Why Was Estonian Animation Legend Priit Pärn Booted From His Country’s Only Animation School?

Two weeks ago or so I received a rather frantic email from a young animator studying at the Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA) in Tallinn. In it, I was told that the Estonian animation legend, Priit Pärn, had been quietly booted during a May 2016 election—in which he was the only candidate—from his teaching position at EKA.

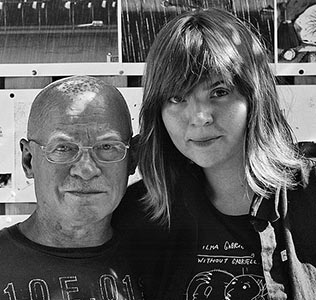

The students, many of whom have forked over a pile of money to travel to Tallinn (the Estonian capital) and study under Pärn (along with his wife Olga, who has been teaching there for about seven years), were angry and confused. Their subsequent appeals to the Academy’s administrators fell upon deaf ears so she was appealing to me (because I’d authored a book on Estonian animators and have some familiarity with the Estonian scene) to help their cause.

Now, before we dive into this Rashomon-inspired mini-drama, let me serve up a little plate of context.

Prior to 2006, when Pärn established the animation department at the EKA, there were no formal animation schools in Estonia. Until 1994, the only way to get an animation education was to find your way into one of the two major studios: Nukufilm or Joonisfilm. In between those years, the best solution was to take a four-to-six hour trip via bus and boat to Turku, Finland, where Pärn was heading up the animation department of the Turku Arts Academy. In fact, it was there that two future Estonian animators Ülo Pikkov and Kaspar Jancis studied. Given Estonia’s rich animation history and Finland’s lack thereof, it was a somewhat ridiculous situation: Estonians had to travel to another country to learn from one of the great Estonian animators (his films—including Hotel E, Breakfast on The Grass, 1895, and The Night of The Carrots—have won many international awards and influenced contemporary animation in both Estonia and abroad).

In 2006, Estonians realized the absurdity of the situation and fixed it. EKA applied for money to set up an animation department. Pärn created a teaching syllabus and brought on his former pupil, Ülo Pikkov, to be an assistant professor. Pärn’s wife, Olga, joined the department as a part-time teacher around 2008. (Pikkov has since left EKA leaving the Pärns as the primary instructors.)

