‘How Do You Turn A Weakness Into A Strength?’: ‘GOAT’ Director Tyree Dillihay On The Meta Message Behind Sony’s Hit Underdog Story

Sony Pictures Animation’s original feature GOAT is the first animation hit of 2026, earning $47.6 million worldwide over its opening four-day weekend and securing the studio’s only CinemaScore A rating.

GOAT was animated by Sony Pictures Imageworks and is a rare original Sony Pictures Animation release to receive a theatrical rollout in recent years, as other productions like KPop Demon Hunters and Fixed went straight to Netflix as part of an exclusive streaming distribution deal. The gamble to go theatrical paid off with the relatable story of a tiny “roarball” obsessed goat named Will Harris, voiced by Caleb McLaughlin, who is desperate to get a chance to go pro among much bigger, scarier animal peers who do not think he has the height or talent to dominate the court.

The film marks the feature directorial debut of Tyree Dillihay, who started as an animator in 2006 on MTV’s Where My Dogs At?, then went on to storyboard for projects ranging from Pink Panther and Pals to Bob’s Burgers and The Venture Bros. At Bob’s Burgers, he moved into episodic animation directing and further refined those skills on Good Times and Weather Hunters.

With GOAT, Dillihay and fellow sports fan and co-director Adam Rosette teamed with producer and NBA legend Stephen Curry to make an animated sports movie that delivers the stakes and kinetic energy of a live game while also standing out from other films centered on anthropomorphized animals. The film is ambitious in its sports cinematography and in its construction of ecologically distinct realms that host the roarball games.

Cartoon Brew recently caught up with Dillihay following GOAT’s release to discuss the design and camera work inspirations that make the film feel modern and distinctive within feature animation.

Cartoon Brew: To Sony Pictures Animation’s credit, their feature films have been visually diverse. As you pointed out in a recent interview, they do not have a house style, which means there is a blank canvas when beginning GOAT. What was your process in deciding where to start first, environments or characters?

Tyree Dillihay: Personally, I am style agnostic. I am a chameleon and shift artistic styles and perspectives to fit the project I am working on. I feel that the style serves the story. For GOAT in particular, the big-picture question was how to put animals in a familiar yet unfamiliar setting, in a world that looks like it was built by them for them. But you cannot go too alien, or there will be a disconnect and low buy-in from the audience.

With that in mind, the order of operations was always story, and character and world building happened somewhat simultaneously at the beginning. The reason is that when you start with your lead, you have a small animal, and the world needs to be subtly oppressive.

Will is very small when we meet him, living in a room in a garage surrounded by gerbils. Everyone around him just keeps getting bigger and more imposing.

Yes, it is very intentional. Where does he live? It is not even an apartment, it is a garage, and it is a gerbil’s garage. We were always reinforcing that Will is “small” in a world that is not built for him.

Then we move into the larger world outside that garage, starting with Vineland. Where is his home? Vineland is what we like to call a jungle within a city.

It looks like a favela reclaimed by nature.

Yes, we like to say it is Brazil mixed with Brooklyn. How do we juxtapose those two things while still retaining the urban quality of Brooklyn? You have a bodega around the corner, a movie house, a train station, and the local stadium. Even the street asphalt is broken down, but it is filled with colorful grout, mosaic tiles, and street art you might find in São Paulo. At the same time, the jungle canopy blocks out sunlight in some areas. It is subtle, but it creates a slightly oppressive environment.

If you notice, over the course of the story, the movie gradually gets brighter. By the end, it is a new day.

When we move into the other worlds, starting with the sport itself, we always said we wanted to make it an international game. The NBA is domestic. We wanted a global game to expand the league and our cinematic potential to explore more worlds. Initially, we called them regions, but the idea was that when you visit these other places or biomes, they are worlds apart.

When you found your animals, did you create the biomes around them, or did the biomes exist to support your species of players?

It is funny. The short answer is that players are not native to the teams they play on. We literally chose them by size. We wanted the largest apex predators to populate the league. When Will joins the Thorns and becomes a professional roarball player, he is a fish out of water, the odd goat out.

Early on, we thought that if they were in the Arctic, it should all be Arctic animals. But then the biggest animal there is a polar bear, and that is it. Instead, we have a polar bear, a snow leopard, and a saber-toothed tiger. We relegated penguins to referees because it was funny, even though we did not treat them in a wacky way.

We had to think very carefully about these decisions because we did not want to take the audience out of the story. We wanted them to believe this is a real sport with real stakes.

The film has a visual aside called “Goat Vision,” when Will enters a heightened perceptual zone. How did that come about?

The biggest challenge was making sure it did not feel like a superpower. Otherwise, the audience would ask why he does not just use it all the time. It was always part of the story, but we had to walk a tight line to show that it was an ability he had not fully honed yet.

