Inside The Making Of ‘The Quinta’s Ghost’: Gothic Horror, 3D Brushstrokes, And 35mm Film

Spanish Oscar-shortlisted short The Quinta’s Ghost immerses audiences in Francisco de Goya’s final, haunted years. Its making-of, now available online, reveals something equally compelling and also a bit mad: a rigorously crafted, deeply researched production shaped by years of artistic and technical problem-solving and exploring techniques that had never been used in this way before.

In the behind-the-scenes documentary, director James A. Castillo and his team break down how a short inspired by Goya’s Black Paintings and the country house that hosted them became an ambitious fusion of art history, animation, and cinematic experimentation.

Castillo describes the project as an attempt to approach Goya through gothic horror, exploring “death, the relationship between the artist and the work… from the point of view of mortality.” Plotting out the story was “complex,” he explains, not only because Goya is a historical figure who must be treated “with enormous respect,” but because the narrative carried significant ambition.

“The Quinta del Sordo itself is a character,” Castillo says, which demanded a presence as strong as that of Goya himself. That idea unlocked the film’s narrative device, the house as narrator. Too really nail down the film’s gravity, iconic Spanish actor Maribel Verdú (Y tu mamá también, Pan’s Labyrinth) was recruited to voice the home, the only speaking part in the short.

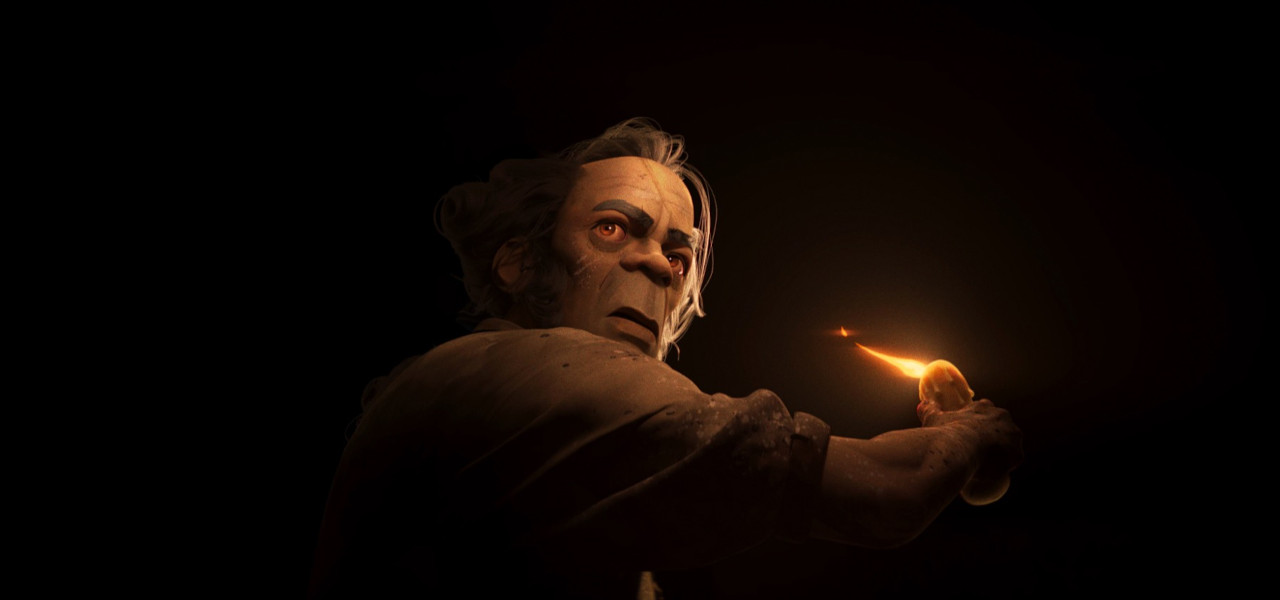

Visually, the challenge fell heavily on art director Pakoto Martínez, who spent four years generating artwork inspired by Goya’s grotesque figures. “Interpreting Goya’s characters is extremely complex,” he admits. At one point, he realized he “wasn’t understanding Goya,” and made the radical decision to start over. “I decided to begin from scratch… working directly with loose brushstrokes and raw forms.” The result was a deeper, more intuitive homage to Goya’s Black Paintings.

Castillo was adamant that animation was the only viable medium. Goya’s work is “so plastic,” he says, that animation allowed them to compress “all that magical essence” into an audiovisual form without breaking the pact of fiction.

The production, led by Illusorium Studios, pushed technical boundaries. Stylized, painterly designs had to be translated into three-dimensional space. Lighting was designed to be “very dramatic,” with a photorealistic treatment that contrasted with the expressive characters. “Everything is planned, programmed, studied down to the millimeter,” Castillo notes of the meticulous 198-shot production.

In a particularly bold move, the team printed the fully digital short onto 35mm film and rescanned it, embracing dust, flicker, and imperfection. The goal was immersion; to make audiences forget they were watching animation.

By the end, even the creators were overwhelmed. When Pakoto finally saw the finished film, he described it as “almost a trance.” What had once been “just ink on paper” became “pure Goya.”

.png)