Stains On Silence – Ryo Orikasa’s Animation Word Plays

Ryo Orikasa is quickly becoming one of the great poets of animation. His works – from early pieces like Writings Fly Away and Echo Chamber, and the music video The State of Things, to the trilogy of award winners Datum Point, Miserable Miracle, and his latest, The Graffiti – all explore literature and the beauty and fragility of the written word. In films like Miserable Miracle and Writings Fly Away, the text itself becomes a character, dancing and darting, forming and collapsing on the screen.

Orikasa’s road to animation was, not surprisingly, unconventional. It wasn’t until university, when he was about eighteen, that he really encountered the art form. He found an article in a manga magazine that introduced the work of Czech animator Jan Švankmajer. “There was a still from one of his films, and I was immediately drawn to it. I bought a DVD of his work around 2005, and I still feel his influence very strongly.”

Orikasa was especially attracted to the earlier films from the 1960s to 1980s, like The House of Usher, based on Edgar Allan Poe. “He used literature very directly—Edgar Allan Poe, Lewis Carroll—and the way he referenced and transformed literary works into animation was really inspiring for me,” Orikasa says. “Up to that point, I hadn’t seen much animation at all, but I read a lot of literature. So when I finally found Švankmajer, it felt like a bridge between what I was already interested in—books—and this new territory of animation.”

During his third year at university, Orikasa started attending film and video classes at Image Forum. “I studied at a university in Ibaraki Prefecture, about two hours from Tokyo. In my third year there, I started attending classes at Image Forum in Shibuya—a kind of informal school for experimental film and video. At Image Forum I took workshops with different people, including Nobuhiro Aihara. After graduating from Ibaraki University, I entered Tokyo University of the Arts in 2009.”

With Orikasa’s student film, Writings Fly Away (Scripta volant), his voice is already there, especially his fascination with text and literature. Orikasa traces that focus back through his early work. “At some point I realized, ‘Ah, my interest is really in writing,’ and that this was something I wanted to pursue inside animation.”

Writings Fly Away is loosely based on Oscar Wilde’s story, The Happy Prince. “There’s a famous story that when he was nine years old Jorge Luis Borges translated Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince from English into Spanish,” says Orikasa. “The translation was so good that it was published in the newspaper. People suspected his father must have done it, but it was really Borges himself.”

The Happy Prince is about a statue that gives away its eyes to the townspeople. Borges did this translation as a child, and it became his first published work. “It feels miraculous that someone who would later lose his vision began his literary life by translating a story about eyes and sacrifice. That paradox, that strange symmetry, became the inspiration for Writings Fly Away. The movement from clear letters to blurred, fragmented text in the film is very much tied to that blindness.”

In the film, lines appear across the page as they are spoken by the narrator, each new line erasing the previous one. Soon, the letters begin to dance across the frame. The word “tears” cries black on the frame. The word “swallow” sprouts wings and flies. With each new page the words become more abstract and erratic, eschewing the orderly left-to-right progression, sometimes appearing bunched together in corners of the frame. The text becomes increasingly abstract, taken over by pictures. It might be an homage to Borges – it is a story about not having eyes, after all – but Orikasa’s interpretation also inserts his voice as a visual, experimental artist.

The shift from drawn work to clay in Datum Point (2015) came partly from Švankmajer. “Looking back, I think Švankmajer’s House of Usher, especially his use of clay, did influence me,” he says. Datum Point is based on the work of Japanese poet Yoshiro Ishihara. “He once wrote that writing a poem is like kneading clay. There’s a very physical resistance—you have to push through it. That idea of kneading, of wrestling with a lump of language, really stayed with me. Writing felt like a material struggle, and clay gave me a way to embody that in animation.”

Datum Point (2015) is a calm, Zen clay animation that captures the serenity of the sea, the soothing rush of the waves, the Heraclitean reminder that all is in motion, never the same. Waves of clay rush across the screen in different directions, forming different shapes before vanishing beyond our sight lines. They move fast, without pause, yet there’s no fear: it’s a hypnotic, almost soothing aggression. Words begin to form in the waves. Everything gathers, as though in search of a form, but the formlessness – the urgent rush for the form – is the form itself. Like identity, there’s no fixed state; it’s a fluid, constantly shifting process. The drone of Shun Owada’s soundscape lulls us along the way.

