Director Mike Johnson On 20 Years Of ‘Corpse Bride’: ‘Proving Stop-Motion Could Be As Smooth And As Fluid As Computer Animation’

Twenty Halloweens ago, Tim Burton conjured Corpse Bride, a fantasy fable that spans the world of the living and the land of the dead. Building on the stylings of The Nightmare Before Christmas, which he had dreamt up with Henry Selick in 1993, Corpse Bride tells the tale of Victor, a skinny and melancholy young man who is to be married off to a shy and eligible young woman, Victoria. Fortunately, they find they get along well. Unfortunately, Victor has just accidentally married a corpse instead, thanks to an ill-advised placing of his wedding ring on the outstretched finger of a graveside branch mid song-and-dance.

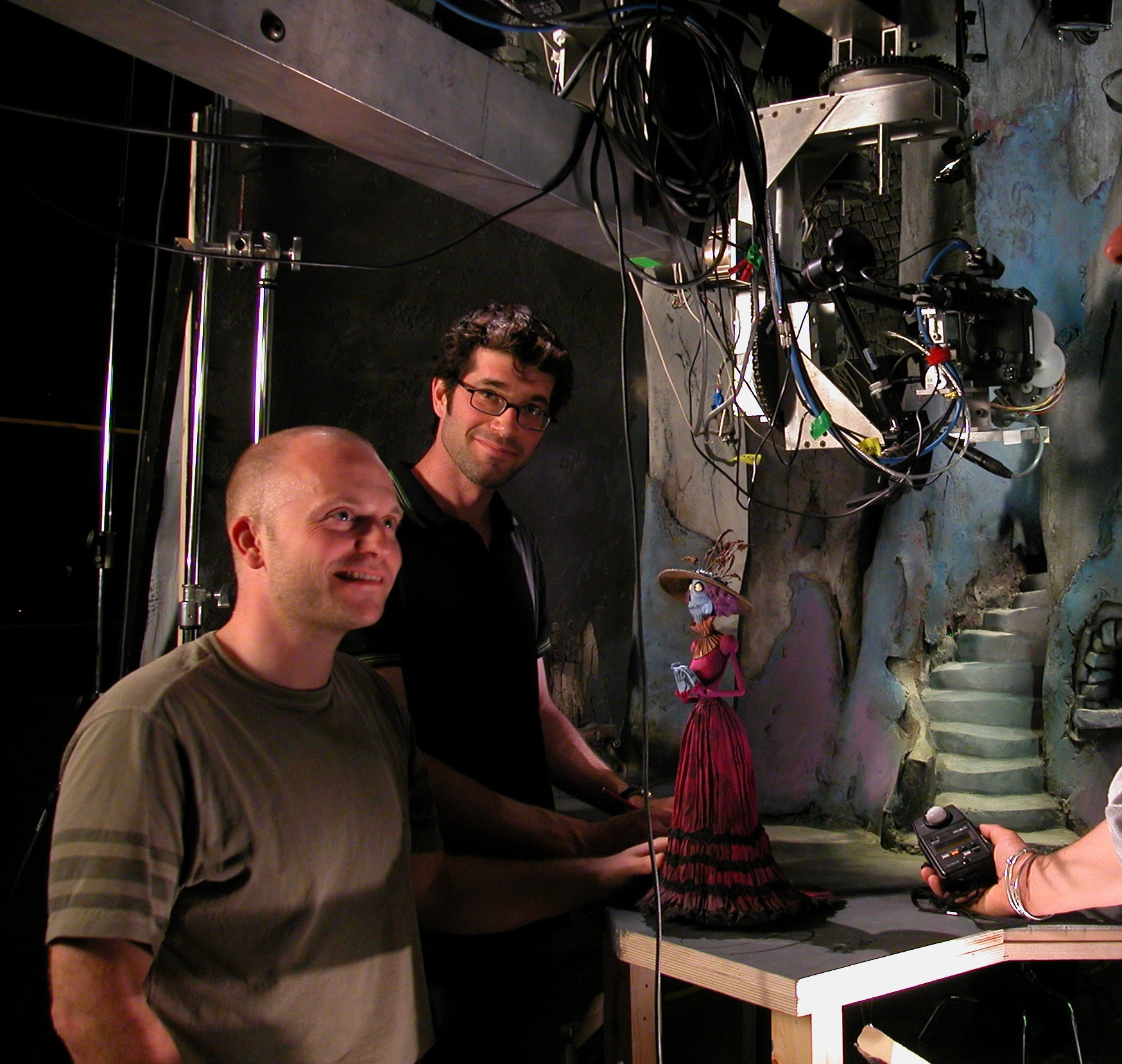

Tim Burton brought the initial ideas for Corpse Bride, but its animation was spearheaded by co-director Mike Johnson. In our exclusive interview, we spoke with Johnson about how Corpse Bride was brought to life, its legacy, and where animation took him next.

Cartoon Brew: How did this project originate, and how did you come to co-direct it? I’m aware that you worked on The Nightmare Before Christmas as a rigger and James and the Giant Peach as an animator – there seems to be a progression here.

Mike Johnson: Corpse Bride actually originated right after Nightmare Before Christmas. This project was first pitched to Tim Burton by storyboard artist Joe Ranft – he went to CalArts with Tim, and he was a key player in the early days of Pixar. He was the voice of the caterpillar in A Bug’s Life. He’s just an all-around creative guy. He brought that story, the original folktale, to Tim. But it didn’t get the green light for whatever reason. Other projects were going on, and it just sort of went away for about ten years.

When it resurfaced, I had done some short films, and I was directing a television series for Will Vinton Studios, which is now Laika. A producer there brought the project to Tim’s attention again, and they put me forward as a director. There were other candidates, but I think because of my short films and having that Tim Burton DNA of working in a small capacity on Nightmare and things like that, after meeting with him and talking about ideas for the film, he chose me for the job.

It’s interesting because in those intervening years, you took on projects such as the music video for Primus’ “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” which has a similar DNA to Corpse Bride, in that an underworld inhabitant invades the land of the living. Was the Corpse Bride idea circling in your mind when you took on projects like that one?

