Maïlys Vallade And Liane-Cho Han On Their Thought-Provoking Hand-Drawn Feature ‘Little Amélie’

French co-directors Liane-Cho Han and Maïlys Vallade have a background in storyboarding. They met working on The Little Prince (2015) and found their sensibilities and sensitivities to be a good match. When Vallade was called on to work on Rémi Chayé’s 2015 feature Long Way North, which won the audience award at Annecy, she brought Han on board with her and Han also became the film’s animation supervisor. The duo collaborated again with Chayé on his 2020 feature Calamity, a Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary.

Working with a team of likeminded artists that they encountered working on these projects — including concept artist Eddine Noël and Rémi Chayé, who contributes here as a background artist – Han and Vallade have now crafted their feature-length directorial debut: Little Amélie (Amélie et la Métaphysique des tubes). The film premiered at this year’s Cannes Film Festival as a special screening, and is playing this week in competition at the Annecy Festival.

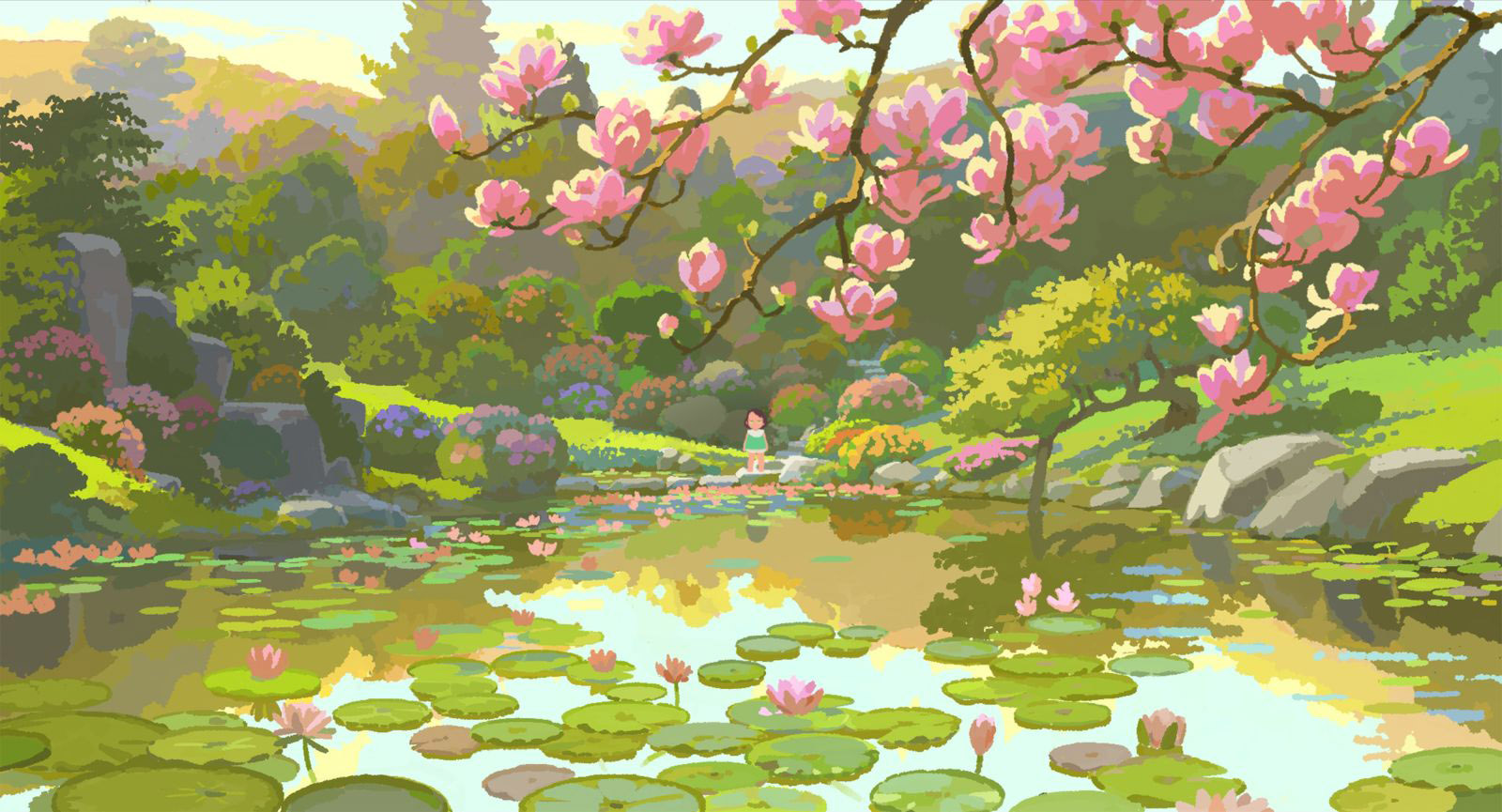

A fascinatingly fluid animation, Little Amélie’s bright pastel palette stood out in the Cannes program, as did its uniquely transnational premise. The film charts the identity formation and reformation of the eponymous Amélie, a young Belgian girl growing up in Japan in the late 1960s who believes she has a special connection with God. Her everyday life straddles the two cultures: her home is a traditional Japanese house, but it’s adorned with anachronistically Belgian furniture. Her family members are Belgian, but it’s her Japanese nanny, Nishio-san, that she enjoys spending time with the most. But these halcyon days can’t last forever, and Amélie finds herself confronted with harsh truths about who she is and who she isn’t. Adapted from Amélie Nothomb’s semi-autobiographical short novel Metaphysique des tubes (2000), the film is co-produced by Maybe Movies and Ikki Films.

Following the film’s premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, Cartoon Brew sat down with Han and Vallade to discuss their creative inspirations and impulses, their approach to capturing a child’s perspective on the world, and what makes the film’s cultural cocktail unique.

Cartoon Brew: What was the genesis of this project, and how did you come to partner on it?

