What Is VR Good For? The Creators Of ‘Gymnasia’ Have Some Thoughts

Gymnasia is a new vr project by the award-winning folks at Clyde Henry (ie. Chris Lavis and Maciek Szczerbowski) who are probably best known for their Oscar-nominated, Madame Tutli-Putli (2007) and their adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s book, Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More to Life, produced by Spike Jonze.

A co-production between the National Film Board of Canada and Montreal-based immersive content shop, Felix and Paul Studios, Gymnasia premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival last April, and also showed at Annecy earlier this month.

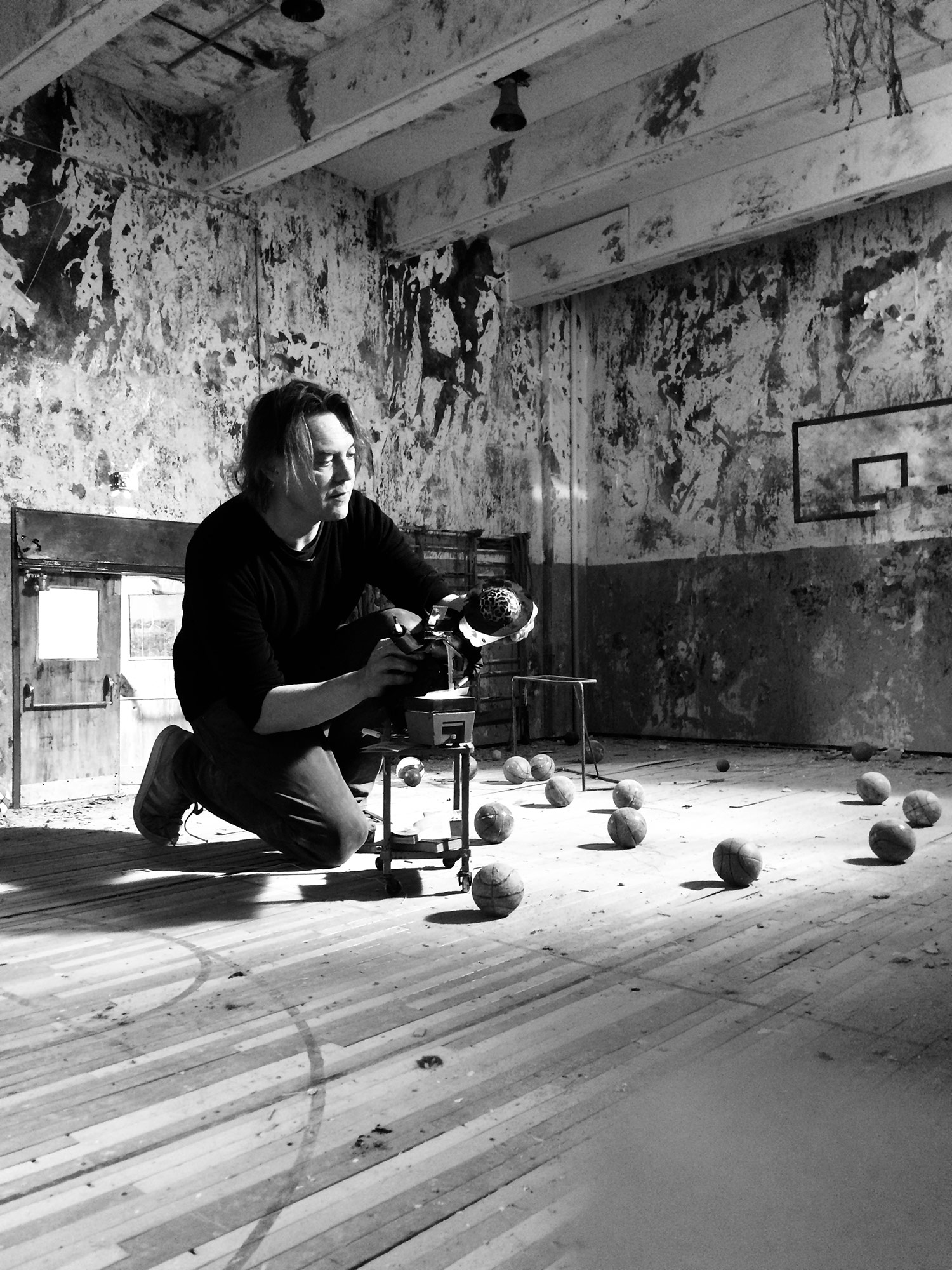

What struck me about this vr experience was that nothing really happens in a sense. We’re dropped into this rundown school gymnasium. We meet a couple of characters and that’s about it. And I don’t mean that as a critique of the work…it’s what makes it so great…it’s empowering the viewer in a sense…it’s up to you to determine what it all means…they just give you some universal (at least from a Western perspective) trigger points: old school gym, stage, basketballs, overhead projector. Watching Gymnasia is akin to having a dream…you’re in the midst of the familiar yet strange and fragmented place and then it just ends suddenly.

