Remembering Fred Crippen: The Iconoclast Creator Of ‘Roger Ramjet’ Dies At 90

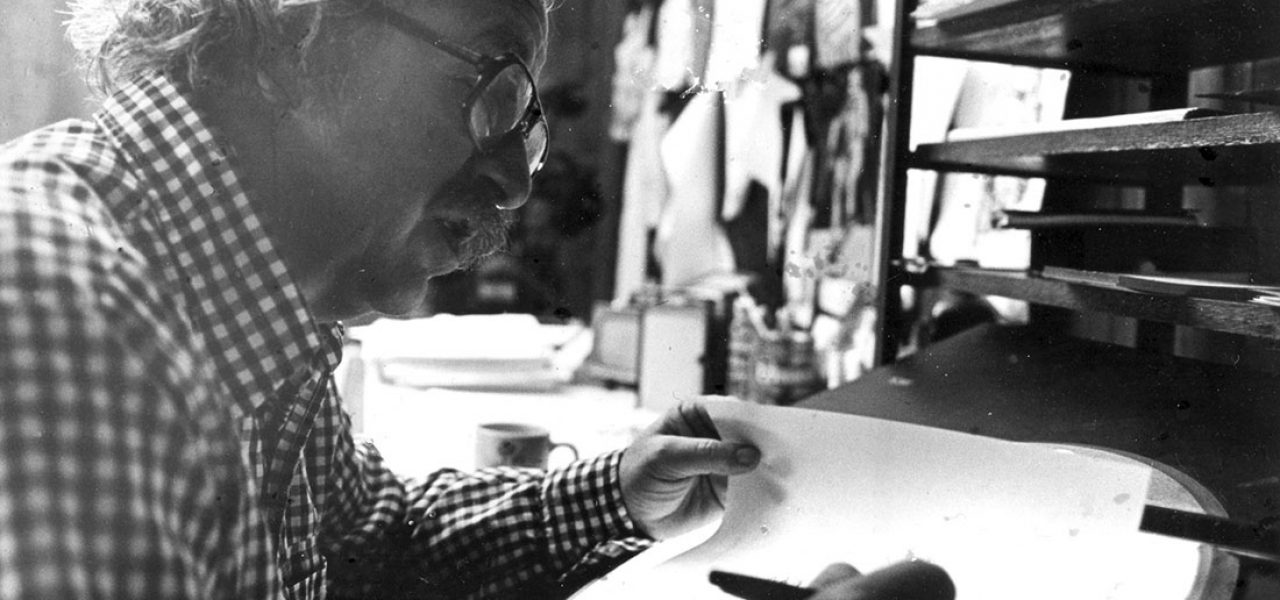

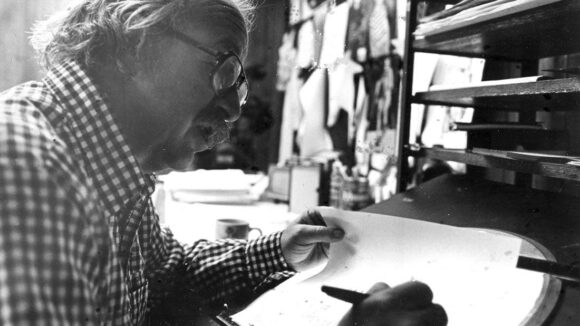

Fred Crippen, an iconoclast animator and director who played a key role in the development of limited tv animation, created the Sixties cult animated series Roger Ramjet, and owned Pantomime Pictures for over 50 years, died on March 22. He was 90.

Crippen began in the New York animation industry in the early-1950s, and was eventually hired by United Productions of America (UPA), the legendary studio that led the rebellion against the “Disney style” and ushered in a more stylistically diverse approach to commercial animation in the United States.

