Home Sweet Home? — Matea Radic Takes Us To ‘Paradaïz’

In Paradaïz, a new short from emerging filmmaker Matea Radic, the Canadian protagonist (Radic’s animated stand-in) returns to a home (Sarajevo) left long ago.

During her visit, past and present — nostalgia, history, and reality — collide. Going home, it turns out, is not so easy. It’s layered with complexities, as imaginings and longings clash with harsher truths. The home she left is not the home she returns to, and it can never be more than a figment of memory. And while Radic’s story is unique and deeply personal, this complexity — and often disappointment — of revisiting special places from the past is broadly relatable. Who hasn’t taken a drive to see their childhood home, school, or grandparents’ place?

Matea Radic’s story of return begins with departure. Asked when she left Sarajevo for Canada — and what the city was like at that moment — Radic answers with a memory that still burns bright.

“We left in late June of 1992. The city was under full siege, and we had been sleeping in a bomb shelter after the mini market on the corner of our street was bombed. I remember the night of that bombing vividly. The sky was a perfect indigo blue, and the flames from the burning building created a rainfall of orange embers. My dad carried me in his arms as he ran toward the shelter, and my eyes were glued to the night-sky light spectacle.”

They spent weeks sleeping underground. Then a rumor threaded through the shelter: “My parents had heard… that there was one last bus taking women and children out of the city the following day. So, they decided that my mom and I should take the opportunity to get out. After leaving the city, we spent a few months in Trpanj, Croatia, while we waited on paperwork to come to Canada.”

That trajectory — Sarajevo to Trpanj to Canada — is a clean line on paper, but in a child’s body it registered as fracture and survival. Radic would carry that split for decades. When asked if the recent trip was her first time back, she doesn’t elaborate; there’s no need. “Yes, first time back in 25 years.”

The homecoming began not on the ground but in the air, with a single image that wouldn’t let go.

“While the plane was descending toward Sarajevo, I was looking out the window at the rolling hills going by, and suddenly a fear came over me that the war could start again.” The reflex was automatic, half prayer, half magic: “I started having magical thoughts of pulling up the lush green hill as if it were a blanket and hiding underneath. That image burned itself into my mind’s eye and kept popping up, so I knew I had to follow it.” The hill-as-blanket — both shelter and shield — became the first brick in Paradaïz, a film that braids the city she left with the self she left behind.

The question of how to show past and present — how to let the child and the adult share the frame — wasn’t theoretical. It was personal. “I’ve always felt like my younger self was left behind, that I had to forget her in order to survive in the new world I found myself in,” Radic says. As the story started writing itself, a direction emerged: go back and take her hand. “It became clear that I was heading back to rescue her. I wanted and still want to be her again.”

Objects helped her map that inward journey. Cigarettes, for one, are everywhere in Sarajevo, as common as labored breathing. “Cigarettes are very much part of the culture in Sarajevo. It feels like everyone is smoking all the time. People smoke in the streets, in cafés and clubs.”

The cigarette is an object and a sign: omnipresent, performative, familiar. “The act of smoking has been around me my whole life, so I naturally became attracted to the cigarette as an object and symbol. And no offense, but it also looks cool as heck.”

During the siege, Radic and her cousin Veronika made their own out of paper and pretended to smoke “like the adults.” In the film, the cigarette glows with all that history — childhood mimicry, adult ritual, the everyday haze that softens hard edges.

Then there is the tomato, paradajz in Bosnian, whose sound drifts toward “paradise” in English. The slant rhyme opened a door. “The tomato is more of an absurd symbol. The word paradajz means ‘tomato’ in Bosnian, and other languages, too, but it sounds like the English word ‘paradise.’ It made me think about language and the space between words and their meanings, which then reminded me of my own in-betweenness.”

She recognizes herself in that gap. “How I’ve always felt like I didn’t belong there, and I don’t really belong here. There’s this term, ‘third culture kid,’ which is when a kid grows up in a different culture than their parents. And many kids who experience this create their own in-between worlds.”

Paradaïz is one such world — tender and absurd, a place where a tomato becomes a threshold. “I made up this world where a tomato symbolizes the pain you must go through to get to peace—a pain that I put on ice until I was ready to confront it.”

