Book Review: “The Noble Approach: Maurice Noble and the Zen of Animation Design”

The Noble Approach: Maurice Noble and

The Zen of Animation Design

By Tod Polson, based on the notes of Maurice Noble

(Chronicle Books, 176 pages, $40, pre-order for $26.50 on Amazon)

By the modest standards of celebrity in the animation world, Maurice Noble is a rockstar. Few Golden Age layout artists or production designers, with the exception of Eyvind Earle, Mary Blair, and possibly Jules Engel, command Noble’s name recognition. Maurice’s fame is primarily attributable to his long-term association with Warner Bros. director Chuck Jones.

Noble’s collaborations with Jones include such classics as Robin Hood Daffy, Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century, What’s Opera, Doc?, How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, The Dot and the Line and many installments of the Wile E. Coyote/Roadrunner series. Thanks to this beloved resume, Noble has been spared the ignoble anonymity of so many other classic animation artists.

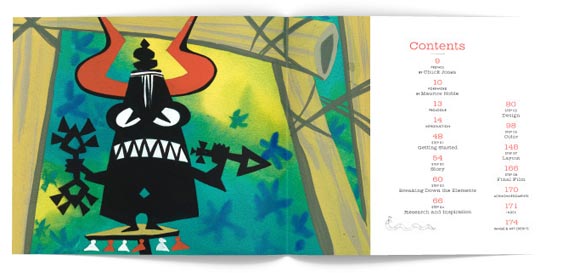

With such standing in the animation world, and even an entire book-length biography already devoted to his life, one could reasonably expect that everything that could be said about Noble has already been said. Tod Polson’s The Noble Approach proves that that’s not the case. Polson has put together an irresistible package that fuses biography and art instruction, each of its pages filled with invaluable insights and incredible artwork, much of it never-before-published.

Polson is one of the Noble Boys, the informal name given to a group of men (and women) whom Noble trained throughout the 1990s at studios like Chuck Jones Film Productions, Turner Feature Animation and his own company, Noble Tales. The Noble Boys have gone on to big things in the animation industry: Ricky Nierva was the production designer of Pixar’s Up and Monsters University; Don Hall directed Disney’s Winnie the Pooh and is writing and directing the upcoming Big Hero 6; Jorge Gutierrez co-created the Nick series El Tigre: The Adventures of Manny Rivera and is directing Reel FX’s 2014 feature Book of Life.

Before Noble’s death in 2001, some of the Noble Boys had encouraged Maurice to write down his thoughts about design and layout for an eventual book. Polson has adeptly compiled and edited those notes into this book, combining them with the remembrances of the other Noble Boys about their interactions with Maurice and lessons learned from him, as well as archival interviews with Noble and original commentary from artists like Susan Goldberg and Michael Giaimo.

Polson devotes thirty-four pages of the book to a biography of Noble, following his career path that began professionally at Disney on films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Bambi. In spite of its brevity, this biographical section manages to be more revealing and historically well-rounded than the disappointing 2008 book Stepping into the Picture: Cartoon Designer Maurice Noble by Robert J. McKinnon. That well-intentioned book missed the mark—badly. It was understandable that McKinnon’s layperson knowledge of the animation process prevented him from providing the kind of process detail that is in Polson’s new book, but his sins of omission made it a letdown as personal biography, too.

Basic and vital details about Noble’s personal and professional relationships that were omitted in that earlier biography are thankfully included in Polson’s book. For example, we learn that Mary Blair and Maurice Noble were not only classmates at Chouinard Art Institute, but also a romantic couple. That’s a revealing historical tidbit considering that Noble’s giddy use of color was second only to Mary Blair during the Golden Age. Polson clearly expresses Noble’s unflattering thoughts about Sleeping Beauty production designer Eyvind Earle, with whom he worked during the production of the industrial film Rhapsody of Steel, whereas the earlier biography only vaguely acknowledged that Noble “may have had some difficulty working with Earle.” Polson also discusses Noble’s more-important-than-acknowledged role on Chuck Jones’ Oscar-winning short The Dot and the Line, an issue that was left untouched in McKinnon’s text.