He eventually rebelled against the rebellers, pushing the stylization and minimalist animation that UPA was famous for to new extremes. His austere approach to animation, combined with an instinctive sense of design, led to his becoming the most prolific director on UPA’s The Boing Boing Show (1956), an important series in the history of early tv animation.

Crippen set out on his own around 1959, co-founding Pantomime Pictures, a studio that lasted for over 50 years, during which time he produced hundreds of advertising commercials, children’s films, television projects, film inserts, and other assorted animation projects.

Despite being firmly entrenched in the commercial animation world, Crippen had an indie mindset, with a make-it-up-as-he-went-along style of production. He often subverted traditional studio system procedures, animating many commercial projects on his own, and using quirky timing, staging, and cutting techniques. Crippen thought nothing of it to add a random camera move into the middle of a shot, or insert a derpy facial expression a couple frames before a cut – he proved that limited animation doesn’t have to be boring or mechanical as long as the animator is having fun and keeps experimenting.

His unconventional approach was perhaps best reflected in the rapid-fire Cold War-era satire Roger Ramjet (1965). The ultra-low budget series defied the conventional production pattern for tv animation by producing a locked audio track, complete with sound effects, at the beginning of production before the artwork was produced. The show’s directors then took a Mad Libs-approach to the artwork, filling up the episodes with the craziest things they could think of, so long as it matched the timing of the audio track. Adding to the mayhem, the design of the characters varied from episode to episode – something that Crippen encouraged. He deplored what he described as an “on-model fetish” in conventional animation pipelines and encouraged his crew to draw characters with their own personal flair.

I had the good fortune of knowing Fred for a period of time in the 2000s, and organized a couple of retrospectives around his work, including one at the Ottawa International Animation Festival. He was a wonderfully quirky guy who worked in a wonderfully quirky retro-studio in Valley Village, near North Hollywood. One of the things that I fondly remember about him is how he was always quick to compliment himself after we watched any of his films, saying things like, “That’s a pretty good film, even if I did make it” or “If I hadn’t made that film, I’d be jealous of the person who did.” It never came across as arrogant, just a funny tic that made visits with him memorable.

He was a real one-of-a-kind character whose contributions to the art form still impact today’s tv productions even if his name isn’t as widely known as it should be.

Below is a more detailed appreciation of Fred’s work that I wrote for a 2003 issue of ASIFA Magazine which offers more details about his life and work. (It has been lightly edited from its original publication.)

Fred Crippen: Independent in Hollywood

[published in “ASIFA Magazine,” autumn 2003]

Fred is showing me the animated sequence he directed for the Oscar-winning documentary Why Man Creates (1968) directed by Saul Bass. The five-minute sequence, designed by Bass associate Art Goodman and Crippen, is a supremely elegant account of the evolution of man’s intelligence, all played out during one massively complex vertical camera pan. Afterwards, I ask him who the animators were on this project. “Just me,” he replies. “Just you,” I ask puzzled. “Yeah.” Then Fred starts talking about the technical difficulties of executing the pan.

It hardly should have come as a surprise. In a career that has spanned more than fifty years, Fred Crippen has been something of an anomaly in the Hollywood animation scene. He has frequently behaved more like an independent animator, shunning the compartmentalized nature of studio animation. The hands-on approach he’s taken to his work has meant that he has often been the sole director, designer and animator of projects, only hiring others to help out when the workload became too much for one artist to handle.

Writing about Fred Crippen is no walk in the park. For starters, how does one even introduce the man? The easy solution would be to preface his name with the words “Roger Ramjet creator” and discuss how he came up with one of the funniest cartoons ever to appear on television.

But where would that leave the other Crippens? The teacher Crippen who created hundreds of animated spots for Sesame Street and The Electric Company educating children about all manner of words, shapes and numbers? Or the modernist Fred Crippen who animated to the smooth West Coast jazz sounds of Shorty Rogers, Shelley Manne, and Howard Rumsey as a director and animator at UPA in the Fifties? Or the socially conscious Fred Crippen who created an iconic political ad for the Kennedy campaign in 1960 (embedded below) and directed the award-winning short film Oh Yeah! (1968) which featured two characters shouting ethnic slurs at one another? Or the commercial Fred Crippen whose studio Pantomime Pictures has produced hundreds of TV commercials.