Obviously, there’s a big Tim Burton influence and inspiration in my short films, but I hadn’t really been thinking about Corpse Bride. Everyone who was in the stop-mo scene, as far as my group of people I worked with at that time, had sort of forgotten about that idea. They thought it had just gone away. When I made “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” it wasn’t with the intention of getting involved in Corpse Bride – but I do think maybe when Tim saw that film, that also helped me. I think he understood that I understood the aesthetic that he was after.

There was a lot of story work that I was responsible for. My job was basically to manifest this vision under Tim’s supervision. I would meet with him and he would give me sketches, notes, and directions to feed back to the crew and implement. He was very busy during the production of Corpse Bride, making Big Fish and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. It’s obviously his world, his style, his concept, but it was my job to carry that forward and manifest it.

The animation in this film is very fluid and smooth. I expect fewer people are aware that it’s stop-motion than they are with Nightmare Before Christmas and James and the Giant Peach. Were you trying to hide the film’s stop-motion nature, or was it more to chart new heights of what you could achieve in stop-motion?

It was more to chart new heights. At that time, the Pixar films were the dominant art form as far as feature animation. It was less about creating a funky stop-mo aesthetic – it hadn’t really turned that way yet – it was more about proving that stop-motion could be as smooth and as fluid as computer animation and still be emotive, still have texture. You know, at that point, I considered chattery stop-motion, pops, and things like that as flaws. Of course, since Corpse Bride, it’s come around the other way – Wes Anderson and all these films that embrace the texture of stop-motion to set themselves apart. I can see the value of that now that, like you said, audiences might not know the difference between stop-motion and CG. I think the Laika films now do take it too far, where it really doesn’t matter – if they had made those films in CG instead of stop-motion, no one would know the difference, because it’s such a hybrid. Back then, it was a different world. It was about advancing the techniques but still embracing them. That was the idea behind the fluidity of the animation.

