“I’m Tired Of Films That Try To Be Clear To Everyone”: Mykyta Lyskov Speaks To Ukrainians First In ‘Kyiv Cake’

Kyiv Cake is the latest short from Mykyta (pronounced Nikita) Lyskov, the creator of 2019 festival darling Deep Love (Annecy, Clermont Ferrand). It recently won the Best Ukrainian Film award at the Kyiv International Short Film Festival (KISFF) and will screen at the upcoming Ottawa International Animation Festival.

The short begins with a deer trotting merrily along, belting out a 1990s-style dance track. Within minutes, the film shifts from absurd to devastating. A man wakes next to his wife. He turns the power on, already locked in combat with the money-sucking, time-measuring electricity meter. He brushes his teeth; toothpaste oozes out, striped like the Russian flag. He brushes anyway. A tooth falls out. There’s a child. There’s a fridge, mostly empty except for a single box of Kyiv Cake. Inside? A passport.

The wife wakes to find her husband at the window, his body morphing into that of a bird. The baby cries. The man flies away. The woman endures. The boy grows. And just when life seems like it can’t possibly get any harder… a missile obliterates their building. Defiant, the boy shouts those words first heard on Snake Island: “Russian warship, go fuck yourself!” Kyiv Cake is surreal, furious, absurd, funny, and tragic — sometimes all at once. And like the cake itself, it has layers.

The Kyiv cake isn’t just food. It’s memory, identity, survival, and irony wrapped in sugar. Lyskov explains the film’s name: “First of all, this is a really delicious cake that I regularly treat my friends to on my birthday. But if you delve into the symbolism… inside the box is not just a Ukrainian passport, but a passport for traveling abroad. It explains why the father flies away and returns with euro money. The film’s first title was Bird’s Milk, but Kyiv Cake felt right. It carries Ukraine in its name, which helps immerse the viewer from the very beginning.”

It’s also a sly nod to politics: former president Petro Poroshenko’s confectionery empire produces Kyiv cakes, and he signed the 2018 agreement with the EU that gave Ukrainians visa-free travel.

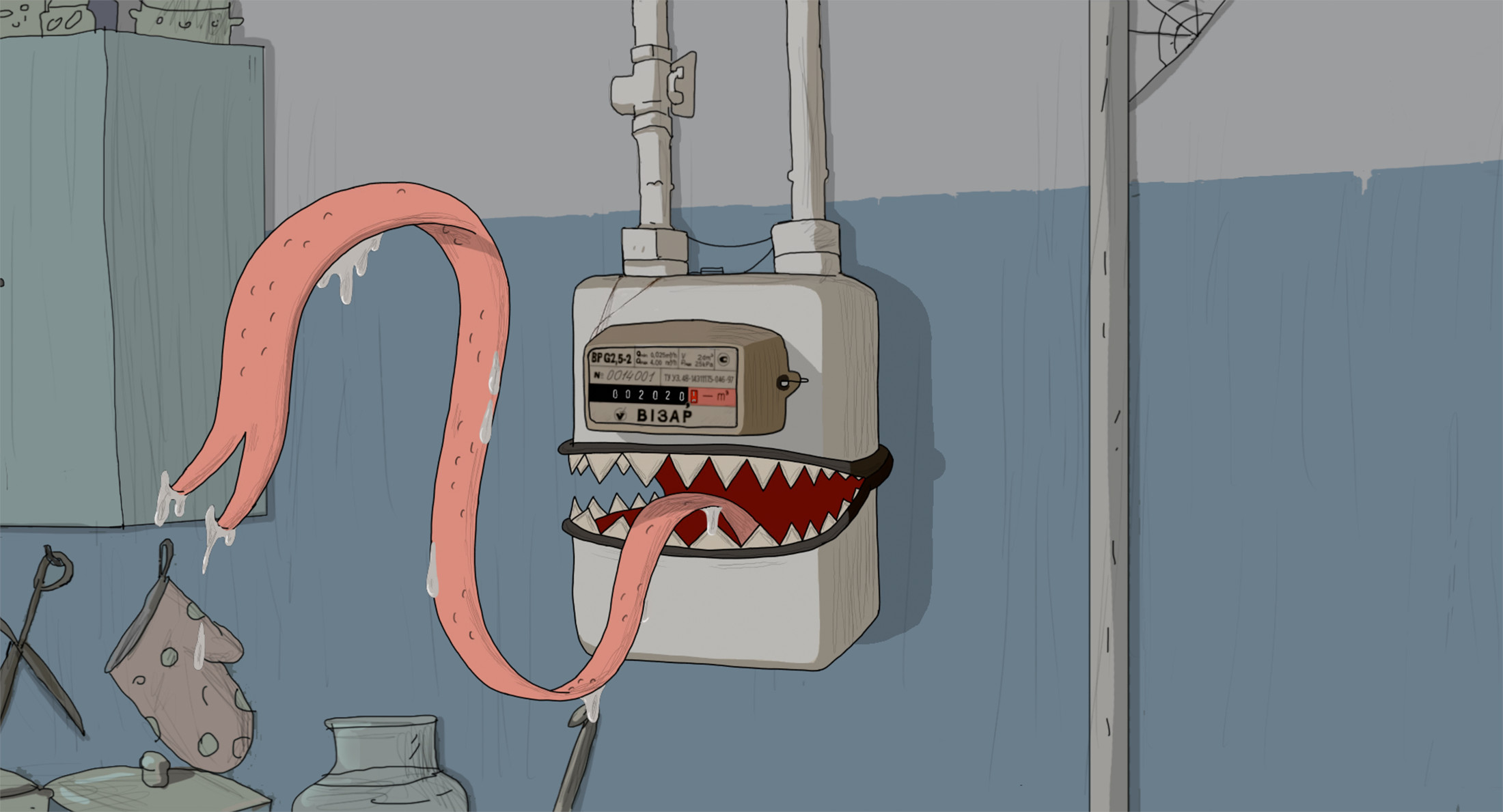

Lyskov doesn’t spoon-feed allegory; he throws viewers into a kaleidoscope of symbols — toothpaste that destroys teeth, McDonald’s boxes in an empty fridge, a father sprouting feathers, a tongue slithering out of an electricity meter.