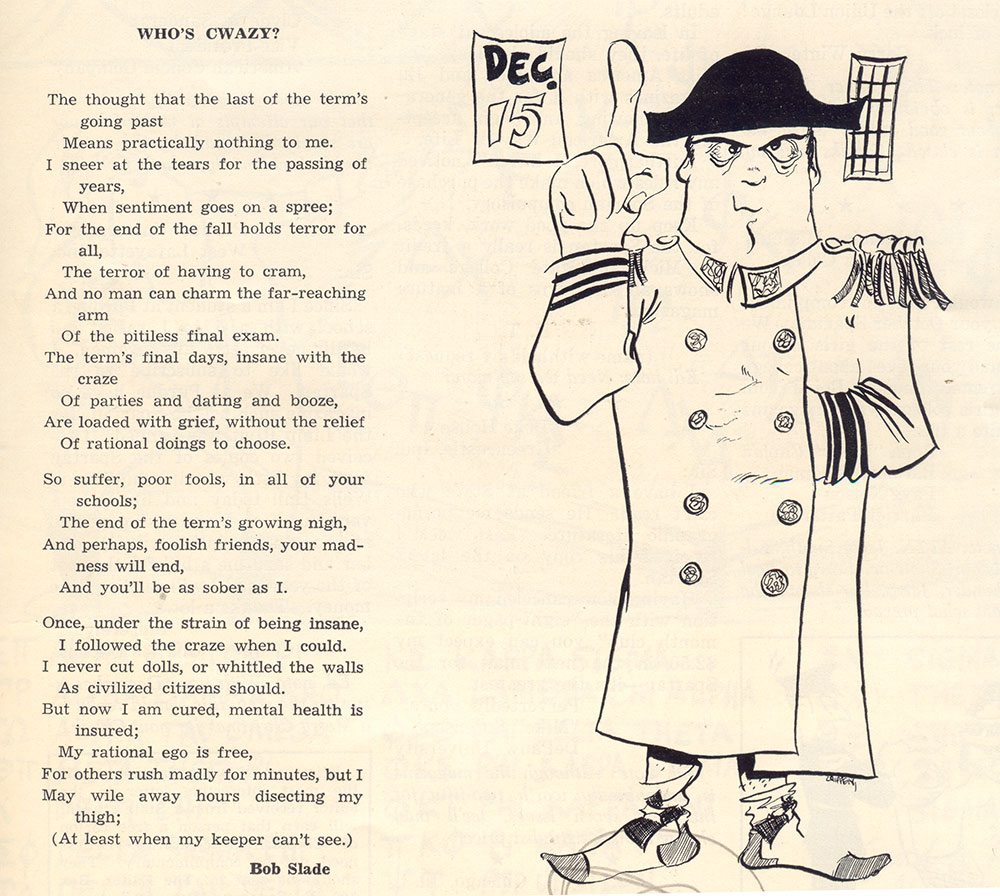

Animation wasn’t anywhere on Fred Crippen’s career radar while attending Michigan State University in the early Fifties. “I wanted to be another Jackson Pollock,” he recalls. After a stint as the art director of the college’s humor magazine The Spartan, he also considered becoming a New Yorker magazine cartoonist. His cover drawings and interior cartoons for the Spartan offer stylistic nods – spindly line quality, large noses, Picasso-esque abstractions – to top magazine cartoonists of the day like Saul Steinberg and Virgil Partch.