He has an innate way of seeing the world differently from other animals, but under pressure, how do you perform? How do you turn what is perceived as a weakness into a strength? That was the story calculus we needed to solve for it to pay off effectively.

The backgrounds have a watercolor, impressionistic aesthetic, while characters and key objects use more defined edges. Was that discovered during development or intentional from the start?

It was a very early decision. Credit goes to production designer Jang Lee and art director Richard Daskas for helping craft that impressionistic style. We are big fans of artists like John Singer Sargent, Cézanne, Nicolai Fechin, and the late Richard Schmid.

These painters balance loose and tight brushwork, hard edges and soft edges, and atmospheric perspective. It felt like the best artistic approach for showcasing world-building. The detail is concentrated in the animals’ fur, while the clothing and environments are more painterly. We make very intentional decisions about where the eye should focus and what should remain subordinate.

You also incorporate modern sports photography into the cinematography. Did you study specific references to achieve that look?

We worked closely with our head of cinematography, John Clark, exploring lenses and depth of field to emulate sports photography, live gameplay, and broadcast coverage. We also looked at lo-fi third-person phone footage and how that reads visually.

Honestly, there was not a formal study. Adam Rosette and I are big sports fans. We watch this stuff every day, so it comes naturally. It was more about sharing references quickly and educating parts of the team who do not watch sports, helping them understand the visual language of modern sports coverage.

We also talked about how Space Jam came out 30 years ago. It was great for its time, as was the newer version, but we wanted a fully animated underdog sports film that meets a new generation where they are, using modern storytelling and visual language. I think we accomplished that.

Did Unreal Engine replace storyboarding in any way during development?