Cartoon Brew spoke with the two directors, Chris Lavis and Maciek Szczerbowski, in their Montreal studio, about potential avenues of exploration in virtual reality, why sound is integral in the medium, and why conventional storytelling is “almost impossible” in vr.

Cartoon Brew: What came first? Did you set out wanting to do something in vr or did you have an idea that you thought would work well in vr?

Maciek Szczerbowski: I don’t think it was ever that deliberate. What happened was that we had meet the guys Felix and Paul Studios after we made the stereoscopic film, Couchmare (2013).

Chris Lavis: We met them on the stereo film circuit. They were getting into vr and we started talking with them about collaborating on a piece. It was an experiment called Strangers with Patrick Watson, which ended up being the first live-action vr in the universe. They didn’t know it yet but their technology was years ahead of Silicon Valley’s. So they had this jumpstart on the technology and took off and worked with NASA, Jurassic Park, LeBron James, Barack Obama, etc.… We did our own thing for five years and we came to them with the seed of an idea. We had an old idea that we wanted to do stop motion and vr.

Szczerbowski: There was something that came out of the experience with the Patrick Watson experiment where he looked at the camera at one point and in the 3d experience it was an unbelievably powerful moment. There was a powerful emotional connection with the subject, which was something totally other than when an actor looks into a camera during a movie.

Lavis: We thought that was a worthwhile basis for an experiment for stop motion and to see if a stop motion character you shared a space with could create that same intimacy as a human being, which is one of the powers of vr. We set out with that as a hypothesis without proof.

Szczerbowski: The second weird thing that happened during the Patrick piece was that as he’s playing piano and being casual, not acting, he lights a cigarette and takes a couple of drags and then puts the cigarette into a glass ashtray. It was filmed in 3d and 360. When we watched it weeks later in a non-smoking studio space, I swear I could smell the smoke when that happened. Something happened in my brain, on a Radiolab neurological level, where the brain was sufficiently fooled by the premise of this being a form of reality and recognized the reality of being six feet away from a burning cigarette. I thought this was cool and worth pursuing. So we wondered if we went into our dusty old sets, if we could by a careful orchestration and arrangement of objects and space and sort of poetics maybe [mak the viewer] smell that part of your childhood: the gymnasium you were in when you were 10 or 11, the weird sweat, the squeaks of the sneakers. Elementary school has a smell, so part of our hypothesis was, ‘Could we make you smell that?’

Cartoon Brew: It’s scratch and sniff to the next level!

Lavis: We could put gym socks under people’s noses while they’re watching it.

Szczerbowski: You’re right, gym socks or old sneakers!

Cartoon Brew: It’s all extended from filmmaker/showman, William Castle, who set up some cinema seats to shake during certain moments in one of his B-movie horror films. [Later on, Maciek waved an old sneaker around me as I was re-watching Gymnasia. I did not notice. Clearly, smellier sneakers are needed.]

Lavis: The other thing that’s interesting about the medium – cause you said you don’t like it and never thought about it much – we haven’t much either. People were recently talking about cinematic vr and how film is in trouble, but film is not in trouble. And one of the reasons is because nothing works in vr that works in film. Because you can’t edit, you can’t lead the viewer’s eye…so the art of montage is off the table. It’s not even the art of storytelling around the campfire because even then you will be compelled to look at the storyteller and if your eyes start to wander that storyteller will bring you back. They’ll notice – as they would in theater – that you’re being rude whereas in vr they have no idea. You could be sitting there in a room with Albert Einstein, but if you choose to look at the ceiling there’s nothing we can do about it. It’s a medium where you can’t punish people for looking in the wrong direction and that makes it really limited medium, and for storytelling, almost impossible. But for us, we’ve never been masters of that kind of storytelling anyway, so it’s kind of exciting.

Szczerbowski: It was a cool experience to not write a story.

Lavis: What’s great is that nobody can write a story. You can set out to make the most commercial vr, but there are no commercial tropes. You can’t make an action film or horror film in vr. It doesn’t work.