CG is used a little in this film, isn’t it?

There’s a little bit of CG in there. A tiny amount. Twenty years ago, it wasn’t as accessible, and the tools weren’t advanced. So we had a little bit of green-screen backgrounds, things like that. There was no CG character animation, but the Bride’s veil was CG. Only in a few shots – so we could create that flowing, transparent, sort of underwater effect through stop-motion. But it took the animators days to pull that off. The solution to that, because we were under scheduling pressure, was to have three shots that had a CG veil. And then we also had her take her veil off at a certain point, when she throws it on the ground – that released us from having to animate her veil in a handful of shots. Even just that handful of shots made a huge difference in the schedule. So there is that little bit of CG in there, but as far as real character animation, it’s all pure stop-motion.

In regard to that feel, the stop-motion nature of the characters is more apparent for the viewer once we reach the afterlife – there’s a tactility to the character models there. The tactility and thumbprints of stop-motion characters always make me think of them as being very alive somehow. And so, the land of the dead ends up feeling more alive than the land of the living. Was that an intentional duality?

That was intentional in the design of the characters, the lighting, the stages, all of that. I hadn’t really thought about how that carries through in the animation until you mentioned it, but I guess that’s true. Some of that might be due to the fact that we didn’t start shooting the land of the dead sequences until later in production. So maybe we were able to let it be a little more fast and loose due to scheduling. I guess it does give it a tactile quality that helps reinforce the difference in tone that we’re trying to achieve between both worlds.

What was it like directing and animating in a greyscale palette for the land of the living sequences? That must have been an interesting challenge.

It was interesting, and I really liked it. I feel the land of the living – for all its monochromatic palette – was more successful to me than what we ended up with for the land of the dead. I wish that we’d had a little more time to play around with the atmospheric elements there. Some of the concept art was just a bit more ambitious. But I was really happy with the land of the living stuff – and we did it the hard way. We didn’t just dial out the color; everything was painted in a limited palette. We were trying to make it look like old tintypes and daguerreotypes. Even with the rigid formality of the staging of the shots, I was very pleased with the way that came through. I like the subtlety of that palette, seeing the little bits of purple and things that still come through and give it some life.

Are the dour, less expressive faces of the characters in the world of the living easier to animate than the more expressive ones in the land of the dead?

Yes and no. For the land of the dead characters, we could have a less complex mechanism for those puppets. If it’s a skull with a hinged jaw, that’s easier for an animator to work with than the mechanisms behind the silicone masks of the living characters – those were much more challenging for the animators to work with. Victor’s parents had a very limited range, but Victor himself had to have a wide range of expression, and obviously, the Corpse Bride had a very complicated facial mechanism as well.

Similarly, I’m curious as to whether the skinny, long-limbed characters are easier for you to articulate – and whether that might be part of the reason for Nightmare and Corpse Bride’s aesthetic direction.

