‘Ping Pong’ Recap: ‘The Wind Makes It Too Hard to Hear’

“No man so good, but another may be as good as he.” -Thomas Fuller

Anime wunderkind Masaaki Yuasa returns to the small screen for a fourth time in this adaptation of indie manga artist Taiyo Matsumoto’s underground comic hit Ping Pong (1996-1997).

Studio 4°C’s feature Mind Game (2004) introduced the world to a new anime director with a vision unlike any other: gleefully hand-drawn, exploding with colors, viscerally thrilling. His characters twisted like rubber, ballooned in odd perspectives, and exploded off the screen in an animated frenzy. But behind the visual orgy was a gritty, deep-felt story about violence, pathos, humiliation, lust, and redemption. Nowhere in sight were giant robots, magical girls, or tentacles. Even compared with illustrious predecessors like Yoshinori Kanada, Masaaki Yuasa’s unique and original talent stood its ground.

Masaaki Yuasa’s example belies the notion of anime as a monolithic blob of sparkly-eyed cliches. As it turns out, Masaaki Yuasa is but one in a coterie of talented anime creators laboring in the shadow of the colossus of the anime industry and its lock-step of design ethos and tropes. You have to dig, but there are pearls in the slop. Anime is in fact best when it doesn’t look the part.

The reward of following Masaaki Yuasa’s output since then has been to watch a director as unpredictable as he is imaginative. Despite having a unique drawing style he could exploit, he is unwilling to rest on his laurels. He re-invents himself in each new production. The expressionistic, brutal realism of his Romeo & Juliet body horror comedy Kemonozume (2006) gave way to the sleek abstraction of his retro-stylized science fiction epic Kaiba (2008) and then the Borgesian theatricality of his cerebral high school drama Tatami Galaxy (2010).

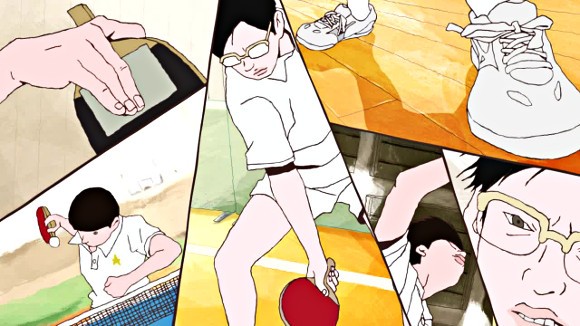

Ping Pong returns to something close to the sketchbook realism of Kemonozume, but through the lens of the peculiar and unmistakable style of Taiyo Matsumoto. Just as Katsuhiro Otomo did years before, Taiyo Matsumoto invented his own novel form of realistic caricature that was distinct from any other manga artist, but laden with creative bizarro ideas in the spirit of Moebius and drawn with a wobbly, meandering line reminiscent of Egon Schiele. His Ping Pong elevated a whimsical sport few take seriously to the level of dynamic, furious Olympian death matches.

Masaaki Yuasa translates all of this into animation. The character drawings have the same dynamism and wobbliness that makes Taiyo Matsumoto’s manga so delicious to behold. There is some variation in style in the first episode, but overall the episode renders beautiful homage to Taiyo Matsumoto’s style.

That’s something not easy in commercial animation. Even if your key animator gets the line right, it requires special effort to make sure the inbetweening stage doesn’t kill the line, which is essential to getting across Taiyo Matsumoto’s unique feeling. Even if they’d gotten the designs right but killed the line, something would have been missing. It’s not surprising coming from Yuasa & co., who did Robin Nishi’s indie comic Mind Game justice, but it’s a relief. It’s rare that animation captures the idiosyncrasies of a comic artist’s genius due to the inevitable flattening-out effect of the various steps in animation. Shigeru Mizuki’s Gegege no Kitaro has been adapted numerous times, none in a way that remotely resembles the art in the original manga.

Ping Pong is being produced at one of Japan’s biggest and most venerable studios – Tatsunoko – and perhaps it’s in managing to achieve this on a short schedule that the big-studio expertise of Tatsunoko comes in. This is Masaaki Yuasa’s first involvement with the studio, so it will be interesting to see what new faces are brought in. His first three series were all produced at Madhouse, which has seen a brain drain since the studio’s sale to Nippon Television in 2011.

