Worshiping At The Altar Of Cel Animation: The Five-Year Journey Of Spktra’s ‘Spirit Jumper’ Music Video (EXCLUSIVE)

By the time “Spirit Jumper” finally emerged after nearly five years of production, it had already lived several lives. Finished as a song on January 1, 2020, it sat in limbo while its creator, electronic musician and producer spktra (Josh Fagin), embarked on a far less predictable second act, teaching himself how to board, direct, produce, and finish a hand-crafted animated short that treats a music video less like marketing collateral and more like a dialogue-free narrative film.

“I always had it in my head that I didn’t want it to feel like animated stuff happening while music plays behind it,” spktra tells us. “If you turned the music off, it should still tell a story.”

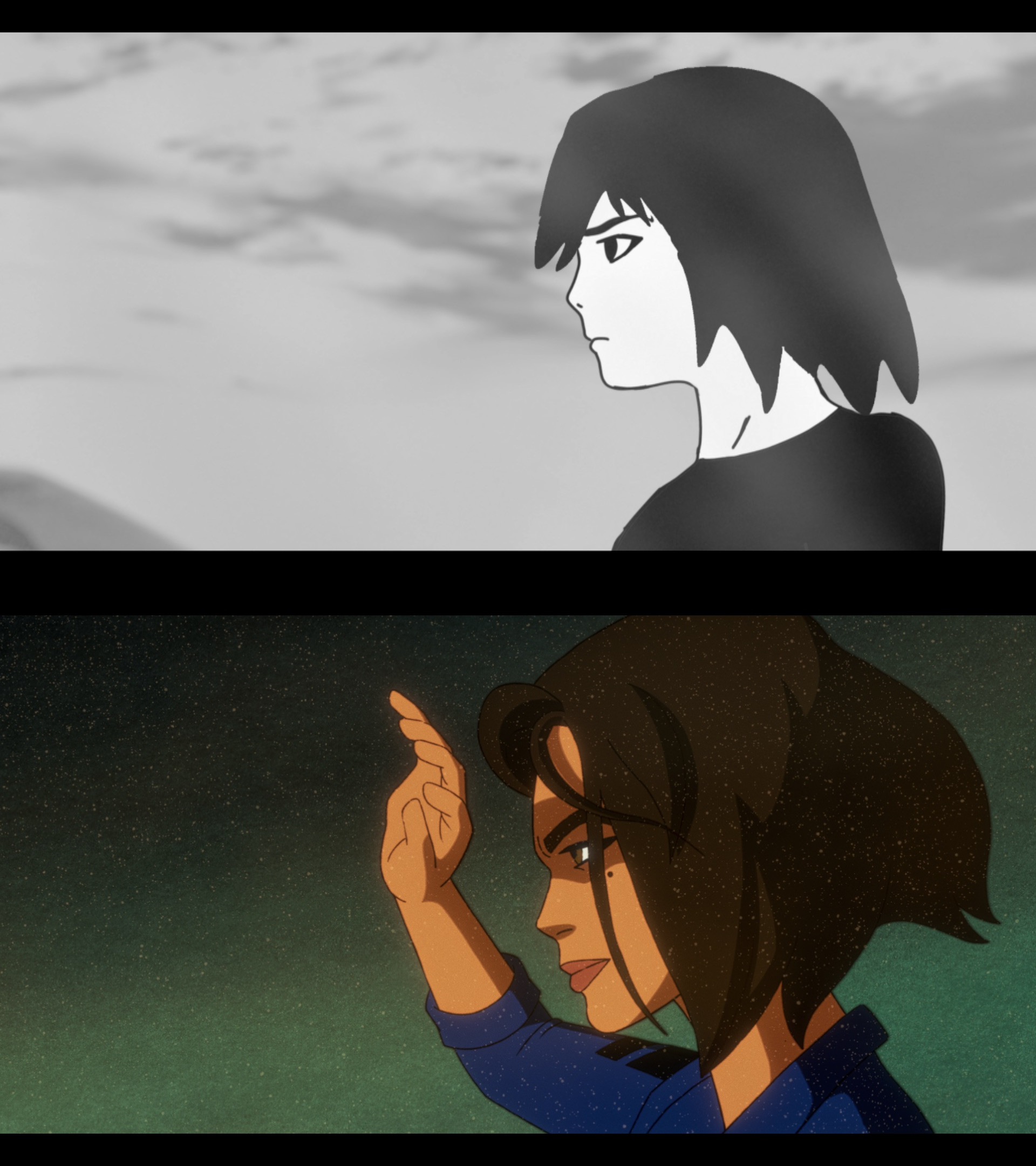

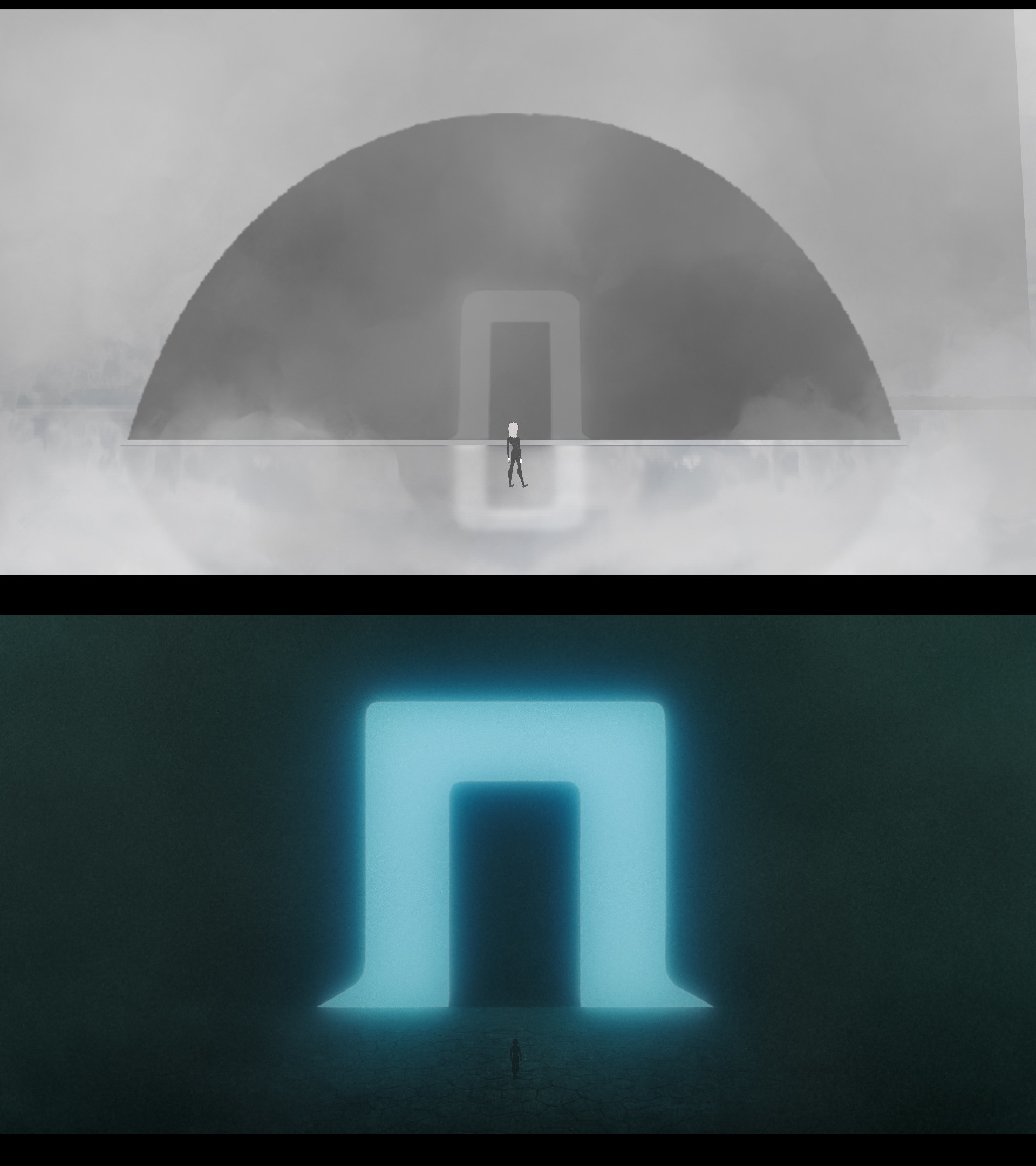

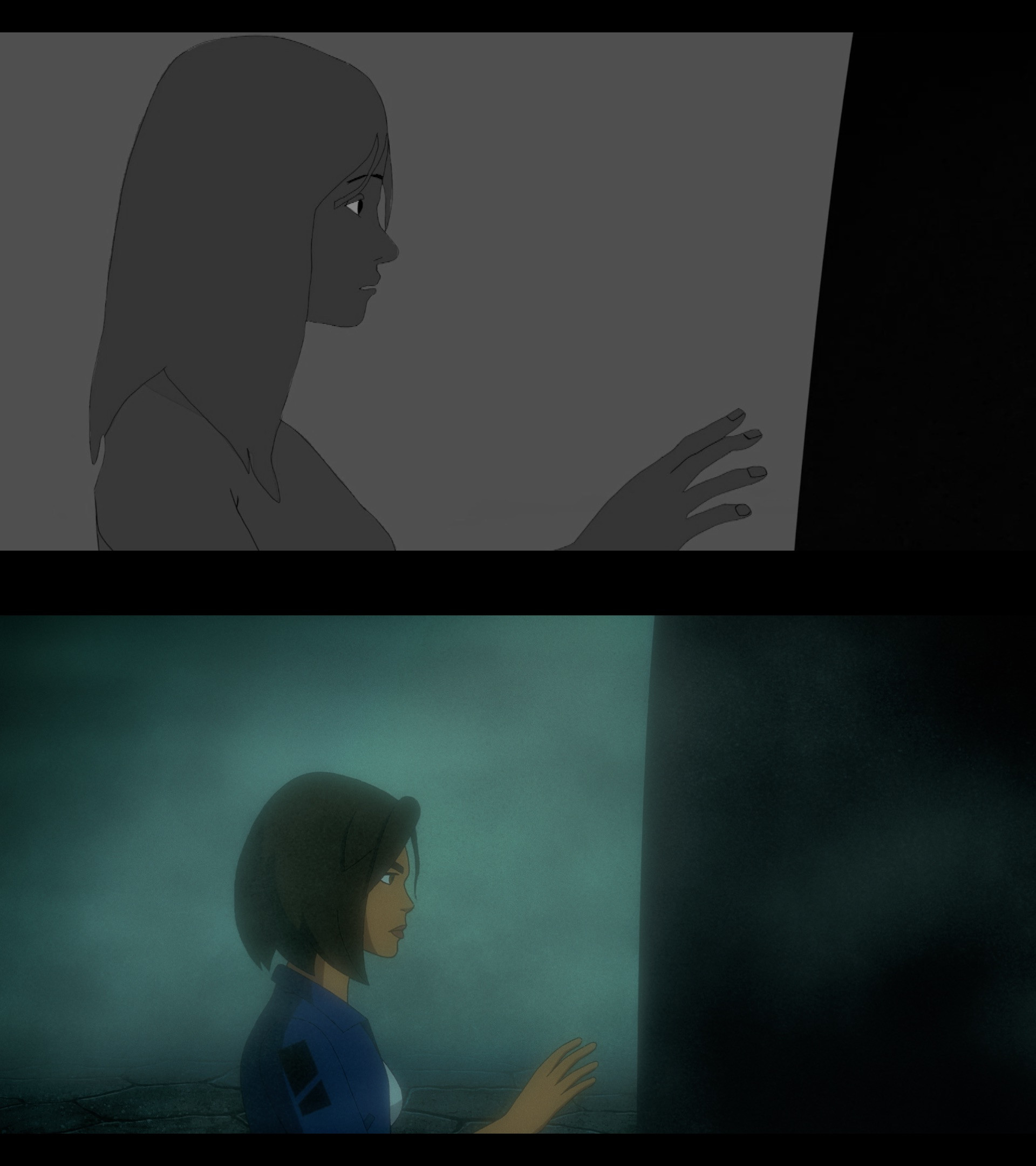

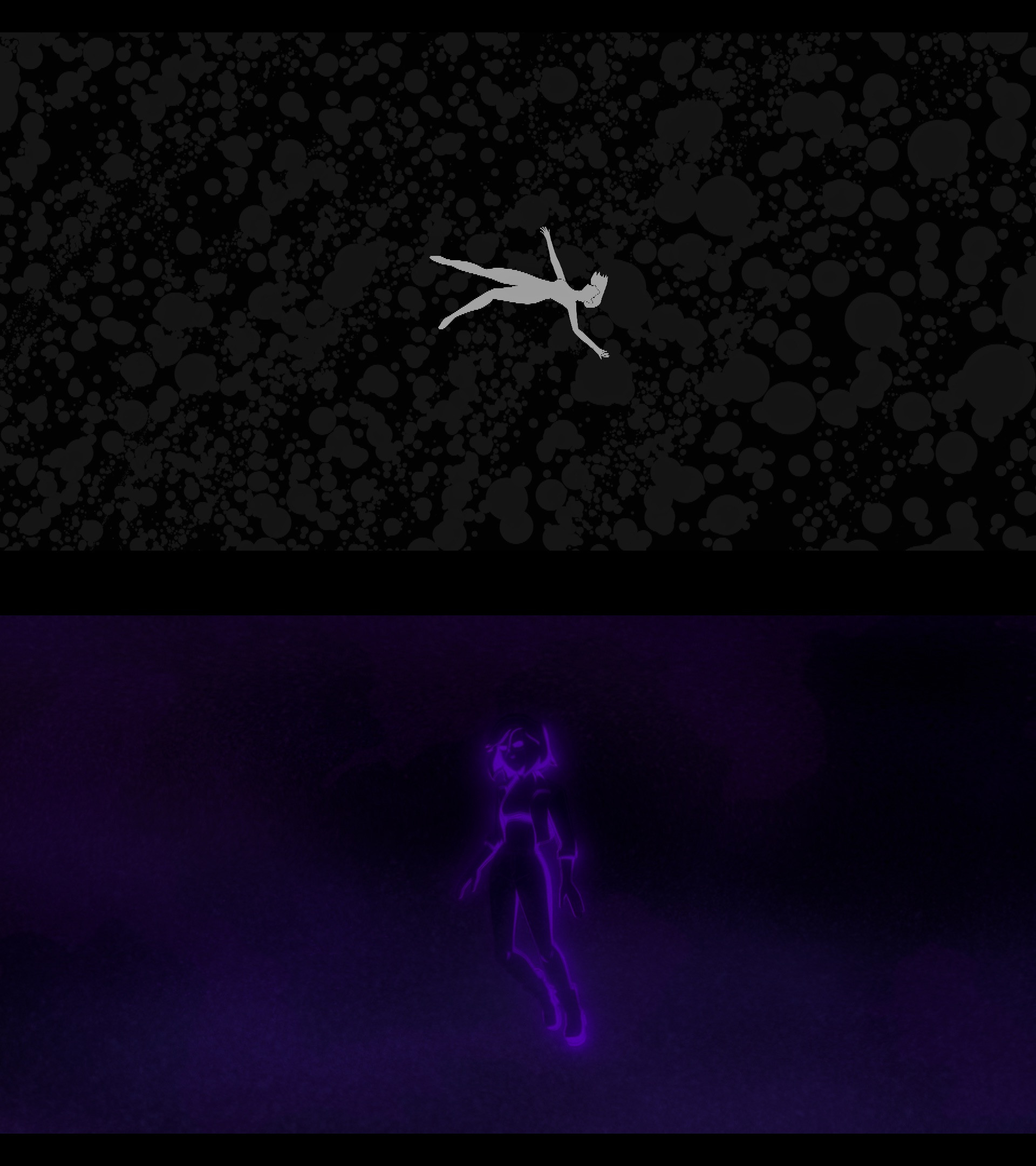

That mandate sets the tone for Spirit Jumper, a three-minute-and-forty-second short that feels like a restored artifact from the late ‘90s. Not a pastiche, not a cheap VHS or tube TV filter, but something closer to what you’d see if a lost ‘90s reel were carefully scanned and cleaned for a 4K Blu-ray restoration.

“It’s not about nostalgia for CRTs,” spktra explains. “The idea was: this was sitting on a reel somewhere, and we restored the negative. This is what’s underneath all that broadcast gunk.”

An Unlikely Story Artist

Spktra is upfront about the fact that he did not come from animation. “I’m a musician and producer first and foremost,” he says. “I’m not even in the animation industry.”

That lack of institutional baggage may be part of why Spirit Jumper feels so unconcerned with contemporary pipeline orthodoxy. Instead of handing the project to a studio, spktra decided, incorrectly by his own admission, that he could simply do it himself.

“How hard could it be?” he laughs. “Well, it was very hard, I tell you, five years later.”

When the plan struck him, he first wrote the story, cut the animatic himself, and edited the entire short before animation began. “I needed to show whoever I ended up working with that this was a full piece,” he says. “Nobody’s going to jump on a project from someone who can’t draw, only has the idea of a plan, and has never done this before.”