“For Ukrainians, all the symbols are interpreted unambiguously. Carpets with deer hung in almost every family home in the ’90s. Toothpaste with a tricolor is a popular joke during the invasion — the Russian flag looks like Aquafresh. In 2014, Russia started a war by occupying Crimea and Donbas, so in the film the hero loses a tooth at that moment. I know foreign audiences won’t catch every reference, but I’m tired of films that try to be clear to everyone on the planet. I want to speak my language. I want to please the Ukrainian audience.” That’s the point: these aren’t tidy metaphors; they’re lived experiences, jokes, traumas, and domestic details twisted into dream logic.

The electricity meter keeps returning, ticking through years — 2014, 2018, 2022, nearly 2026 — before the screen goes black. “At the end of each month I have to check my electricity and gas meters and calculate what I owe,” Lyskov says. “I started to fear these devices, because the bills kept rising. Poor people often have huge debts for utilities. That’s why I portrayed the meters as antagonists — but also as markers of time. Ukrainians find this very funny. And to be honest, I’m afraid of 2026, because Russia’s aggression will only increase. Talk of a ceasefire is complete nonsense that only the idiot Trump can believe in.” Here, the banal collides with the existential: a domestic anxiety doubles as a doomsday clock.

There’s also a certain Estonian texture to Kyiv Cake — echoes of classic surreal animation that once smuggled truths past Soviet censors. The collaboration with Eesti Joonisfilm was both practical and personal.

“The collaboration began thanks to Olga and Priit Pärn. We communicated a lot in 2022, and Priit even drew Putin’s death for the animation jam Putler Kaput. I had a script ready, but Ukrainian cultural funds collapsed after the invasion. Olga and Priit suggested pitching to the Estonian Film Institute. Together with producer Kalev Tamm, we submitted the script online and it passed the selection. The whole team was Estonian; only the composer Anton Baibakov and I were Ukrainian. The producer gave me complete freedom. It didn’t change my creative process, though technically I had to install legal TVPaint software — before, I used hacked Adobe. And the sound director, Horret Kuus, created a brilliant soundscape. Estonia’s surreal tradition influenced me, yes, but so did Armenian director Robert Sahakyants.”

Despite the tragedy, Kyiv Cake is full of absurd humor: a singing deer, sly exaggerations of everyday life, grotesque flourishes that make you laugh while your stomach twists. “Laughter really helps — it devalues fear,” Lyskov says. “It shows that there are still parallel ways of interpreting reality. The film is a collage of emotions; it can be funny and bitter, sad and optimistic at the same time.” Humor here isn’t escape; it’s defiance. To laugh at fear is to rob it of power, even as the missiles fall.

The story follows a family across years of absence, hunger, resistance, and inheritance. The father leaves — to fight, to work abroad, perhaps both — and the boy inherits not only his father’s silhouette but his spirit. Both father and son wear the traditional Cossack forelock, a hairstyle once nearly erased by Soviet rule. “This shows that even though the Soviet Union tried to erase our identity, it remained deep in our subconscious. That gave us the strength to resist such a great enemy as Russia,” Lyskov says. “For me, 2014 to 2025 is a time of awakening — of realizing what it means to be Ukrainian and returning to the roots.” Resilience isn’t just political here; it’s generational, passed down like memory, like a stubborn haircut.

A viewer looking for clean allegory will only find the film will wriggling out of their hands. Of all the images, the tongue emerging from the electricity meter is the most unsettling: grotesque, damp, impossible to pin down.

“For me, electricity and gas counters are symbols of poverty,” Lyskov says. “They keep people in constant tension and stress. At the same time, they show our alarming dependence on Russian energy sources.” Like a snake slithering out of the wall, the tongue embodies menace without fixed meaning. Corruption, occupation, hunger, despair — all of them, none of them. It’s the sort of thing you can’t unsee, like the Glovo couriers forever buzzing past you on bikes: the economy keeps moving, even when the ground is breaking.

Kyiv Cake was drawn under real threat. Lyskov lives in Dnipro, not quite a frontline city but close enough to feel the war daily. He worked on Kyiv Cake under that pressure. “I worked remotely with Estonian animators while living in Dnipro,” he says. “At night, my wife and I often woke up to explosions near our house, and my wife’s parents miraculously survived — a Russian rocket hit their home. The constant threat sobered me as an artist. I asked myself: if tomorrow I am gone, is what I’m drawing really what I want to leave behind? That state helped me be ruthless with my work.”

More than just a surreal short, Kyiv Cake is a chronicle of absurd survival, of laughter lodged in the throat, of families carrying memory forward. It is distinctly Ukrainian — layered, bitter, sweet, and stubborn. The cake hides a passport. The bird flies. The tooth falls. The missile strikes. The boy curses the warship. And still, absurdly, bitterly, people laugh. Everything will not necessarily be fine. But everything will be remembered.

.png)