Silence, or something close to it, is crucial to the film. “When I read Ishihara’s original poems, I simply didn’t ‘hear’ anything,” Orikasa says. “No voice came to mind. There are recordings of him reciting his work, but I always felt that he wasn’t especially interested in performance. So for Datum Point, silence felt right. If I had forced a voice onto it, it would have betrayed that initial experience of reading—of not hearing.”

Throughout Orikasa’s work, there is a shift in technique, but he says it is not something he does consciously. “It’s more that each original text I work with demands a different technique. In trying to respond honestly to the text, I end up developing new methods. The style shifts because the literary source is different.”

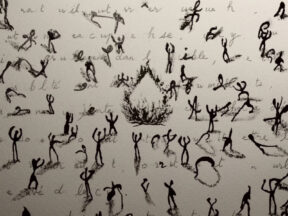

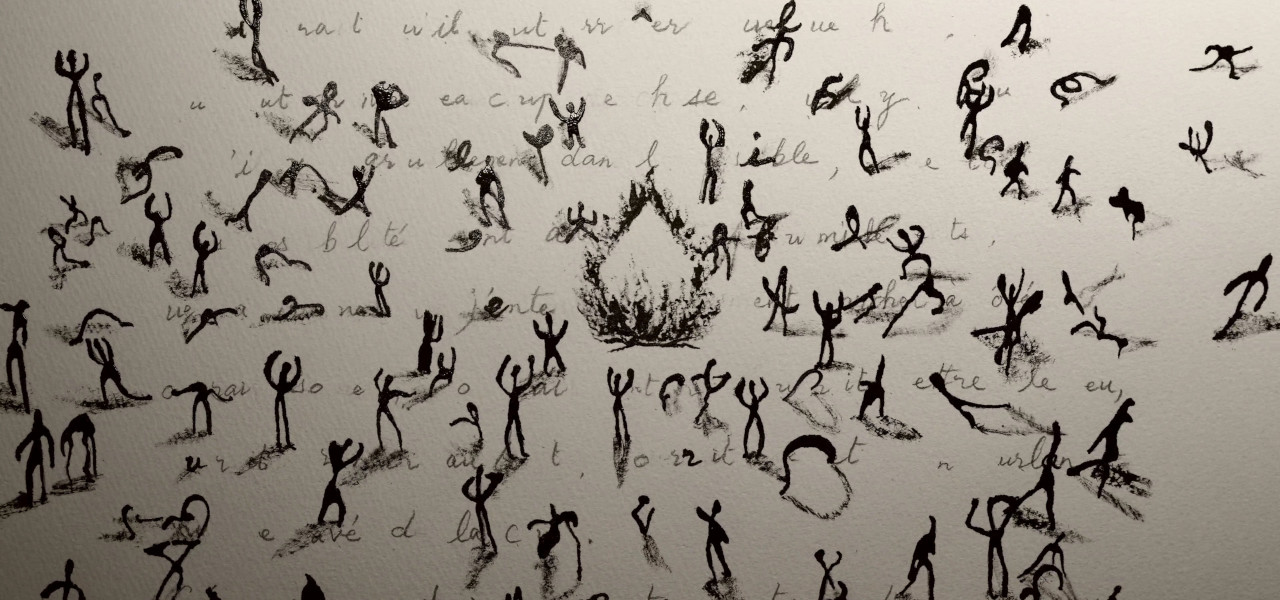

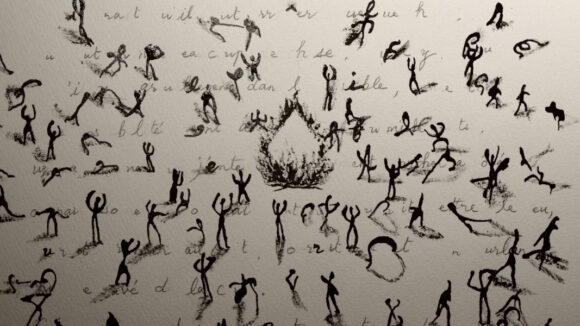

In Miserable Miracle (2023), Orikasa draws from Henri Michaux’s book of poetry and drawings about his experiences with mescaline. “I read Henri Michaux’s work in Japanese translation around 2012,” he says. “Of course it’s made of nothing but letters on a page, but when I read it I had an overwhelming flood of images.”