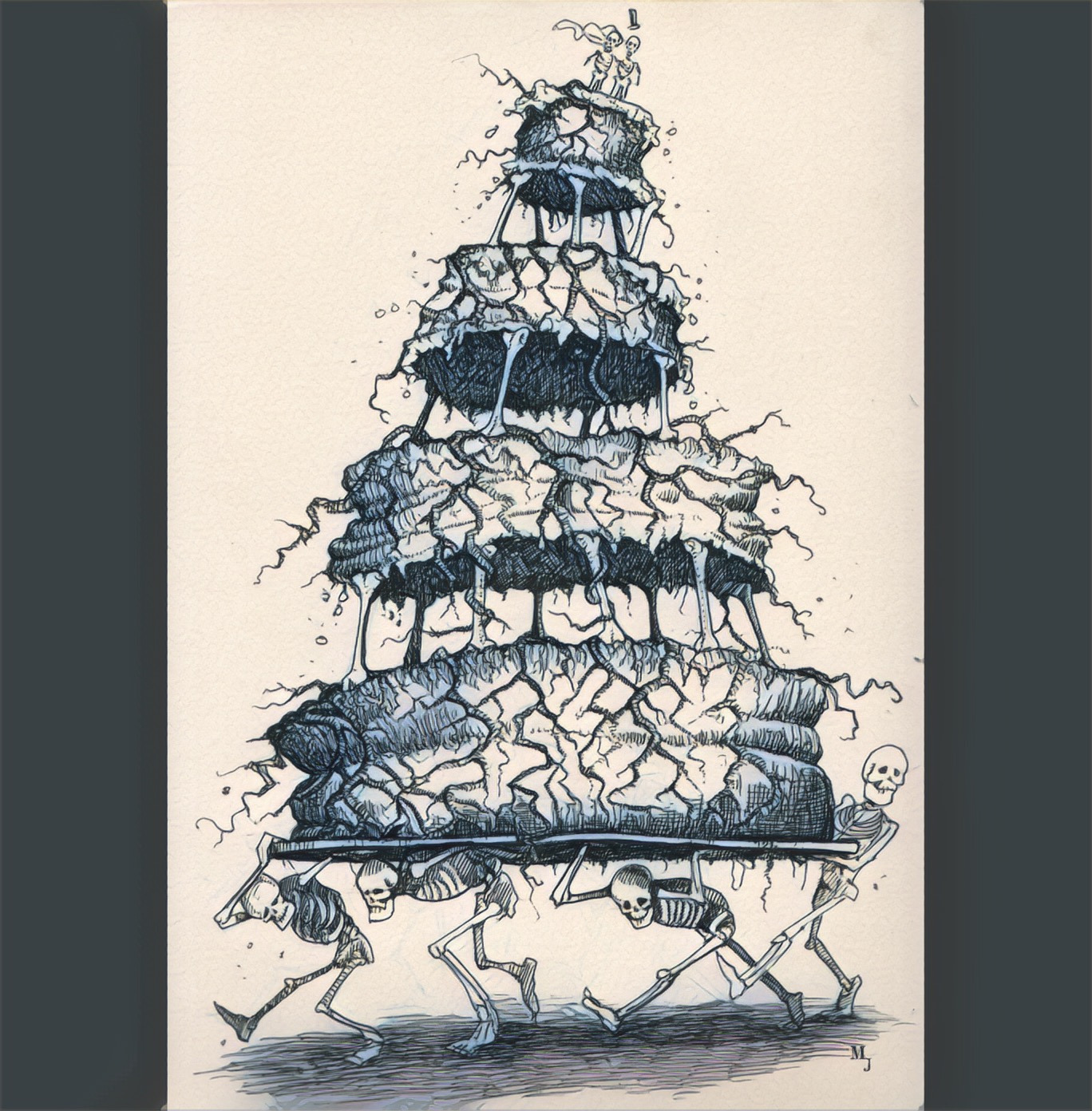

When Corpse Bride was first pitched as an idea, it was Joe Ranft’s write-up of that folktale, but also a handful of drawings that he and Tim Burton had done. The tradition of Jack Skellington and Sally was very much baked into the initial designs of Corpse Bride.

Those skinny, long-limbed characters – I guess maybe it’s easier to get clear, expressive poses with designs like that, but animating them – especially back then – rigging was more complicated. We couldn’t digitally erase rigs as easily, so the rigs had to be hidden in the shot. That made it much more challenging to animate.

A character like Victor with a big head and a tiny little ankle joint standing on one foot is kind of a marvel of physics. I think the engineers who built those armatures and those puppets, Mackinnon and Saunders, deserve a huge amount of credit for being able to bring those designs to life in a three-dimensional world.

There are some abstract sequences in the film. The “Remains of the Day” musical number at the center has a lot of leaping limbs and acrobatic figures. Was that all stop-motion?

It’s all stop-motion. When the shadows are cast upon the wall, that little moment where the story is told through shadows, that was obviously two-dimensional animation. But all the dancing and leaping around was stop-motion and puppets – and sometimes specialty puppets that could be more flexible. We had some skeletons that were just wire instead of the ball-and-socket armatures, which would give them a little more flexibility. There are ways to achieve that look.