Masaaki Yuasa’s right-hand man as character designer and chief animation director remains, as in all previous efforts, Nobutake Ito, the animator who brought to life the climax of Mind Game:

Nobutake Ito is not only versatile enough to be the designer of characters as distinct as those in Kemonozume and Kaiba, but also has the stamina and speed to bring them alive in dynamic and nuanced animation in the short schedules of TV production. He is always in the fray on the animation floor, unlike many designers who take no part in bringing their designs to life.The animator team fairly clearly falls into two categories: Yuasa associates and Tatsunoko animators. I’ll be providing a list of the key animators for each episode at the end of each post. Yasunori Miyazawa has been a regular presence in Masaaki Yuasa’s productions (Kemonozume 8, 13; Kaiba design assistance; Tatami Galaxy 1, 5, 7). He has a loose drawing style, disjointed sense of timing, and creative but decidedly odd visual tendency that makes his work easy to distinguish and a good match with Masaaki Yuasa’s work. (clip)

Maru Kanako is a talented animator active since 1996 who has also been a regular in Masaaki Yuasa shows (Kemonozume 11, 13; Tatami Galaxy 9, 11). She notably singlehandedly animated episode 18 of Casshern Sins. Izumi Murakami is a new animator who drew her first key animation in Madhouse’s Death Billiards short last year. She presumably hails from Yuasa’s Madhouse connection.

The other four key animators listed for this episode presumably hail from the show’s Tatsunoko side. Tatsuro Kawano created the short Loud House in 2011 while a student at Kyoto Seika University before entering the industry at Gainax and then moving to Tatsunoko:

Kei Masaki was the lone animator of Sonny Boy & Dewdrop Girl, the latest short by Hiroyasu Ishida:

Tomomi Kawazuma is also a new face and has previously worked on Tatsunoko’s Gatchaman Crowds.

Masaaki Yuasa storyboarded the first episode, and though he’s credited with script it must be assumed he boarded directly from the manga. He brings the 2D world of the manga to life through tricky three-dimensional simulated camera movements like the one following the ball during the duel between Peco and Kong. The camera tracks the ball as Peco serves, and seems halt in mid air, change direction, and zoom back towards Peco after Kong’s racket hits home. It makes for magically disorienting and exhilarating viewing. The cross-hatched screens are a tactic that hark back to the manga. The beauty is that Yuasa disappears into Taiyo Matsumoto. Rather than grandstanding with out-of-place flourishes, he is subservient to the material.

Masaaki Yuasa’s storyboards have been released in book form on previous occasions and are a marvel to behold. Although extremely roughly drawn, they’re detailed in the directions and full of vitality that makes them works of art in their own right.

The characters’ various movements during the ping pong training sessions in episode 1 are depicted meticulously in a convincing way despite the roughness of the drawings. Ping pong is a fast sport and the action happens in a split second. Moves are subtle and games are decided in the blink of an eye. The anime does an impressive job of capturing the nuances of this and the momentum of the players’ bodies.

Anime is known for chasing short-cuts, but fans of animation in anime have long known to look to sports anime for some nice animation, as the material inherently demands more movement and tends to bring out the fire in animators. Keiichiro Kimura’s animation in Tiger Mask (1969) is a classic such example and was notably the inspiration for Masaaki Yuasa’s previous effort, the Kickstarter short Kick Heart:

Ping Pong’s great ancestor in the sports anime genre is Star of the Giants, the seminal 1968 TV show produced by Tokyo Movie that established the spokon genre as we know it, with its tropes of macho angst, noble rivalry, and dramatically exaggerated calisthenics. True to the genre, we’re regaled with obscure terms like “right penhold grip” and “pips-out hitter” that educate us about the minutiae of the sport. But at the heart of every sports anime, as with sports, is human striving and rivalry. So it is with Ping Pong: Episode 1 introduces us to the outward rival, Chinese visitor Kong, and the buddies Peco and Smile who may eventually bud into spiritual rivals.

As with Tekkonkinkreet’s White and Black, the show’s star is an elegant yin-yang dual protagonist: Smile, the emotionally underdeveloped and unsmiling straight man to buddy Peco’s hubristic self-confidence and initiative. The beauty will be in seeing how their personalities intertwine and develop as high school ping pong provides the substrate of their emotional growth into mature adults. The quote at top from Thomas Fuller sums up the human conflict at the heart of Ping Pong as well as every antecedent in the genre of sports anime.

Note: This recap is based on the original Japanese language version of the episode.

Ping Pong Episode 1: The Wind Makes it Too Hard to Hear

| Storyboard: Script: Series Structure: |

Masaaki Yuasa | |

| Episode Director: | Takehiro Kubota | |

| Animation Director: | Nobutake Ito | |

| Key Animation: | Nobutake Ito | Yasunori Miyazawa |

| Kanako Maru | Tatsuro Kawano | |

| Izumi Murakami | Tomomi Kawazuma | |

| Kei Masaki |

.png)