The structure of Michaux’s book struck him. “On the page there are essentially two rows of text: a main text and, running alongside it, something like notes, summaries, or parallel thoughts. They overlap and contradict each other. Michaux said this form reflected his experience of writing under the influence of mescaline, when several streams of thought run at once.”

Words appear and start to vibrate and darken. Letters take on human forms and walk across the page. Hasty sketches of mountains form, collapse, and merge. Then whiteness, followed by a sea of words floating about. Suddenly there is a shift to colour as the narrator’s voice occasionally breaks in two – basically a guy on a drug trip, it seems. At times the voice feels like too much, pulling us away from private moments with the imagery, but maybe that’s the point: written words, voices, drawings, colours all colliding. A cleaning woman interrupts with a knock. He wants to punch her. The letters make violent gestures. A beautiful collage of bubbling, torn colour shapes appears, then everything breaks apart and turns to black. The writing, the drug trip – it’s finished. The miracle of the miserable has concluded.

Finding the balance between sound and image is always tricky. “Very difficult,” Orikasa admits. “My usual process is to record the voice first and then build the animation around it. Later I sometimes listen only to the voice and think, ‘Maybe this alone is enough. Maybe the audience can imagine the images without me drawing them.’ I’m still exploring that relationship—the distance, or lack of distance, between sound and image. Ideally, my films could stand on the voice alone, but often I find myself drawn to adding other sounds or music as I work.”

With The Graffiti (2025), Orikasa returns to Japanese literature. Rakugaki (The Graffiti) is the second installment in the Bungaku Bideo series, which fuses Japanese literature with animation. For this short, he selects a prose poem by Makoto Takayanagi, narrated by the poet himself.

The poem evokes a restless night wandering urban streets until the tired dawn reveals a blot of black graffiti. The speaker describes repeated, futile attempts to erase the mark—only for it to reappear. Orikasa’s delicate pencil and ink-on-paper drawings capture the blurred fragility of Takayanagi’s words. The film unfolds into a dance between written and spoken language and image, celebrating graffiti-stained urban spaces and the new meanings they impart, like theatrical stage sets. The speaker could be a city cleaner doomed to scrub away the graffiti or a passerby in the throes of insomnia.

“Words are merely written on the surfaces of things,” says Orikasa, “but I had the intuition that when the words change to something completely different, this world would also radically change.”

Looking across his films, it might seem like Orikasa is constantly changing styles, but for him it’s simply a matter of following the text. “It doesn’t come from a strategic desire to ‘change style,’” he says. “It comes from following the demands of each text. With Graffiti, for example, I felt the writer used words like objects. I wanted to use something very tangible that I could feel with my hands. In the end, most of the objects in Graffiti are not clay but Styrofoam. The amount of legible lettering in my recent films has actually been decreasing. There are more patterns and more purely visual elements now. In a way, all of my works up to this point may have been a long preparation for saying goodbye to words—moving beyond literal text.”

His process is a mixture of planning and improvisation. “There are always things I can decide in advance and things I can’t,” he explains. “If I know which text I’m working with, I can estimate how many frames I’ll need and how long the film will be. But how those frames are filled—what happens in each shot—is often improvised.” Datum Point was the most shocking example of this. “I spent about a year shooting it. For the first two months I did some previews, but for the next ten months I didn’t preview anything. I didn’t use Dragonframe or do line tests. I just kept shooting, like working with film stock, and only at the end did I finally see what I’d done. The same is true, to a degree, for Miserable Miracle. I try not to go back and ‘fix’ things. I think of the act of making the film as one continuous event, and the finished film is simply a recording of that event.”

Most recently, Orikasa has started collaborating with Boris Labbé on a project. “This is my first co-directed work,” he says. “Boris was making his first VR piece, Ito Meikyū, based loosely on a tale from The Tale of Genji and The Pillow Book, and he needed Japanese calligraphy—Japanese text as a visual element. That’s how he invited me.”

Through all these shifts, Orikasa keeps returning to writing: words that move, blur, vanish, and sublimely stain the silence they emerge from.

Pictured at top: Miserable Miracle

.png)