Commentary: It’s Not Just The Beginning – Animation Has Always Pushed Boundaries

Where to begin with that narcissist foul-up called the Oscars?

First, we had the Academy’s decision not to televise a bunch of categories, including the award for best animated short. Then, during the Oscars, three “Disney” actresses came on to announce the animated feature winner. First, they did their Disney duty by plugging their past and future Disney film roles (all this happening on a Disney-owned network). Then, these three animation historians went on to tell the world how animation is first and foremost a kid’s thing. All this before eventually announcing the winner, which, what a surprise, turned out to be a Disney film.

But, those issues have already been discussed here.

One moment that might have slipped past people were the comments made by Alberto Mielgo after winning the short animation Oscar for The Windshield Wiper.

Now it didn’t start too bad. You can’t quarrel with Mielgo’s opening remarks that rightly claimed animation includes every art form and that “adult animation is a fact.” It was his closing line that rankled me: “This is just the beginning of what we can do with animation.”

I really got the impression that he thinks he’s somehow radically reinventing animation and that adult-oriented animation did not exist before. I have nothing against Mielgo. I don’t think he was doing anything malicious, but it was a naïve and incorrect comment. (In a separate interview I did with Oscar nominees for a different publication, he talked about how being nominated showed that the Academy was finally taking adult animation seriously, which is just not true.)

Let’s be clear: This is NOT the beginning of what can be done with animation. That’s been happening for decades, maybe centuries. It’s always happening.

How do I know?

Well, a little background.

I’ve been involved in animation for 30 years as a writer, author, and as the artistic director of the Ottawa International Animation Festival (OIAF). My job (unbelievably) is essentially to watch over 2,000 animation films (of all shapes and sizes) annually and select the best ones for festival programs. In short, I see a lot of animation.

During this time, I’ve made it a priority to find innovative voices. I was always bothered by the way animation festivals (including the OIAF) tended to prioritize films for how they looked rather than what they had to say. Too often, I saw films that were beautifully crafted but had (in my view) absolutely nothing interesting or unique to say. I tried (and still try) to shift away from craft and technique and prioritize what a film is saying. A great example might be JJ Villard’s now classic student film, Son of Satan. It’s an ugly film with distorted audio, but behind that was a potent punk riff about bullying and domestic abuse. There was an urgency to that film that is too often missing in animation. In short, I’ve done my best to seek out and share unsung and overlooked voices – and there were and are plenty.

So when I hear someone talk as though animation was somehow never mature, relevant, or provocative until now, well, yeah, I take issue.

First off, all you need to do is glance over at some of Mielgo’s fellow nominees: Bestia (about a torturer), Affairs of the Art (about a dysfunctional family), Boxballet (about a love affair between a boxer and a ballerina that maybe touches upon some issues of gender stereotypes). Aside from Robin, Robin, all the nominees were aimed at adult audiences. And as problematic as Oscar selections are (they do not accurately reflect the state and quality of the animation world), adult or art-house animation has always had some place (however small) at the Oscars.