Szczerbowski: There’s also no group catharsis. You cannot experience this with people. You’re not raised by everyone’s laughter.

Lavis: And because there’s no montage, there’s not even a moment of catharsis. You can’t choose the moment of catharsis. People have them, as we’ve discovered, but in completely different moments. That’s if you’re going to have it. Some people watch it and experience nothing. But some people have had a more emotional experience than with anything we’ve ever done. It’s about the experience they had. It’s not something where they’ve been led.

Cartoon Brew: But you can map out every perspective they could possibly have in the vr experience.

Lavis: Yeah, but you can’t control when they look at something. You can control the space, and the sound design and the sound design probably has more say in story or catharsis than anything. And writing with Patrick Watson was a big part of it, making him part of the process.

Szczerbowski: Since we didn’t write it and so much came down to being in time with music and sound cues, Patrick ended up becoming a completely valid third writer – in whatever sense that means – because he determined when and how things happened and what gravitas they had. The basketball part was almost completely dictated by his recording session where he was like a live conductor of the kids bouncing the basketballs.

Lavis: Pat did the soundtrack before we animated anything. We got lucky. I think it’s the best thing Pat ever did for us.

Szczerbowski: The weird thing that we’ve discovered about music and sound in vr is that if you just watch Gymnasia without sound, time doesn’t exist. There’s no way to know that this moment came after that moment. You’re not in a real reality. Time works differently. Music is the only way to make you think time is moving forward.

Cartoon Brew: Why did you choose a school gym?

Szczerbowski: We do a lot of stuff with local French experimental theater. Their specialty is site-specific theater where the audience might be driven to a forest or a cemetery. They said to us that when you’re doing site-specific theater and you’re choosing that space, you’re choosing your main character. As a director you have to be careful to not come in with a full dialogue — maybe you have half of it, because you don’t want to drown out or ignore the other half of the information that will come from the space itself. Let the space speak.

Cartoon Brew: And that’s what happening in Gymnasia where the gym is in fact the protagonist…

Szczerbowski: Exactly. Our thinking was something like: Which part of our collective memory is the dustiest in your memory bank? We’ve been in classrooms since we were young. We’ve been on buses or walked in hallways. They’ve been refreshed so the old ones are gone, but the elementary school gym is a place we rarely revisit.

Lavis: …and if you do, the scale is completely different. They’re much smaller than you remember.

Szczerbowski: You’re not in sneakers…you didn’t just pee yourself. You’re not in that moment at all.

Cartoon Brew: I don’t recall the peeing part.

Lavis: (laughing) Neither do I.

Szczerbowski: (laughing) Oh, I do!

Lavis: They’re really interesting spaces. They’re ritual spaces. You go to Christmas concerts and magic show. You play in them. That’s why we put you on the stage so that you get that feeling of what it’s like to be a kid again.

Szczerbowski: It’s a kind of ceremonial space and it’s also a repository for an entire dimension of your childhood that you haven’t revisited. It’s also universal. I had that experience in Poland; Chris had it in Toronto. A large amount of people will likely feel it’s their gym.

Cartoon Brew: The experience really does on rely, say, a good viewer.

Szczerbowski: To some degree — even if you decide to stare at the corner ceiling I think there’s still some pleasure.

Lavis: You can’t control it and it’s really interesting. You end up with a ratio of every 10 people, two or three will be completely unmoored. One out of twenty gets really emotional and some of the rest think it’s really cool.

Szczerbowski: Some think it’s creepy.

Lavis: What’s kind of nice, unlike short films, is that you get a sovereign experience. You’re not in a program of 40 films. You have your little moment with this.

Szczerbowski: And if you go back a second time, it will be different. There’s no way you can have the same attention to the same things with the same timing.

Lavis: I wonder if people are more honest in their reaction at the moment they remove the headset, compared to watching a short film.

Szczerbowski: And how comfortable they feel being watched while they do this.

Cartoon Brew: There’s something almost anti-climactic about Gymnasia. I was waiting to be scared or shocked by something. So it’s like nothing happens yet it triggered all sort of memories and emotions for me.

Lavis: The end is abrupt because we ease in like a dream and end abruptly.

Cartoon Brew: When I thought about it after, I remembered my grandparents’ place being put up for sale. I remember the last night in this empty house. I’d be looking at a blank wall, but seeing all this stuff from the past come alive.

