2026 Oscars Short Film Contenders: ‘The Quinta’s Ghost’ Director James A. Castillo

Welcome to Cartoon Brew’s series of spotlights focusing on the animated shorts that have qualified for the 2026 Oscars. The films in this series have qualified through one of multiple routes: by winning an Oscar-qualifying award at a film festival, by exhibiting theatrically, or by winning a Student Academy Award.

Today’s short is The Quinta’s Ghost from Spanish filmmaker James A. Castillo, produced by Ilusorium Films and Martirio Films. The film world premiered at Tribeca in June, and later won awards at Sitges, Thessaloniki, and Alcine, the latter of which was an Oscar-qualifying prize.

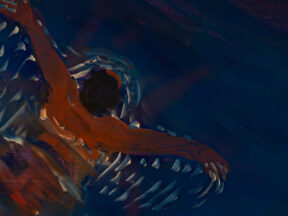

The Quinta’s Ghost follows an aging, ailing Francisco de Goya as he isolates himself in La Quinta del Sordo, where illness, memory, and fear coalesce into spectral manifestations that push him toward the creation of his Black Paintings; the film’s VR-assisted visuals render this unraveling in a swirling, painterly aesthetic featuring thick, angry brushstrokes that mirror the protagonist’s own work. Shadows smear like wet pigment, figures distort as if scraped from the canvas, and the house itself warps into a dim, breathing vessel of dread, producing a single claustrophobic fever dream in which art becomes both confession and exorcism, all narrated by the building itself, voiced by the iconic Spanish actress Maribel Verdú.

Cartoon Brew: What was it about this story or concept that connected with you and compelled you to direct the film?

James A. Castillo: The original impetus for the film came from wanting to craft a horror film in animation that would allow me to have a conversation around the concept of grief, but I was struggling to find the right vehicle to do so. During the pandemic, an already existing obsession with Goya started growing, and I devoured a bunch of books on his life and work, and, at one point, all the pieces came together to form an idea. A man struggling with his own mortality deals with his demons the one way he can, by painting! It felt universal, it felt rich with potential, and, more importantly, it allowed me to imbue the horror elements with pathos and humanity.

What did you learn through the experience of making this film, either production-wise, filmmaking-wise, creatively, or about the subject matter?

I think a lot of the growth was more personal than practical. Of course, we all learned new skills, software, and became Goya experts for a little while, but the biggest lessons came from our own internal struggle. We learned to be more defiant with the film, we learned to trust our instincts, and were rewarded by taking risks in the process. I think, if anything, making this film has emboldened us to pursue a path towards pushing animation towards uncharted lands where the medium evolves both in its techniques and in the themes and topics that it is able to address.

Can you describe how you developed your visual approach to the film? Why did you settle on this style/technique?

There were two paths to creating the look of the picture. The first was, obviously,the pictorial; we studied Goya’s art thoroughly and broke down his compositions, color palettes, shapes, brush strokes, etc. That informed a lot of our design language, both in characters and setting. The second path of influence was filmic; we were inspired by films from the 1970s, such as Barry Lyndon (Kubrick) and Nosferatu (Herzog), to create subtle performances and a strong sense of dramatic lighting and camera work. This allowed us to ground a lot of the more fantastical elements into something that felt recognizable, but new and intriguing at the same time.

How did you decide on which parts of Goya’s later life would be literal in the film, and which would be fictionalized?

It all came down to the thematic purpose of the film. We told ourselves from the beginning that we were not making a biopic or a documentary; we were building fiction around a real thing that happened, and we took liberties accordingly. We needed to make sure that the viewers would empathise with Goya, so we kept those historical facts that furthered that intention, and we omitted anything that would distract from the main objective. To be fair, it was not much; we stayed pretty faithful to the historical facts.

.png)