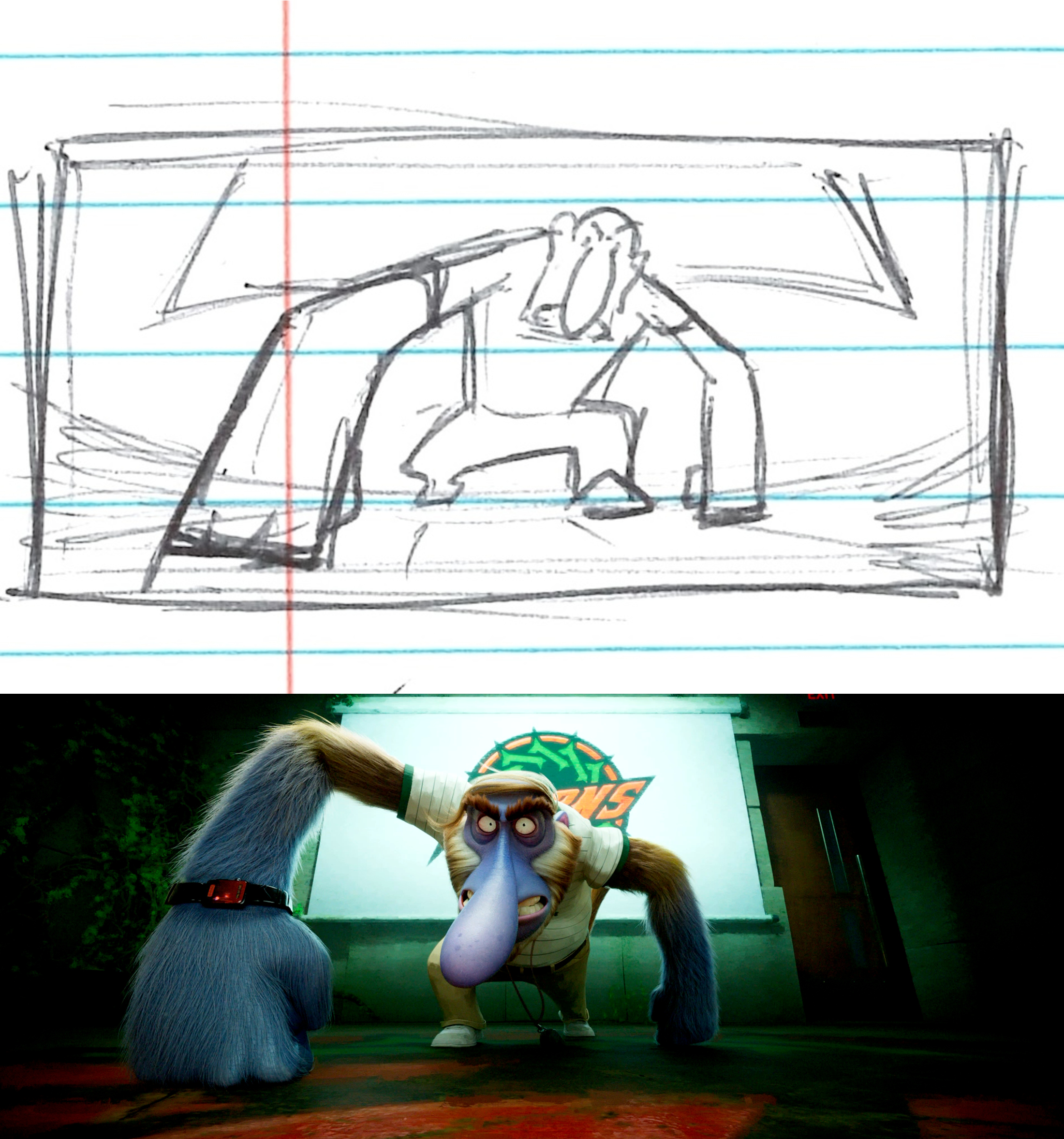

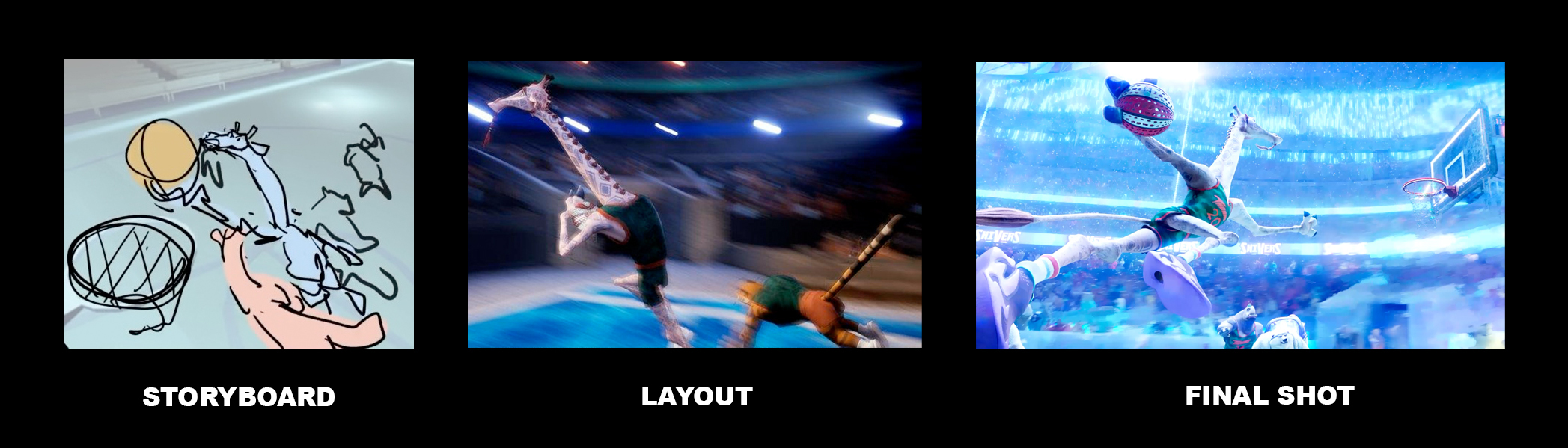

No, the process still starts with storyboards. Storyboards are the ultimate stress test for animation. You can quickly see what works and what does not.

Some story artists worked traditionally with sketches sent to editorial. Others incorporated 3D tools to explore camera movement, though not Unreal specifically. We encouraged that flexibility. Story artists are essentially assistant directors. They control the camera and explore how we shoot scenes.

Once we moved into layout, storyboards became a starting point, but we gained more freedom. We were not beholden to them shot for shot. Unreal allowed Adam and me to work like live-action directors, virtually walking the set and blocking shots. We could generate 15 different camera versions per setup and then assemble the best sequence in editorial.

Was there a sequence that required the most production runway?

Yes, two sequences: the semifinal game between the Thorns and the Shivers, and the final game between the Thorns and the Magma. The final game, in particular, required editing, storyboarding, layout, and animation working in concert.

Originally, the final game was 14 to 15 minutes long, and we had to condense it so audiences would not glaze over. Finding the right shots to deliver the emotional arc and world stakes inside a live volcano was essential. That final moment is the hero’s journey.

Cutting that much material is incredibly challenging.

Huge credit goes to our story team, including head of story Keely Propp, Stephen Walker, and Felix Yang. Stephen handled a large portion of that sequence, and I am glad he survived it. At the wrap party, he told me how amazing it turned out, and I thanked him for the boards. It is a testament to the process. Some might call it old school, but nothing replaces strong storyboards. If it was good enough for Alfred Hitchcock, it is good enough for me.

Looking back on your first feature, what made working with Sony Pictures Animation a positive experience?

I cannot compare it to other studios, since this was my first feature, but Sony respects unique storytellers. KPop Demon Hunters is culturally specific yet universally accessible. The same is true of GOAT. It has a specific voice, but it resonates broadly.

That kind of risk-taking and respect for the process is essential. It is how we find new voices and tell original stories. You have to go to new wellsprings of talent and let them cook.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

.png)