audience, “If you haven’t tried it, don’t knock it!”

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Sadly, most of these deleted scenes are lost to time. I’ve always wondered about this jarring cut in Frank Tashlin’s Hare Remover (1946). Maybe someday the lost scene will surface and we’ll find out why Elmer looks so annoyed…

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

After Breen’s retirement in 1954, application of the Code became less draconian. When the cross-dressing comedy Some Like it Hot (1959) was released without a seal of approval to tremendous success, the Code’s stranglehold on the industry weakened. After years of lackluster enforcement, it was officially abandoned in 1968 and replaced with the MPAA film ratings system.

Ralph Bakshi’s X-rated 1972 movie Fritz the Cat is often credited as the first “adult” animated film, but as you can see, cartoonists were constantly pushing the envelope before and even during the Hays Code era. To finish things off, here’s one deleted scene that still survives: the original ending of the Bugs Bunny cartoon Hare Ribbin’ (1944), which the Code nixed. Murder was typically allowed in cartoons, but this gag apparently went too far. As the Russian canine in this short might say, censorship shouldn’t even happen to a dog.

— Cartoon Study (@CartoonStudy) February 16, 2023

Some of the restorations featured here are by Steve Stanchfield at Thunderbean Animation, maxfleischercartoons.com, and Warner Archive. Thanks to Thad Komorowski, David Gerstein, and Jerico Dvorak for the Farm Frolics clip.

.png)