Liane-Cho Han: I read the book when I was nineteen. At that time, I wasn’t a big fan of literature. I come from pop culture – Japanese animation, video games. But when I read this book, I really fell in love with it. This is a story of a two-and-a-half year old girl and her relationship with Nishio-san in Japan. I already had the fantasy to adapt it, but I was just a young student – I didn’t believe I would. A lot of years passed, until I had my first child. I realized that, no, it’s not just that this character believes this, all children do at this age. It made me feel okay to try again at adapting it. I wrote a letter to the book’s author, and I bought a copy of the book and offered it right away to my niece.

Mailys Vallade: We’re both storyboarders. We worked together on The Little Prince. I was called by Rémi Chayé to work on a project called Long Way North. I felt that Liane-Cho’s sensitivity was very close to that of the project, so he joined. Then we worked together on a project called Calamity. We had this strong immersion in character-building, and we also participated in the writing process. We built this creative family, joined by Eddine Noel, who became our art director. All this family building allowed Liane-Cho to say that maybe it was time, and we felt able to adapt this story.

What made you feel that the novel had potential in animated form?

Han: I really believed that the only way to adapt this book would be animation, because there’s the potential to be more crazy. And it’s super difficult to find a two-and-a-half-year-old actress to act in that role. [Animation] could give us so much freedom to illustrate all the fantasy and magic that this little girl has in her mind.

Vallade: We realized that it was important not only to have her perception and gaze, but also her gaze on childhood. The book is full of literary descriptions that we had to transform into visual ideas – we couldn’t just do them literally. It was crucial to have that voiceover hand-in-hand with her gaze – to see through her eyes – so that we could picture and depict her fantasies, and how she transfigures the world in a dream-like style. Only animation, in our opinion, could do that.

Han: We positioned the ‘camera’ to be at her level, her height, throughout the movie. You see what she sees with her eyes, which allowed us to play with the scale of things.

Did the novel resonate with you personally or culturally?

Vallade: It doesn’t resonate with me culturally, but more emotionally, this connection to an ideal or idea that you have about life. Of course, for Amélie, it’s that her identity is built on being Japanese, but the story could have happened elsewhere. The important thing is that she had found this identity that she had idealized. It’s like any other child in life, who thinks that they are able to do something, and then they realize that they can’t, and that things aren’t as they imagined them to be, and that things evolve, which can be a good thing.