Szczerbowski: Memory doesn’t actually seem to be encoded in your head as much as in the places where they happen. When I go back to Poznan [in Poland], I remember stuff that I am unaware of here. It’s inaccessible to me. If I touch this fence or am next to that fountain, I remember that moment, but the memory is in that fountain or that fence. Otherwise I feel like I don’t have that memory anymore. And I think that’s something we were trying to do, to get your ‘access denied’ memories.

Cartoon Brew: I had hoped for some liberation for the viewer in vr, but most often I still feel I’m being led and controlled.

Lavis: Yes, but you know what’s interesting, Gymnasia has worked most powerfully on people who are cynical about vr or haven’t watched a lot. The hardcore people have big ideas about interactivity and being able to grab things.

Szczerbowski: And we didn’t want to do that. We wanted to have a sort of dream anxiety. You want to run, but you can’t. You want to stand but you can’t. Am I small in this space or big? These are questions you don’t normally ask yourself in real life. But the idea of not being able to move and having the whole scale fuckup of being in a puppet world, but on their terms, I think that contributed to that kind of dream anxiety.

Cartoon Brew: The little boy and the overhead lady character both look like standard old dolls.

Szczerbowski: There was something by the poet Rilke, who had this idea that there is a powerful relationship between us and dolls and puppets because we had them when we were babies, tiny children. It was through these objects that we invented our own adulthood. When you watch kids punishing a doll they are applying an authority that they don’t have with us, with their parents. This is their training ground for becoming an adult. Secondly, and I think this has a lot to do with the feeling of Gymnasia, is that kids at that young age use these primitive little dolls to invent death or their understanding of it. Sometimes our first understanding of death comes through puppets or dolls. You grow up and throw them away, but on some visceral level you associate them with childhood and death.

Lavis: And by the way that’s what Toy Story is about. Every single Toy Story is about death and aging.

Szczerbowski: This is the first film in animation where we didn’t make our own heads. Normally we sculpt our puppets. The idea here was that because of the Rilke theory, we didn’t want the puppet to be that boy; we wanted it to be everyone’s dumb old puppet, the most average puppet head you could find.

Cartoon Brew: I know you don’t like hearing that Gymnasia has a creepy feeling – at least initially. I didn’t feel that the second time around, but I think that those generic looking dolls do trigger a feeling of creepiness. I don’t have an abundance of childhood memories, but one of the strongest is an encounter with a kid’s Raggedy Ann doll. It scared the shit out of me. And the fact that some five decades later I still vividly recall this shows you how powerful that experience was.

Lavis: The creepiness is important. The director of Missing Link was saying something recently that puppets don’t have to be creepy. I think he was wrong, like epically wrong. And Cartoon Brew had the story about how Missing Link bombed and in the comments part there were some people saying, “Time to get back to Coraline.” And I also noticed that my nine-year-old daughter and her friends all talk about Coraline. It’s not just that it’s a scary film, it’s a growing classic. And at some point you have to admit that the medium has some of that DNA in it. It’s like stop motion has two siblings: one is Aardman and one is creepy. It doesn’t seem like you can go in between.

Cartoon Brew: Could you achieve what you wanted to do here within a short film?

Szczerbowski: No. We’d have to command the camera. We’d have to show you what’s behind and when do you show you that. I honestly feel that when I ask you sit down and watch this, it’s not like a film, it’s more like, “Hey Chris, did you see this garden behind the studio? Why don’t check it out and walk through it.” And that’s it. It’s over. And maybe you’ll want to go visit the garden again, and you can, but it won’t be the same because you’ll pay attention to something different. And that’s not the same thing with a film. A film is not a walk through the garden, but a walk through the garden is a cool experience. I think that’s where Pixar fucked it up. Story, story, story and nothing other than story. And vr is not for that.

Lavis: There’s an interesting essay from the guys from Oculus Story Studio about why story didn’t work in vr. They call it the “Swayze Effect.” He says that vr experience where characters are interacting and things are happening without the acknowledgement of your presence…

Szczerbowski: …makes you feel like Patrick Swayze in Ghost, where you’re like, “I’m right here! Why can’t you see me?” And people are walking past you and through you.

Lavis: And probably the most powerful moment in Gymnasia is when the boy looks at you. This is not the Swayze effect. It means you are on stage with the boy. Then you start asking yourself, “Why am I on stage?”

Cartoon Brew: Yeah, I thought the kid was going to knife me.

Szczerbowski: I remember your reaction verbatim. You suddenly said, “Whoa! Who the fuck is this guy!?”

Lavis: You’ve watched thousands of short films and you have probably never once said that. It also means, conversely, extreme limitations. If you have an idea for a short that involves story, for God’s sake don’t do it in vr.

.png)