Scratches, Ghost Noise, And 195 Million Views: The Retro Animation of Kazuya Kanehisa

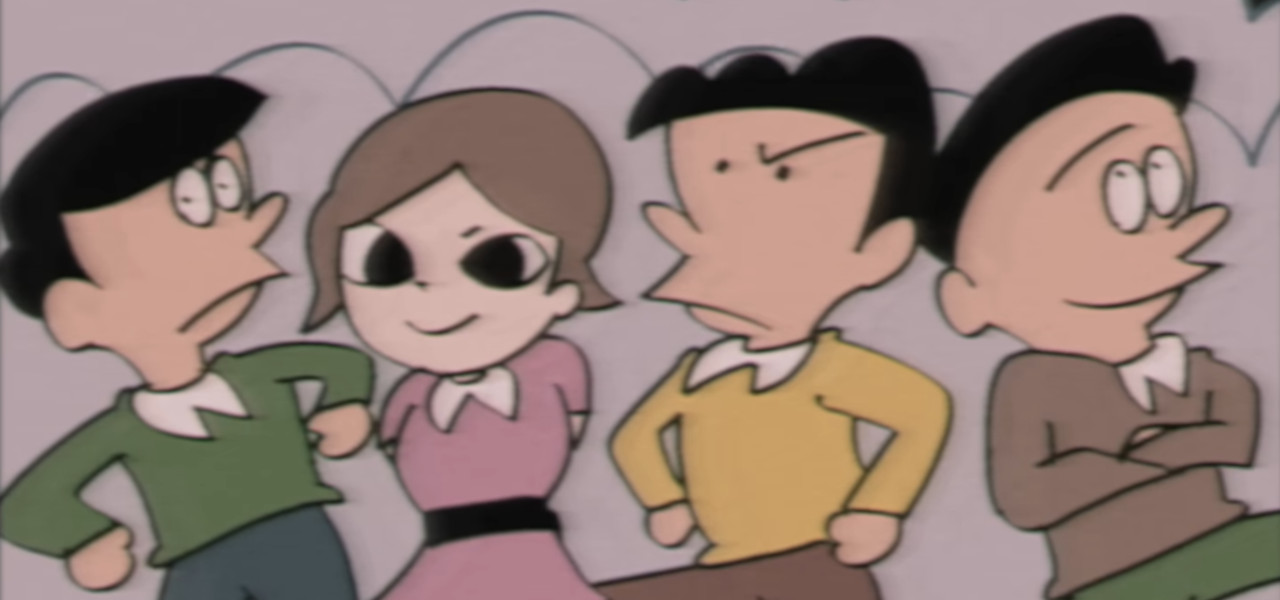

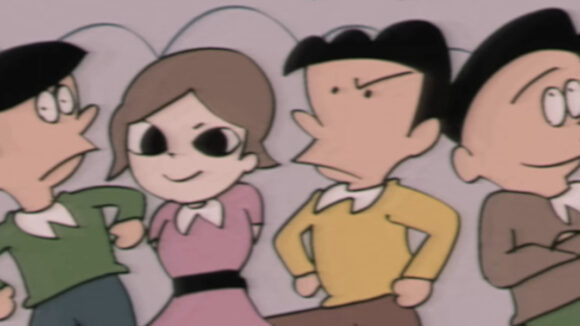

Japanese animator Kazuya Kanehisa has been quietly creating vibrant vintage designs that capture the essence of a lost animated VHS tape from the 1970s and 1980s. His old-school aesthetic, reminiscent of 1960s and 1970s Japanese comics and comic strips, is further enhanced by character movements that echo the style of Japanese animation from that era, with a touch of Fleischer Studios influence.

Alongside his writing work, which aims to “convey the fun of animation,” Kanehisa started producing videos in 2022. His shorts, which blend modern society with a nostalgic 1960s aesthetic, have been drawing a lot of attention online, most notably “Hai Yorokonde,” a music video that has racked up more than 200 million views.

For Kanehisa, though, the story begins much earlier than YouTube metrics.

“Since I gained consciousness, I remember being really intrigued and interested in animation,” he says. “So it’s really hard to say exactly when, because it was really whenever I kind of, like, gained consciousness.” He figures he was about three or four when the obsession took hold.

“I first became interested in the kind of classical animations of the US. For example, old Disney, as well as Fleischer Studios, MGM, and Hanna-Barbera. Things of the 1930s, 1940s.”