It’s a particularly cool sequence because skeletons are such a pivotal part of the lineage of achieving clever and special things in animation, from Silly Symphonies onwards.

Yeah, for sure. That was a big influence, the skeleton dance from the early days of Disney, all the way through to Ray Harryhausen in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and Jason and the Argonauts. Like you said, there’s a huge tradition of skeletons and stop-motion, and we wanted to acknowledge that where we could.

The climax of the film in the church is action-heavy. How did you pull it off?

We wanted a big action sequence at the end – something exciting – because so many of the sequences in the film are low-key, slow-cooking sequences. It was a lot of fun. There’s a moment where Victor swings the sword and it hits the stone pillar behind Barkis – sparks fly. Even that was done with old-fashioned practical effects, where the animator would burn a little bit of steel wool. He would have to light it on the set, and as it fizzled and sparked, he would shoot the frame of animation.

Could you tell me about your other feature, Ping Pong Rabbit? There’s very little information about it online. Did it get released?

It didn’t get released. An American producer approached me with a deal in China to make it. I worked on it for several years. But this was right before China broke big with some of their animated films – great films. This was a couple of years before Ne Zha came out, and a lot of people were still unsure about where Chinese animation would go. After a few years of production, they shut the doors on that one. There were a lot of factors involved. But sadly, it never made it to the screen. We had it three-quarters of the way done.

It’s a different experience working in CG. It’s still visual storytelling, and the same rules apply as far as that goes. But technically, day to day, it’s just not the same as stop-motion. It doesn’t have the same kind of excitement. Just the fun of being on set, with real miniature sets and puppets. Since I came up from and really climbed the ladder in stop-motion, from puppet making up to directing and animation, I understood every aspect. That helped me as far as directing stop-motion. I could understand how to save some time for a setup. Or I would understand that the animator would need an extra day on a shot. With CG, I didn’t have that background. Someone would come up to me and say, “This shot won’t be ready for two weeks.” And I’d say, “Why not?” I would get some kind of technical, computer answer, and I had to take their word for it. So it was difficult transitioning from stop-motion to computer animation, and not as enjoyable for me.

You’re credited as a guest animator on Anomalisa. Could you tell me what your work on that entailed?

That was just a little bit – I was in there for about two weeks. Actually, that was right before the Ping Pong Rabbit job took off. At that point, the stop-motion community was still pretty small and intimate. I got a call one day from a friend working on it who said, “Hey, they need help. Can you come in and help them out for a couple of weeks, knock out a couple shots?” And so I did. The shots were not glorious. In the auditorium at the end, when he’s starting to have a nervous breakdown – I did a couple of wide shots there, a close-up when she’s singing that Cyndi Lauper song in the hotel room, and a reaction shot of him. So I just did three shots on that film over the course of two weeks, and then I had to move on to Ping Pong Rabbit. But it was nice of them to give me that credit, and it was nice to kind of reconnect with a lot of animators I’d known since Nightmare who were working on it. As far as the really epic, crazy, minute-and-a-half-long animated shots that are in that movie, I wasn’t involved in them. But I saw them going down, and I was amazed by what they were reaching for with that film.

What, if anything, are you working on in the world of animation these days?

After Ping Pong Rabbit folded up, I continued to work in China developing projects until Covid hit. Due to Covid and all the disruption it brought to everyone’s lives, my wife and I decided to move from LA to Texas to be closer to my parents. We bought a twelve-acre farm, and I got into beekeeping. I now maintain 25 hives and work full-time as a beekeeper. Surprisingly, many stop-mo skills carry over into beekeeping. I’m happy to say I’ve won multiple Blue Ribbons for honey this year at Honey Shows and the Texas State Fair. I wasn’t expecting to change careers, but I guess I’ve retired from animation – for now.

All behind-the-scenes and concept images courtesy of Mike Johnson’s personal archives.

.png)