‘Animation Is Something You Could Spend Forever On’: Kenji Iwaisawa On ‘100 Meters’ And Re-Touching ‘On-Gaku’

In the whirlwind of Annecy, where every screening is an open window into the bright and infinite world of animation, going from one theater to another can feel like running an endless sprint. It’s no surprise that 100 Meters resonated with the festival’s crowds, eager to discover the latest film by acclaimed On-Gaku: Our Sound director Kenji Iwaisawa.

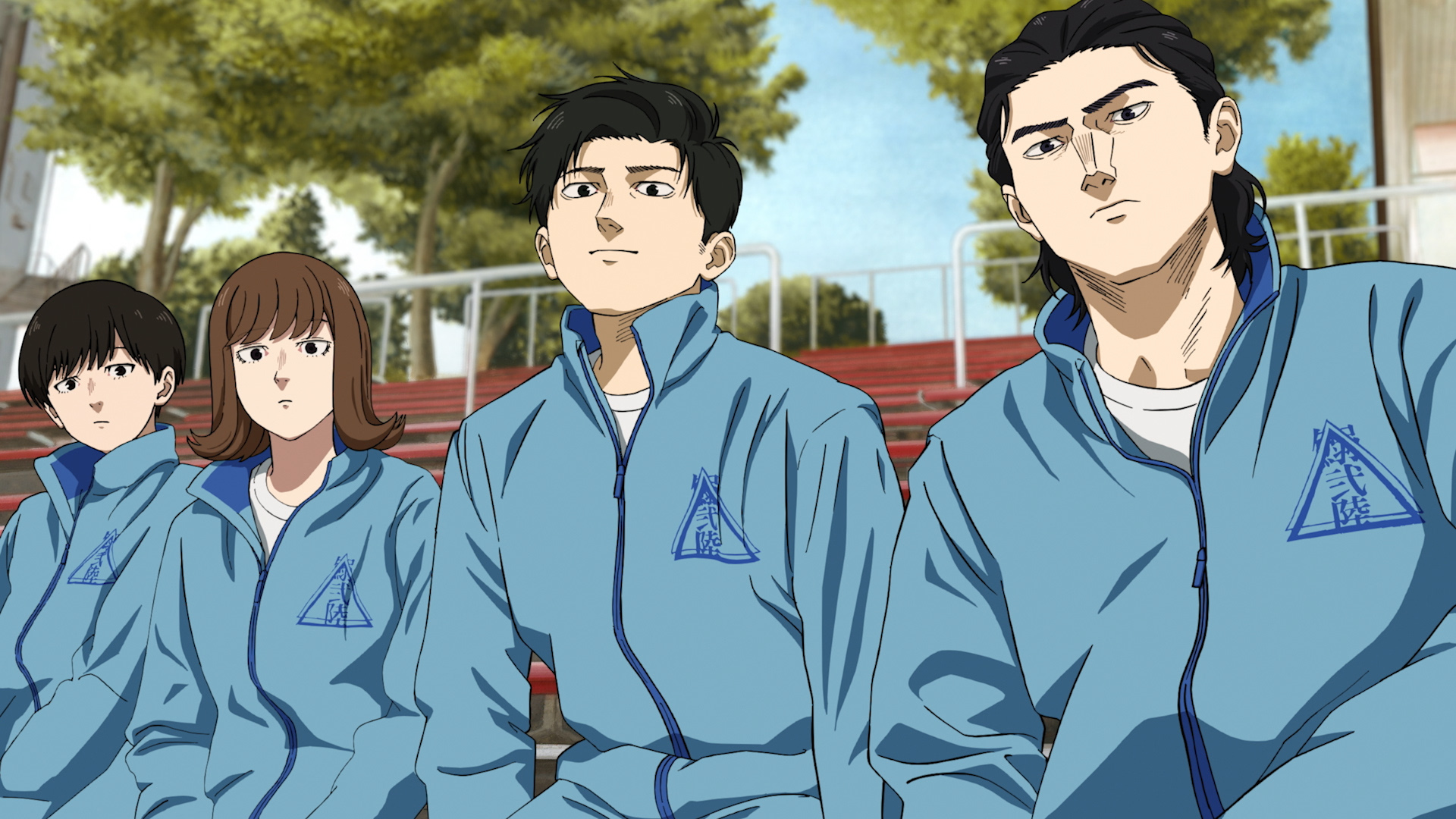

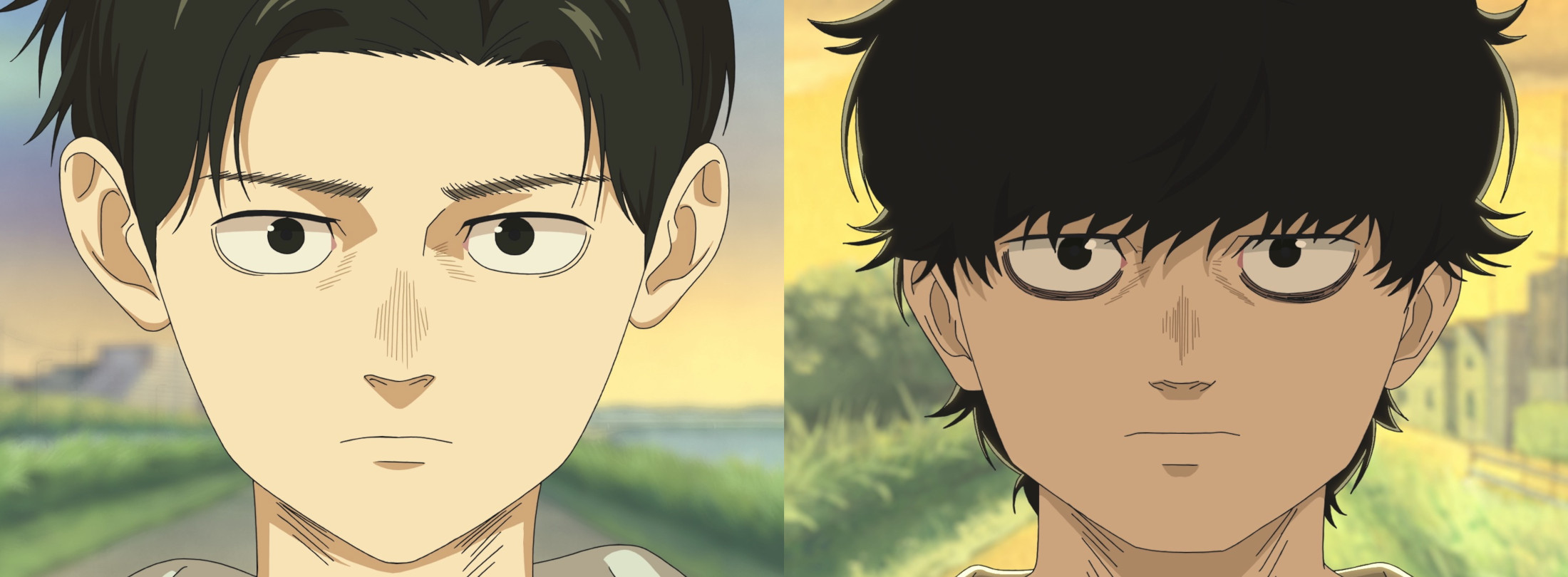

In his new feature 100 Meters, director Kenji Iwaisawa (On-Gaku: Our Sound) leaves the slacker comedy genre for a more grounded story drenched in sweaty sports rivalry and rooted deep in red-dust tracks. Born to run, sixth-grader Togashi wins every race without effort — until he meets Komiya, a transfer student full of determination but lacking technique. As the champion begins to tutor the challenger, the rivalry builds. In the relentless pursuit of victory, Togashi and Komiya meet again, revealing their true selves on the track.

As GKIDS sends 100 Meters to select U.S. theaters on October 10 before a nationwide release on October 12–14, we sat down with the director to dive deeper into his production process and to inquire about the recently re-drawn edition of On-Gaku that accompanied 100 Meters’s Japanese release in September.

In addition to the interview, Cartoon Brew was given exclusive access to two new stills from the film, seen below.

Cartoon Brew: Iwaisawa-san, can you elaborate on what drove you to this story in the first place?

Kenji Iwaisawa: What I was interested in focusing on was the story of this protagonist, Togashi. As a child, he is very good at sports, and when he loses, he drops out and becomes depressed.

In real life, more often than not, if we lose to someone, we drop out and we don’t come back. With Togashi’s tale, I could tell the story of a person who lost everything, who goes to the lowest of the low, and then has a comeback through real effort.

I think we can all relate to this story of having someone in your school who is just naturally good at something. But I think there’s a limit to that. And so, crafting this comeback story was really appealing to me.

In 100 Meters, sport can also be seen as a way to free oneself, to overcome challenges. Was that something that resonated with you?