Han: Personally and, of course, culturally. I’m French, but with Chinese origins – I have both cultures. So, of course, this mix of two cultures in the book resonated with me emotionally. I really felt for this illusion that she has. She realizes that she’s not Japanese, and I felt a lot of emotions. In the book, there’s nothing. On the contrary, in the movie, we wanted to give a more positive perspective to the kids who are going to watch it.

The novel and your film span multiple cultures — how did that influence the look and feel of the film? I sense influence from Japanese animation here, and also perhaps French and American animation.

Vallade: Yes, our influence is very Japanese. The way the story is built, the way the characters are built, and these stories about growth. We used to watch a lot of Dragon Ball and similar shows when we were young – so it’s part of our DNA. We tend to mention [Isao] Takahata and [Hayao] Miyazaki, mainly because we love them, and of course because our work reminds people of them. They have this poetic dimension, and we are very much in that vein. We wanted a sensory, poetic, childlike story, to bring the viewer on board, but through a realistic approach.

Han: We are also very inspired by live-action movies. One of our biggest goals is for people to forget that they’re watching an animated movie – that we are not watching drawings, we are watching humans perform and experience emotions.

Tell me about the film’s aesthetic. Your characters lack outlines, and you’ve opted for a pastel color palette.

Vallade: Our team had worked with this style and look before. The outlines are like that because we don’t want to box in our characters. We have this soft, round, but very textured and warm outline that’s in keeping with the backgrounds. In this way, we’re close to live-action, although we have those flat areas with colors that are simplified. We wanted to continue with this process having already experienced it on Calamity.

Work with color and light was crucial. We worked with the change of seasons, and so went from pastel colors to acid colors. We’re tackling heavy, tough themes, and we wanted her perception to transcend them.

Han: And of course, there’s a big advantage to not having outlines around the character as in a traditional film. When you see the light hit the character, it creates so much atmosphere. There is no order, and it integrates the character, merging them with the background almost like a painting. It adds to this poetic feeling.

Is the film animated by hand or are there cg elements?

Vallade: By hand, digitally.

Han: Eddine Noel was the architect of the traditional Japanese house in the film. We made a 3d model of the whole house – all the rooms, all the interiors.

Vallade: We used it for staging characters and layering backgrounds, but it’s not there in the final image.

Han: It’s just there to have a basic perspective, so that you don’t have to think too much. We see from Amelie’s perspective in the house, and it’s a difficult perspective to draw. So it’s to have this camera in a good place, and to have her point of view, and all the possibilities with 3d.

Your creative team is for the most part non-Japanese, and you’re working with a mise-en-scene that’s outside of your own cultural experience. There are of course clichés that you want to avoid as an outsider representing Japan…

Vallade: Eddine Noël did some incredible photographic work. We wanted to explore Amelie’s idealized Japan, but also to get back to the reality in Japan, interpreted through our impressionist take. We had a lot of documentation – photos, pictures of where Amélie Nothomb grew up in the Kansai region. We went far in our recreation of a traditional Japanese house. Her actual house was demolished, so we didn’t have that. There’s Belgian furniture inside of it, from those expats. It’s how these cultures are confronted with each other, and how they merge into this chamber play going on in the house. There was a lot of research, even down to details like the vacuum, refrigerator, and the vegetation and fauna that could be inside a garden at that time in that region. The iconography that we used was close to a fairytale, because it helps to bring existential and philosophical questions. And there was something of a theater-like staging. Those were the directions that we wanted to go in.

What do you hope that this film gifts audiences? What do you hope they take away from it?

Vallade: The importance of reconnecting with this innocent gaze, and to remember as grown-ups that it may be key in your adult life to keep this empathy towards what you see in the world. We also want to give a positive spin on her idealistic conception, that that tragic moment in her life can be transformed in another way. There is always possibility and hope – a way out.

Han: It’s okay to lose something because there is so much promise. It’s different. That’s what we want. It’s positive to embrace the future.

.png)