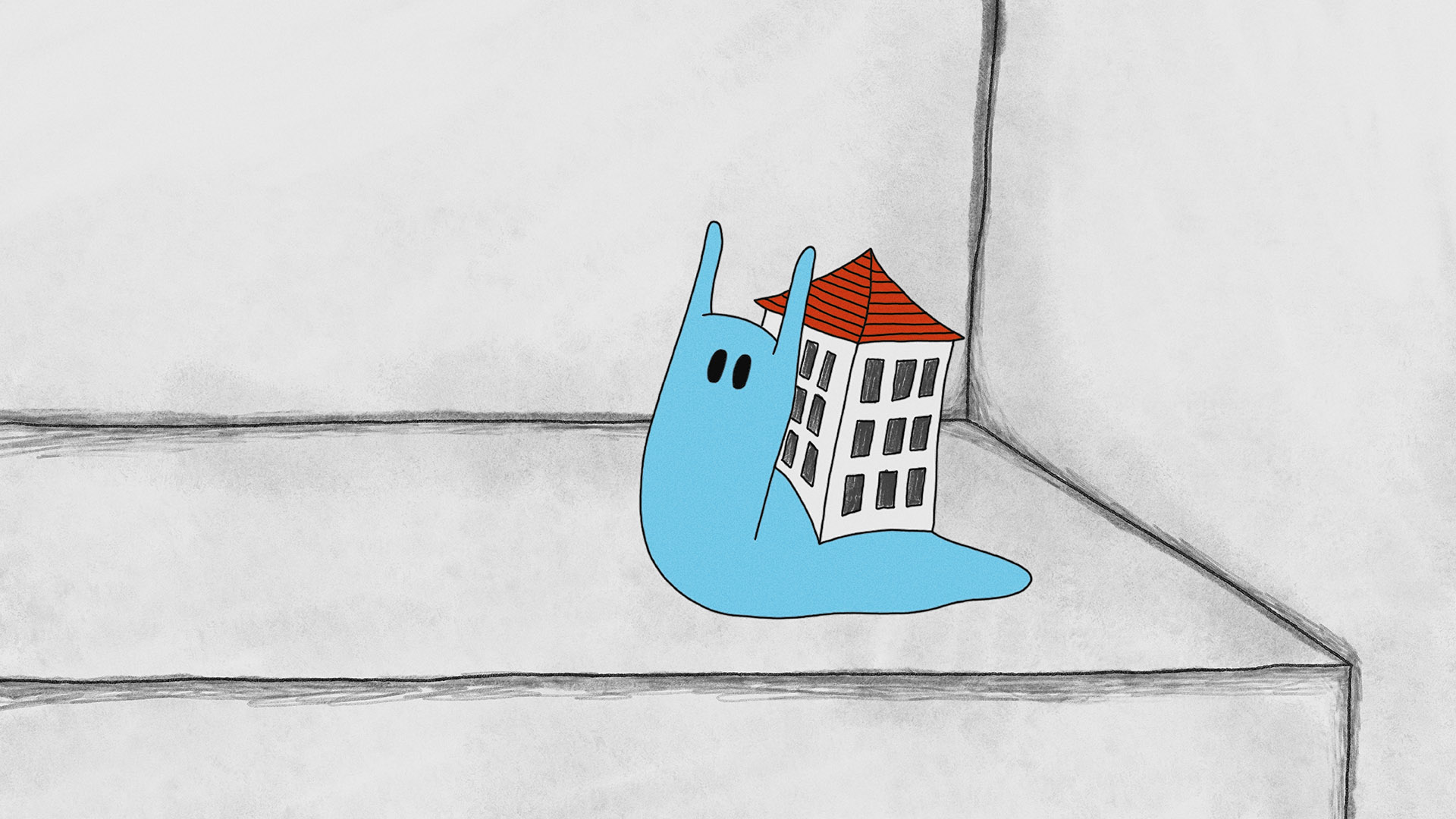

Another image arrived by accident after a rain: snails everywhere — slow, shining, innumerable. “I remember it rained one day while I was visiting Sarajevo, and I went out for a walk shortly after it stopped. I noticed a snail on the sidewalk, then another, then 10 more, then 100 more. They were everywhere.” Some had been crushed; others kept inching forward.

“I had to tiptoe around them so as not to squish any myself.” The metaphor wrote itself: “There’s a parallel between these snails with homes on their backs and many without, squashed on the ground or slowly moving toward safety, and us back then, running toward safety — to bomb shelters, or tunnels, or buses. And the many who were injured or killed.”

Formally, Paradaïz lives where documentation meets sensation. Radic grounds the story with actual photographs and lets animation carry the weather system of feeling. “It helped bridge my external reality with my internal feelings. The old photographs helped to ground the stylized world in reality — like, this place is real and familiar and this really happened — while the animation speaks to how it felt.” The photographs insist on facts while the drawn line can bend time, fold memory, and allow the adult to meet the child without explanation.

For all the heaviness the film holds, Radic’s return wasn’t defined by shock or estrangement. It was defined by recognition. “I think I was most surprised by how familiar it felt,” she says. “I was only six when we left, and returning 25 years later it still felt like home, but smaller.”

The body carries its own map; the palate, too. “People’s faces were familiar, and the ice cream tasted just like it did back then. The ice cream is really, really good in Sarajevo. Better than any other ice cream I’ve ever had. For real.” It’s an unexpected refrain, and an accurate one: grief and pleasure are not opposites; they arrive together.

The project’s shape changed as it was drawn. Early on, Radic imagined “dark shadow monsters” stalking her across scenes — a personification of dread and the faceless machinery of war. But as she storyboarded, those figures began to fall away. “In my original story, I had written in these dark shadow monsters that followed me throughout the film, but as I was storyboarding, I slowly edited them out because I didn’t want it to be about them; rather, I wanted to focus on my own internal journey.”

The decision reorients the camera from spectacle to interiority. “There are so many stories written about the war machine,” she says. Paradaïz chooses the other side: daily life and the residue it leaves. “I really wanted to show the other side of war and trauma, and how it never really leaves our bones, even years after the events occur.”

Threaded end to end, Radic’s images form a linear path that still honors the way memory loops. A child looks up at an indigo sky raining embers; a young woman peers out an airplane window and imagines a hill drawn up like a blanket; an artist assembles photographs and drawings so the past and present can sit in the same light. Cigarettes glow in doorways; a tomato carries both a joke and a sting; snails inch forward between peril and shelter. The city is familiar and a little smaller. The ice cream is still the best she’s ever had.

What Paradaïz offers is not a thesis about war or a simple return to a fixed home. It’s a carefully built passage between a life interrupted and a life resumed — between the girl she feared she abandoned and the woman determined to bring her along.

And if the film’s title echoes that slant rhyme — paradajz, paradise — it’s because the destination isn’t a perfect place but a livable one. Between what happened and how it felt, Radic finds room enough for both selves to stand. In that space, Paradaïz becomes what she imagined on approach: a blanket lifted over the body, a temporary shelter, a way to rest without forgetting.

Paradaïz screens in competition at the Ottawa International Animation Festival, running Sept. 24–28.

.png)