There are two answers to your question. In terms of sport, I was an athlete as well. I played baseball in high school, so I know a thing or two about sportsmanship and overcoming things through sports. It does give you a certain freedom, which I find very interesting on many levels.

For the second part: I don’t know if you’re aware of it, but on late-night Japanese TV, they’ll often air boxing matches. Those athletes are not well known, but I remember one particular fight that I watched. A veteran boxer was facing a newcomer. I didn’t know their names, but I could tell from the way they were fighting who was the veteran and who was the “young punk.” When the match started, the young came up to the veteran and started throwing punches. The other one held up his gloves, and after a few minutes of getting pummeled, he threw just one punch — a precise blow that struck the young one and staggered him. The veteran knew it was his moment, and he went for the K.O.

The reason I tell this story is because that moment is what sport is all about: having that wisdom to feel the right timing. A 100-meter race is an extremely simple sport, and the conditions are all the same. Of course, you can have physical differences — veterans might have less power but more wisdom than younger athletes. Everybody is coming to the same sport and the same rules but from different angles, and I wanted to distill that feeling in 100 Meters as well as the philosophy behind it.

As both boxing and the 100-meter race are all about finding the right moment, they’re also highly visual sports with striking bursts. How did that shape your approach to the film?

To be honest, I didn’t really think about it like that before — how momentum plays into the visual and how it might affect my visual designs. But in terms of my process, I think it’s interesting because I have a lot of momentum myself. Even if a piece is almost at completion, if I think of something, I want to do it immediately.

To go beyond that, I think sound design also plays a key role in these moments within the film, as they actually represent those sparks. At the start of each race, you get this really loud noise that marks the beginning of this particular fight, which gets your blood flowing and gets things into motion.

Can we talk a little about the technique? What challenges did your choice of multiple techniques for this film present?

I wouldn’t say that these were new challenges, as I did not experiment with techniques I hadn’t practiced before on other projects. It was only when we strung all the pieces together that I realized I had indeed used a lot of different techniques on this project, but it wasn’t a real conscious choice.

The one scene that really brought a new challenge to me was the rain scene, which is near the very end of the film. It was done with rotoscoping but from one single cut, where the camera pans and the racers are getting ready under the downpour. That was something I hadn’t tried before.

Going back to sound — how did you approach this key aspect of the project?

From the beginning, I had a very clear idea of what the sound would look like in this film, how it would turn into a clear image. In discussing it with my producer, it was important to me that sound effects and music would not be separate, and that they would go hand in hand to create the soundtrack of this film.

In Japanese filmmaking, there is usually a sound-effects producer and a soundtrack producer, with very distinct processes. In this case, I wanted to bring those two together, and I actually directed the sound of the film as well. We were in the studio together most of the time, giving input and feedback to each other. Seeing them work together and collaborating with them was a very special experience.

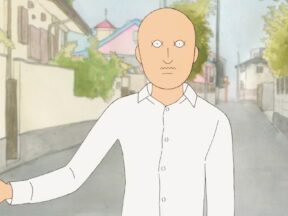

Along with the release of 100 Meters, you also went back to On-Gaku for a “brush-up” re-release. How did it feel to return to a project you had worked on for so long — and to these characters?

Completing 100 Meters, I think — even if I’m not sure I’m seeing it objectively — I reaffirmed my own artistic identity, or at least the kind of work I want to create. It’s a unique way of making things, but with this production, I finally felt like I understood my own individuality. Seeing these two films side by side, I finally grasped my own style. On-Gaku was released immediately after completion, and then the COVID-19 pandemic hit within a few months. That freed up time, so I had been polishing up the parts I hadn’t finished.

Redoing parts of your film could have turned into a whole remake. How did you know when to stop?

The key points are not adding new cuts, not altering the runtime, and absolutely not changing the content. It’s simply about refining the visuals. Since it’s a type of refinement that probably only the creators would notice, I don’t think the impression changes drastically before and after the refinement. Animation is something you could spend forever on if you don’t have specific deadlines. So being able to do this feels like I got a little extra time.

What do you hope for this re-release?

If it were possible, I’d love to secretly replace all the un-brushed-up versions currently out in the world with the brushed-up version. But right now, I’m making a short film about 10 minutes long at my studio. I’m involved as a producer, and the director is one of our studio’s young staff members. I want them to gain the experience of creating something as a young team. I hope there will be an opportunity to show it somewhere.

.png)