That animatic became the project’s foundation, allowing collaborators to engage with a coherent structure rather than a loose concept. The approach paid off, but not immediately. The short was effectively animated twice, an early attempt scrapped when spktra realized he was still “changing things” instead of directing decisively.

Cold Emails, Dirty Lines

With no studio backing and no animation address book, spktra built his team by reaching out to artists whose work he admired.

“I started collecting artists who I thought fit the style,” he says. “People who were willing to do the opposite of industry standard — less clean, more texture. Someone who’d say, ‘No, this is too clean. Make it dirtier.’”

The most pivotal early collaboration was character designer Glenn Wong, best known for his work on Batman Beyond. “That connection was huge,” spktra says. “We spent probably nine months just dialing in the characters before anything else.”

Viewers familiar with DC’s late-’90s animated favorite will recognize the DNA immediately, especially in the human protagonist. That lineage isn’t accidental. “When people pick up on that reference, I’m thrilled,” spktra says. “The texture, that’s the thing.”

Two Animators, Hundreds of Shots

Ultimately, almost the entire video was animated by just two people: animator Tamás Pazmany and his partner Regina Nemes.

“That’s the part that still blows my mind,” spktra says. “Two people. That’s it.”

Working primarily in Toon Boom Harmony, Tamás deliberately introduced line breaks and inconsistencies into his cleanup. “Those breaks mimic what happens when animator lines get transferred onto cels,” spktra explains, adding, “It’s not about sloppiness. It’s about character.”

Tamás also brought an unusual rhythmic sensibility to the work. “He has this incredible ability to animate on threes that feel like ones or twos,” spktra says. “The timing just feels right.”

That musicality wasn’t coincidental. spktra is a jazz drummer by training, and Tamás is a jazz bassist. “We didn’t have to explain things,” spktra says. “We were speaking the same language, tempo, rhythm, when to bend time instead of locking to it.”

Studying Cels

If the animation behind “Spirit Jumper” was disciplined, the finishing process bordered on obsessive.

After receiving cleaned linework, spktra moved into Clip Studio Paint, where he colored and processed every single frame himself. “I treated every frame as if it was being xerographed onto a cel,” he says.

To do that, he built massive, custom auto-actions, scripted macro chains that degraded lines, shifted density, and subtly destabilized color. That required a significant amount of research. “There’s almost no research on how film affects animation,” he notes. “There’s tons on live-action film, but very little on animation shot to film.”

As with animation, color, too, followed cel logic rather than modern conventions. “With cels, every color is intentional,” he explains. “You’re not just multiplying shadows with black. You’re shifting hue. We found a way to do that digitally without throwing away what the computer can do.”

Evangelion, Treasure Planet, and the Long Shadow of 2003

Influence-wise, “Spirit Jumper” wears its lineage openly. The film’s existential sci-fi tone echoes Neon Genesis Evangelion, while its broader philosophy reflects a belief that 2D animation was prematurely abandoned at the studio level.

“In 2003, Treasure Planet changed the course of animation history,” spktra argues. “For better or worse.”

What followed, he suggests, wasn’t evolution but abandonment, an industry-wide pivot toward realism that misunderstood what made drawn animation powerful in the first place.

“You can’t call 2D animation unrealistic,” he says. “That’s like calling a painting unrealistic. It’s inherent to the medium.”

Texture, he believes, is the missing link. “Animation is moving paint. We don’t really do that anymore. And I think people respond to it, even if they don’t consciously know why.”

What’s Next

Spirit Jumper was financed entirely by spktra, funded through a separate software business he built alongside his music work. “I own 100% of it,” he says. “That’s rare, and I know I’m lucky.”

So now, he’s releasing the result of five years of relentless education and hard work, in a moment that becomes more bittersweet as it draws closer. “There’s a sadness to releasing it,” he admits. “Because it means I’m done working on it.”

That said, it also marks a beginning. “Now I know what I’d do differently. What I wouldn’t have to relearn. My hope is that this isn’t the last thing, it’s just the first.”

For an artist who resurrected the ghost of cel animation frame by frame, that feels inevitable.

CREDITS:

Written, Directed, and Edited – spktra

Storyboard – spktra

Producer – Michael Fish

Producer – Jessica Wen

Color – spktra

Compositing – spktra

Animation Supervisor – Tamás Pazmany

Animation – Regina Nemes

Background Art – Alfie Marley

Character Design – Glenn Wong, Louis Picard, Zac Plucinski

Color Stylist – Chris Hooten

Special Thanks – Eric Williger

.png)