At home, the family watched public broadcasting, which added another layer. “There was a lot of kind of Golden Age animation as well as independent animation. For example, NHK’s Minna no Uta (Everybody’s Song). That was my introduction to independent animation.”

Despite the depth of his interest, he never took the art school path. “I’m completely self-taught,” he says. In high school, he considered Kyoto Seika, Tokyo University of the Arts, or Osaka University of Arts, but his club activities were full of people he felt were “much more talented” than he was at drawing. “So I thought, oh, maybe this isn’t the direction I want to go in.”

Instead, his curiosity shifted toward the industrial and historical side of the medium. “I was really interested in the animation history of the 1930s and 1940s of the US, as well as Japanese commercials from a time a little bit after that,” he explains. “So in high school, I was thinking of going into research on the industrial history of animation.”

He ended up at a regular university, studying literature and “analyzing film and representation through an anthropological perspective.”

What really shaped his way of seeing animation, though, wasn’t just the films themselves, but the materiality of film and video: the glitches and scratches most people try to avoid.

“I was very drawn to videotape and film itself as a material,” he says. His grandfather kept 8mm films at home, including home movies from Expo ’70 in Osaka. “This was a really damaged film with lots of lines in it, and those would appear on the screen as vertical lines. I would see how the material would be damaged and how that was projected. We would play with the projector, and my grandpa taught me how to use it.”

He learned to read the “wounds” on the film. “I knew that, for example, when I saw in certain films or certain videos, if there was a certain kind of damage, this is what it would look like on the film. And also seeing in the material itself how each picture would create a consecutive film when lined up together… seeing that in its materiality had a huge impact on me.”

He remembers how damage turned into something almost poetic. “The damage on the film would end up as almost like rain, you know, like so many vertical lines that it would appear as rain.”

That sensibility carried into the digital age. “If you look on YouTube, there’s a lot of old film that’s not only damaged, but the VHS of it is also not great quality. So it’s two layers of damage. But I really enjoy this kind of damaged aspect, and also this lens of the materiality of the medium itself.”

It might seem ironic, given his love of decayed media, that he’s firmly a child of the digital era. “I was born in 2001, so it’s basically the same year that Windows XP came out,” he says. “Since I was very young, there was always PC software to create animations, or there was a Nintendo DS game called Flipnote Studio. There was always easy access to animating.”

“The first time I made a very short animated video was in elementary school, and I think I made it with free Windows software. Since I was in middle school or elementary school, as far back as I can remember, I was already creating animations.”

His parents, though, were wary of the online world. “My parents didn’t want me to post anything online because they thought that would cause trouble, or that it would be the beginning of different problems,” he explains. His father, a high school teacher, had seen kids run into problems online: children talking to adults, miscommunication, a lack of media literacy. “So in the beginning, it was literally just me creating and not really sharing it online, but directly with friends.”

It wasn’t until 2017 that he started writing about the history of animation on Twitter. His first actual video work appeared on YouTube in 2022.

Before “Hai Yorokonde” exploded, Kanehisa had already developed a small following with short “fake commercials.” “They were mostly commercials for things like Spotify, Netflix, the iPhone, these contemporary technologies or subscription-based services, but represented in the Showa era in monochrome,” he says. “It was more of a comical short video.” Some of those shorts hit view counts “maybe in the millions.”

Then came “Hai Yorokonde.” At the time of our conversation, the video sat at around 195 million views, numbers that would make most festival darlings seethe with envy. Kanehisa is under no illusions about what that actually means.

“With that particular music video, all of the revenue goes to the music label,” he says. “I only got the initial commission.” The video did open other doors, including animations for NHK’s children’s music program Minna no Uta, as well as a short bit for the preschool series The Wakey Show, but the YouTube money itself is modest. “Regarding the other videos on my channel, there is some ad revenue, but it’s still very small, because not every video is viral. Even those that are viral, I get maybe 10,000 to 20,000 yen monthly, which is not even maybe 100 US dollars.”

What’s more striking than the money is the sheer amount of work compressed into a very short time. “The video was completed in ten days,” he says. “Usually, maybe I take a month to do it. But for this one, I did the storyboard and character design in two days, then the drawing and layout in five days, and then I filmed it and did the After Effects work in two days. That was kind of a miracle.”