Animation first grabbed his attention in 1952. “At that time, I’d seen a UPA film, Rooty Toot Toot, and I was really impressed with that film,” he said. “It was a real departure from what animation had been doing, in style of animation, the design of the thing, it was really influenced by contemporary art. Because Disney and Warner Bros. and everybody weren’t doing much. Warner Bros. had gotten so into doing hurt gags; there was some funny stuff there but it was just one hurt gag after the other.”

After college, Fred landed a job illustrating sales presentations at Detroit industrial film producer Jam Handy. “They had an animation place upstairs and so I used to go up there and started hanging out because I was interested in UPA. I got to know Bill Bernal real well; [he] was a writer working there. He came out to Detroit from New York because things were slow.” When Bernal returned to New York, he called Crippen about a job opening at Shamus Culhane’s commercial studio and Fred made the move east. Following a short stint at Culhane’s, Bernal introduced Crippen to Gene Deitch who had just assumed the post of creative director at UPA’s commercial outfit in New York. Fred Crippen would now begin working at the studio responsible for Rooty Toot Toot.

In true unconventional UPA fashion, Fred was hired as a designer, bypassing the traditional animation studio entry position of assistant animator or some such subordinate position. “The studio was on 5th Ave, it was big time, almost right across the street from the Museum of Modern Art, and it was in a very fashionable part of New York.” The studio at this time was the undisputed leader in high-style TV commercials with a crew that included Gene Deitch, Cliff Roberts, Grim Natwick, Abe Liss, Chris Ishii, Jack Goodford and numerous other top talents.

During one slow period at the studio when Fred Crippen was in danger of being laid off, he came up with a creative solution. “So I said, ‘Well, if you’re going to lay me off, I’ll paint the studio for you,’ so there was a month there where I painted [the walls of] the entire studio.” He soon returned to animation work and worked for a while as an assistant animator to Duane Crowther. He remembers the day when Bobe Cannon, Herb Klynn, and T. Hee came out to visit the NY studio from UPA-LA. Both parties made an impression on each other. Fred was taken aback by the extravagant clothes the West Coast artists wore – “very California – yellow pants, orange shirts – especially T. Hee” – and the trio was impressed by Fred’s drawings, so much so that they invited him to move to Los Angeles to work on the new Boing Boing TV series.

Upon arrival in Los Angeles, Fred teamed up with Ernie Pintoff and Jimmy Murakami, two other recent UPA arrivals whose enthusiasm to experiment graphically made up for their lack of professional experience. Fred dubs the trio “the dark side animators.” Experimental animator John Whitney also joined their unit and together they produced nearly twenty films in just over a year, more than any other unit working on the Boing Boing TV series.

This burst of creativity could have only happened at UPA, a supportive environment where the only criticism Fred says he received from upper management was when Bobe Cannon suggested Fred make his characters’ noses a bit less gargantuan. Some of the classics that emerged from their unit include Three Horned Flink, The Little Boy Who Ran Away, Fight on for Old, Aquarium, and Blues Pattern.

“We were knocking out about three a month. Of course, they didn’t have a lot of animation in them, but we were just pounding them out like mad,” Crippen recalls.

He remembers once when veteran animator Rudy Larriva came over to look at his exposure sheets and shaking his head at the sparse animation timing before walking away. Fred continued animating and directing tv commercials and shorts (including the Oscar-nominated Trees and Jamaica Daddy), before deciding to set out on his own in 1959 by forming a commercial studio, Pantomime Pictures, with UPA alumni John Marshall and Jack Heiter. In the course of a few years, Fred became the sole owner of the studio, and was well on his way to a long career as an independent commercial producer.