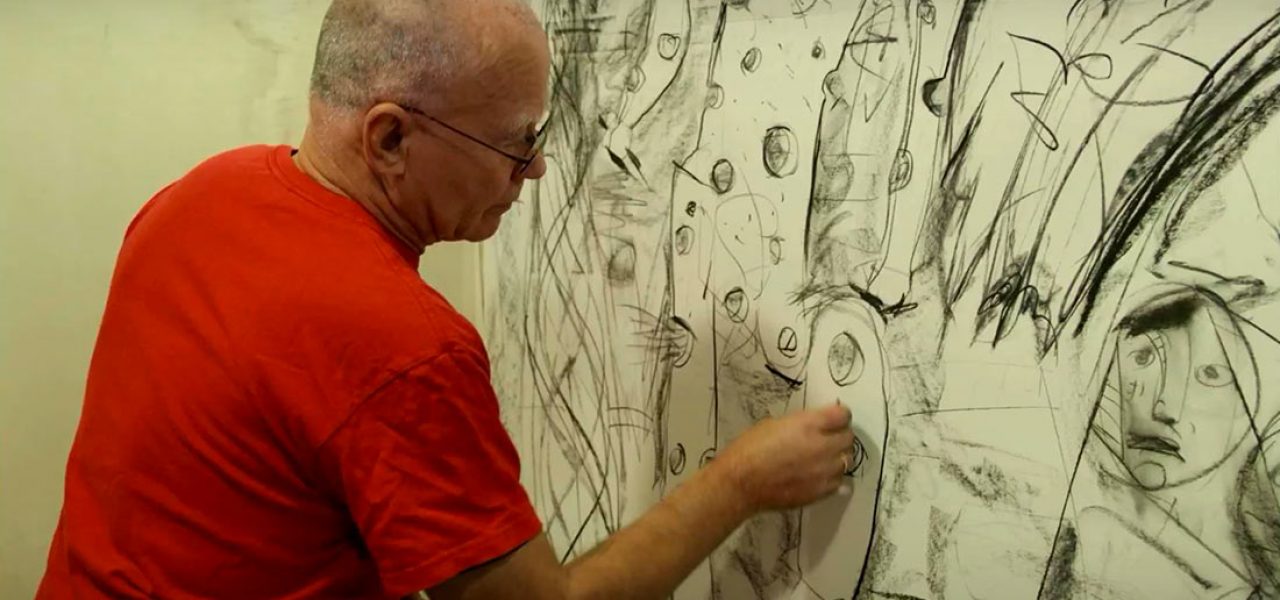

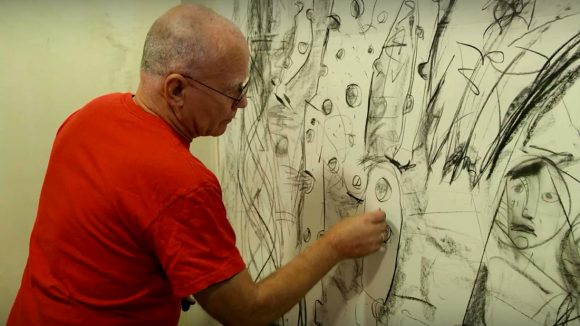

Under Pärn, the animation department thrived, attracting many native and foreign students while producing a number of festival acclaimed films and animators (e.g. Anu-Laura Tuttelberg, Helen Unt, Michael Frei).

The genesis of the current conflict goes back to 2014. Pärn was re-elected by the EKA’s council (this takes place every five years) to continue to teach and oversee the animation department. However, Pärn refused unless he was given a raise and Olga a full time job. A compromise was reached. Pärn would get a raise and Olga would be a part-time assistant professor, but Ülo Pikkov would take over as head of the department and, because the school was uncertain about their future budgets, the contract would only be for two years, not five. This was an ideal situation. Pärn would retire at the end of the five-year period and Pikkov would lead the school going forward.

Fast forward to May 2016. With Pärn’s contract schedule to end in September 2016, the Council of the Academy of the Arts holds an election to vote on the professor of animation. Pärn is the only candidate. Only 5 of 21 vote in support of him. Pärn’s day as head of the department is over (Pärn also refused a follow-up offer from EKA to become emeritus professor).

Now, this is about where I came into the story. Having known Pärn for 20 years, I know that he can be a stubborn and single-minded person. I cannot imagine him, for example, going to faculty meetings and being a rah-rah type (and we’ll come back to this later). Regardless, he’s always excelled at teaching and has helped nurture many outstanding animators. That so many students were outraged by the school’s decision and took immediate action to stop it is a testament to Priit and Olga’s impact as teachers.

So just how in hell does one of the most famous animators in the world get booted from his country’s only animation school?

Well, that’s where we get into the Rashomon effect (where multiple recollections of the same event contain conflicting information).

First, there’s the issue of the contract. In both an email to me and in an article from the Estonian daily, Postimees, it’s clear that while Pärn had a contract for only two years, he also believed that no election would take place for the standard five years.

However, a new European Law came into effect on January 1, 2015 that changed things so that all contracts could be without terms. This meant that the EKA was free—but not obliged—to have new elections whenever they desired. What upsets Pärn is that he feels the EKA were well aware of the impending new law but chose not to inform him.

Clearly, the EKA wanted Pärn out.

What they perhaps didn’t count on was the loud, angry voices of the students who were also heard by the international animation community. In the last couple of weeks, letters have been written, meetings held, appeals made, and movements started (yes, a “Je Suis Pärn” group has been started). Estonian media jumped on the story and Pärn took full advantage, blasting the school’s bigwigs left and right for what he called deceptive and unethical behavior.

EKA officials finally began to address Pärn’s public attacks in early June. Andreas Tali, the dean of fine arts at EKA, told the Ekspress newspaper that disloyalty was a major factor. In March 2016, upon learning about new elections, Pärn immediately wrote a letter to his students saying that the EKA doesn’t value his work and that he’s in negotiations with Tallinn University to move the animation department to their Baltic Film and Television School (BFM).