For all its historical value, the real meat of the Noble Approach follows the biography. In the subsequent sections, we learn about Noble’s artistic process step-by-step from the beginning of a film through its completion. Chapters are devoted to starting a film, story, breaking down the elements, research, design, color, layout, and finally, an oddly ineffectual and anticlimactic two-page chapter devoted to the finished film.

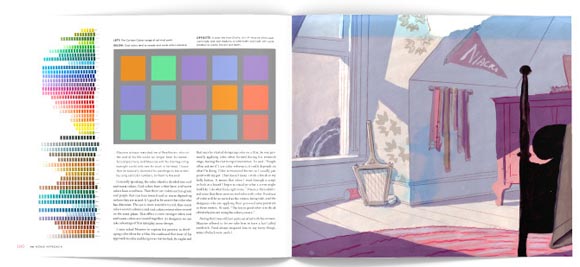

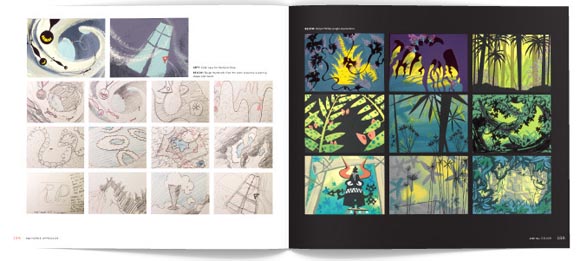

The material covered in these chapters will undoubtedly be familiar to anyone with an art background—values, contrast, simplifying elements, visual hierarchy, compositional grids—but the provided examples of Maurice’s own work gives the reader a fresh entry point into each of these well-worn topics. The section on color is particularly fantastic. Color is one of the hardest elements to get right in animated film, and Maurice knew how to walk the thin line between playful and tacky. Polson does a superb job of explaining how Maurice managed to do this by doing a deep analysis of his color palettes.

The section on color, for all its strengths, also represents one of the parts of the book that I wish the author had expanded his scope. Polson makes clear from the outset that this is “Maurice’s book,” but I can’t help but think our appreciation for Noble would have been enhanced further by offering some discussion of his contemporaries at Warner Bros., like layout artist Hawley Pratt and background painter Paul Julian. Contrasting the color theories of Julian, who was the studio’s true master of color in my opinion, would have been an enlightening sidetrip.

A lot of the book’s best information isn’t technical, but rather practical advice that is the wisdom of experience. This is true of Noble’s thoughts on selling an idea:

To be a successful designer, being able to sell a good idea is just as important as coming up with the idea itself. It’s hard to sell something simply because you think it feels right. You have to be able to logically discuss why it feels right.

—and his thoughts on why the production methods of yesteryear resulted in better cartoons:

There is more talent working in the industry now than ever before, but sadly the vast majority won’t have the opportunity to work on really good creative stories. The problem isn’t always the type of stories being told; it’s more in the way these stories are being told and developed. There is no room for visual exploration. There is no time for thought and craftsmanship. There isn’t the chance for crews to build trust and synergy.

The production design tips that he offers are applicable to artists today, even if the tools of the trade have changed:

I suggest putting all your research materials away once you start designing and never refer to them again. This may prove difficult at first. But I’ve found that if you are tied too closely to your reference, your designs will tend to look stiff. You will miss out on many fun design opportunities.

or…

Starting rough and not getting specific too early will allow you to keep your design ideas flexible…The more ideas and work you have, the more design possibilities you will have to choose from.

The Noble Approach: Maurice Noble and the Zen of Animation Design ranks among the most unique and delightful animation books in recent memory. It goes without saying that the book’s well-balanced mix of technical tips and anecdotal advice makes it a must-buy title for professional artists and students, but it should also appeal to fans of classic of animation who will surely gain a renewed appreciation for the Chuck Jones canon. The book will be released on October 1st. For those who are still in need of convincing, the book’s official blog gives a nice sense of the book’s content.

.png)