Besides the routine dealings with ad agencies, Pantomime found alternative methods of soliciting work in the early years. “There was a friend of mine I went to college with, Dick Reed, who was a salesman and he was out hustling the work. He had a lot of guts because anybody that was a movie person or anybody that might have work, he would just go up to them. And we did work for Ernie Kovacs and Jerry Lewis because of this. He ran into Edie Adams [Kovacs’ wife] at a bar down here. He was pretty good looking, and of course she was too, so she probably accepted him more. And he just sat down and started talking to her and told her what we did, and she says, ‘Well, I’ll talk to Ernie.’ So then I did some bits of work with him.” (Below is an animated segment directed by Fred Crippen and designed by Saul Bass and Art Goodman from Stan Freberg Presents The Chun King Chow Mein Hour: Salute to the Chinese New Year (February 4, 1962). The soundtrack is from Freberg’s album “Stan Freberg Presents The United States Of America”.)

In the mid-’60s, Ken Snyder, head of the Needham, Louis, Brorby agency and a supporter of Pantomime Pictures, sold an animated series to two sponsors: Tootsie Roll and AMF (an industrial manufacturer known best for their bowling alley equipment). Out of this evolved Roger Ramjet, a tv series which premiered in 1965.

Fred’s original concept for the series was intended as “a whole take-off on the military complex… it was really satirizing the United States because this is a super-military country and Roger Ramjet was a buffoon military pilot with these kids who are wise guys.” In its final form, the cartoon not only satirizes the government and military, but also musicians, actors, and anybody else it could get its hands on.

“On Ramjet, I picked my friends and the guys that I knew were thinking like I did – Bob Kurtz, Sam Weiss, Joe Bruno. And there was no Disney types in there at all. I always liked the freedom that UPA gave me, so I’d just give them a record and said you design the characters and do a storyboard. I’ll check it and then you go ahead and do it.”

The Ramjet series was minimalist to the core, as much out of necessity (the budgets were a meager $4,500 for each five-minute segment) as being a reflection of Crippen’s unorthodox animation training at UPA. Crippen never makes any attempt to hide the fact that the cartoon was done on a limited budget. When characters are punched in fight sequences, title cards pop up that read “Hurt,” “Smash,” “Ouch,” “Hurt Again,” etc. in place of animation. Such creative flourishes are why Roger Ramjet remains as fresh and clever today as when it first premiered nearly forty years ago.

The soundtracks are another integral element of the series and the breathless delivery of the voice actors was no mistake, Crippen says. “The writers [Jim Thurman and Gene Moss] were writing twelve minutes of dialogue and trying to record it in five minutes. At first they would try to do it and they couldn’t. So finally, ‘Well, let’s just go ahead and record everything and we’ll edit it down,’ and that’s the reason they got so sharp. They just recorded a lot [of material].”

While Ramjet lasted only one season of production — resulting in 156 five-minute episodes — plenty of other work followed, much of it handled by Fred himself, with a healthy crew of free-lancers taking care of the rest.

The work included his long association with Sesame Street beginning in the late-’60s, two more TV series based on toy properties, Hot Wheels and Sky Hawks, odd bits like an insert for a Steve Martin television special and a series of animated limericks for The Playboy Channel, award-winning short films about racism (Oh Yeah!, embedded below), morticians (The Death Hour) and weapons of mass destruction (Condition of Man), and too many commercials to catalog, including the classic long-running series of outlandish ads for L.A.-based hardware store, National Lumber, featuring Shorty & Cheap Chicken.

In recent years, Fred has taught animation (currently at The Art Institute of Orange County) and occasionally worked in the industry, taking on timing and slugging gigs on tv series, but his true love remains the projects where he is involved from beginning to end. His most recent film, still in production, features a professor who instructs viewers on the numerous ways to use the “f”-word.

“I think I got a knack for getting the message across in a very strong way,” Crippen sums up. While it’s true that Fred can direct, design, animate and do just about everything else required in animation production, his most unique ability is knowing how to utilize all of the above skills to communicate a strong visual message to audiences. Throughout Fred Crippen’s remarkable animation career, whether it has been teaching children the difference between a cat’s meow and a dog’s bark, selling banking services and tires, or putting across a political viewpoint, he has consistently achieved a harmonious unity between form and content… and all while drawing really big noses.

.png)