From EKA’s perspective, this was treason and cause for immediate dismissal.

However, while one former student and teacher, Helen Unt, admits that there was such a letter, she notes that the issue of moving to BFM “had been an open discussion for years already because most of our departments are in that school already, and when we moved there, the decision to move the whole department to BFM was also discussed on the highest levels.” Though discussions stopped at some point, Unt says that students and teachers continued to discuss the pros and cons of such a move. (As a side note, students also told me that the EKA has been without a single building for years, forcing several of their departments to take up separate buildings. This separation has no doubt played a factor in communication problems between departments and the school administration.)

One of the more telling explanations came from EKA Rector, Mart Kalm. In June 7th issue of the Postimees, Kalm points at perceived limitations of Pärn’s teaching as an issue. International experts are frequently brought in to evaluate school departments. In this case, two consultants (outside of animation) had heavy praise for Pärn, but encouraged the school to “change horses.” They believed that the animation department would be better served by opening itself up and diversifying. This would bring animation more in contact with the wider field of culture and contemporary art. In short, Pärn’s teaching is seen as narrow and old school (Pärn doesn’t deny that he’s using the same teaching system he developed in the 1990s).

It’s hard to pinpoint who might be right or wrong in this argument. Pärn’s teaching approach has been successful and students actually appreciate the ‘old school’/storytelling approach. Yet, one can understand the university’s thinking here, too. To prevent teachers/professors from becoming complacent (and boy, I’ve seen some deadbeat profs over the years) they have to show some development and refinements in their approach. Maybe Pärn could have taken the easy road and played their game (while staying true to his teaching philosophy), but that’s never really been his way, which is at least admirable.

Additionally, Kalm notes that some students and administrators desired bringing some fresh perspectives into the department. While other disciplines frequently brought in lecturers from abroad, the animation department has apparently been more closed and insular. Kalm also points to Pärn’s overall “lack of co-operation with people outside the animation world” as another obstacle.

Finally, Kalm touches upon what is clearly the heart of the matter: Olga Pärn. While there has always been some concern about a husband and wife running such a small department, it was accepted and likely offset by the presence of Pikkov. However, that all blew up when Pikkov left the animation department in January 2016 (Pikkov won’t comment on the situation other than to say that he has no plans on returning to EKA).

From what I can piece together, this is when things really start to unravel. While Pärn—who was named temporary department head after Pikkov left—believes he was hijacked with this sudden announcement of new elections, he couldn’t have been too surprised given dean Tali’s previous concerns about having Priit and Olga running the department (and it’s especially tricky if one is the boss of the other).

It likely didn’t help matters that during his election platform, Kalm states that, “Priit Pärn promised that when he retires, the department will be overtaken by his wife Olga.” This perceived dictatorial statement apparently angered members of the EKA council and was likely the final stamp in voting him out.

Kalm concludes by saying, quite rightly, that an artist is free with their creations or even when creating their own school, but when you’re working in a university, you have to be able to fit into the school’s culture and environment.

We can go back and forth on this issue for pages and pages. Each side, convinced that they’re right, will always have an earnest, thoughtful rebuttal. But, there remain many gaps in this story so while it’s oh-so easy to get swept up by sentiments like Je Suis Pärn, write fiery, impassioned protest letters from abroad, and turn this into a David vs. Goliath scenario, it’s important to remember that truth is a slippery, shadowy creature difficult to catch and even harder to hold down.

And what about the real victims here—the students—whose needs and desires are being overshadowed by this increasingly hostile and personal dispute.

What becomes of those current and returning students–many of whom came to EKA to learn from Pärn?

What about new foreign students who were recently accepted to EKA? (Some, apparently, have already decided not to come since hearing of Pärn’s departure.)

Both sides claim to care about the students.

Time, money, and ego will tell just how true that is.

Thank you to all those who agreed to be interviewed including Heinrich Sepp (who also translated all the Estonian newspaper stories) Lucija Mrzljak, Mart Kalm (EKA), Lucija Mrzljak, and Olga Pärn.

.png)