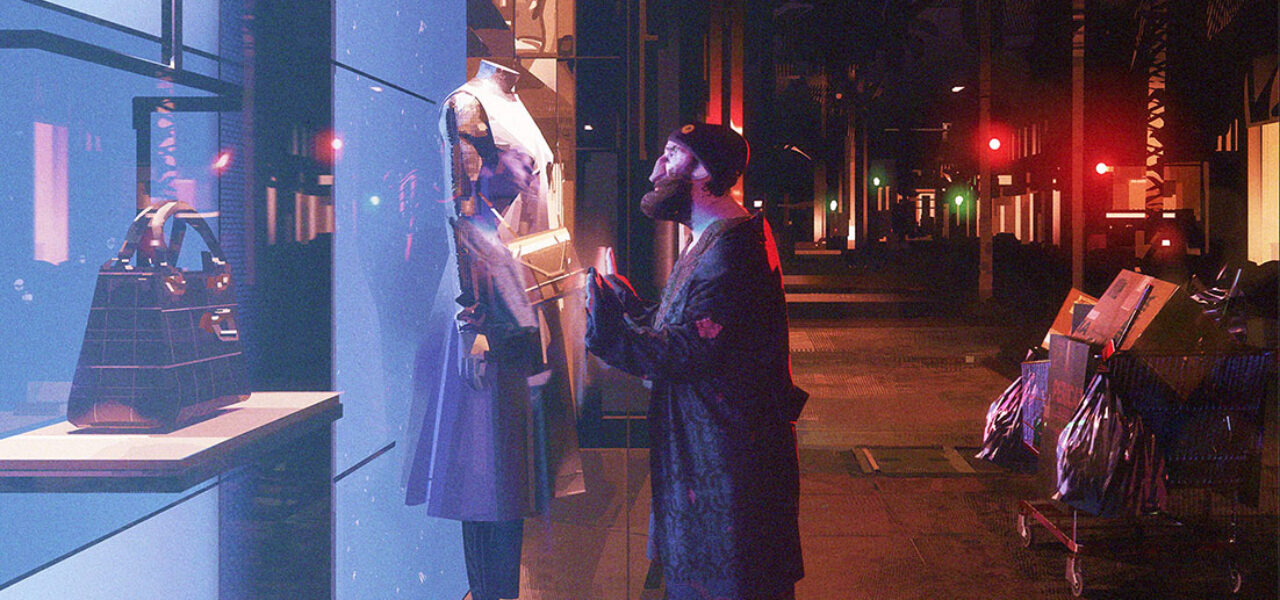

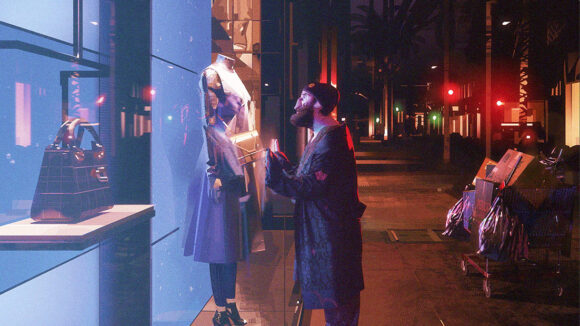

If that doesn’t convince you, well, maybe go to some animation festivals where one can regularly see experimental, poetic, and personal works that deal with an array of non-kiddie subjects: domestic abuse (Steakhouse), mental illness (A Family That Steals Dogs), adultery/murder (Night Bus), rape (Granny’s Sex Life), colonization, abuse, assimilation (Meneath), transgender issues (All Those Sensations in My Belly).

That’s just a miniscule sampling from the last year. I haven’t even started travelling back through animation history to toss out endless examples of radical animation: McLaren, Lye, Fischinger, Vanderbeek, Griffin, Bakshi, Baumane, Norstein, Pärn, Koyalyov, Mulloy, Hykade, Cournoyer, Tilby/Forbis, Landreth, Hobbs… I mean, I could go on and on with examples.

And look, The Windshield Wiper is a commendable work worthy of attention, but the idea that it’s something bold and groundbreaking is more than a bit of a stretch. The Windshield Wiper isn’t some radical, pioneering work that is changing the animation landscape. Mielgo might want to spend a bit more time checking out animation and short film festivals, where you’d find so much fresh and intriguing work that you’d see that “adult” animation is the norm, not the exception.

In that context, I find Mielgo’s comment (however innocent) as problematic as the other issues of the evening. It denied animation history. It rejected what exists, has existed, and will continue to exist. The remark also inadvertently reaffirmed the exhausting and erroneous belief that animation is, at its core, nothing more than entertainment.

At what point do animators wake up and realize they’re in an abusive relationship? Year after year, animators crave love from the Academy only to be let down and treated as afterthoughts. If this year didn’t drive that sad truth home, well, there’s not much to be done, I’m afraid.

Clearly, though, Chris Rock wasn’t the only one who got slapped in the face.

.png)