None of this would work if he were only skimming the surface of retro style. Kanehisa is a fanatic. “I think there are about 1,000 episodes, but I’ve seen all of the episodes of Looney Tunes.” He’s also watched most of the works from Mushi Production and regularly visited commercial archives at AD Museum Tokyo (Minato-ku) and the Broadcast Library (Naka-ku, Yokohama), which archives Japanese commercials from the 1960s. “There’s a public viewing booth that you can go to, and I would always go there and watch all of them.”

He’s drawn not just to Hanna-Barbera minimalism, but to UPA and John Hubley, and to a broader world of graphic wit, like the works of Saul Steinberg, James Thurber, and Japanese animators such as Yoji Kuri.

As a kid, he was just as fascinated by music as by pictures, and that naturally pushed him toward works where movement and rhythm mattered more than conventional story. “I really liked mediums that weren’t really reliant on the narrative itself,” he says. “I felt like the movement, the repetitive movements of animation, were more primitive. I remember being really excited as a child by the fact that moving pictures were just very interesting, and they showed this kind of joy and happiness.”

When he recreates a certain era, he doesn’t just copy the surface. He mentally reconstructs the entire chain. “Usually, I pull from the songs I listen to and then imagine a motif,” he says. “But when I do that, there are a lot of steps. For example, when I think about how to create the effect in After Effects, it’s like, okay, there’s 16mm film, and maybe that’s Kodachrome. If it’s Kodachrome, then it’ll have a more sepia or reddish color. Then if you add the subtitles, which are very much a 1960s–70s thing, those would be added after, so they’ll look like this. Then it’ll be through television, and that’ll also look different because it’s particularly through a cathode ray tube. All of those steps I think about and try to negotiate within myself to create that kind of effect.”

For all his control over style, he hasn’t yet done a narrative short. “That’s actually one of the things that I’m looking to kind of confront,” he admits. He worries, though, that adding a more traditional story might limit what he wants to explore in animation. Instead, he’s drawn to the idea of an alternative history: “a sort of mockumentary, a fake fictional mockumentary about the history of animation… maybe a kind of 1960s animation and how it was being created, how it was organized, and the backstory of it. It would be a fictional setting, a fictional history of a kind of 1960s, 1970s animation, showing the first time it was aired and the process behind it.”

If his work feels like a love letter to old media, his view of the current media landscape is more cautious. In Japan over the past five or six years, he’s watched independent animators in their teens and twenties get recruited by record labels to make music videos. “There’s this sort of style that’s emerging there within the younger generation,” he says. Unlike festival films, which are made for audiences already exposed to animation, these works are aimed at Twitter and other social media, where most viewers aren’t animation people at all. For labels, it’s cheap. “They can commission artists for a much cheaper price than studios, get viral or popular artists, and have their music talked about for a much cheaper price.”

The dynamic feeds into a dependence on attention. A few years back, the hashtag indie anime was a space where young, amateur animators shared diverse, idiosyncratic work. “It used to be for sharing very different, unique work,” he says. “Now it’s really about what will be viral, what will gain popularity, what will receive attention. When there’s a popular animation artist and a certain style that has a tendency to be popular, everybody gravitates toward that and starts copying it. Something that was supposed to be about emerging artists sharing their distinct style has become more about attention-seeking and what’s going to get more views and connect to jobs.”

YouTube itself can feel more intimidating than festivals. “Getting your animation judged by people who understand animation is like a critique,” he says. “But when you get comments from all over the world, the trolls literally… it’s a very different kind of fear that’s unlocked there. Most of the comments fall into two types of emptiness: people who say, ‘Oh, this is great’ to everything, or people who say, ‘This is stealing from this other artist,’ ‘This is just a copy.’ Ninety percent of the comments are nonsense, empty comments.”

Maybe that’s where festivals still have a role, as slower spaces where dialogue can happen and the work isn’t devoured at meme speed. Kanehisa has begun edging toward that world, submitting his music video to Hiroshima and thinking seriously about how his work might sit in a theatre, away from the algorithm.

For now, though, Kanehisa remains a kind of glitch collector, someone who understands that what one generation saw as a flaw, scratched prints, warped VHS, unstable colors, can become another generation’s texture, their diamond.

Pictured at top: “Hai Yorokonde” / Kocchi no Kento MV

.png)