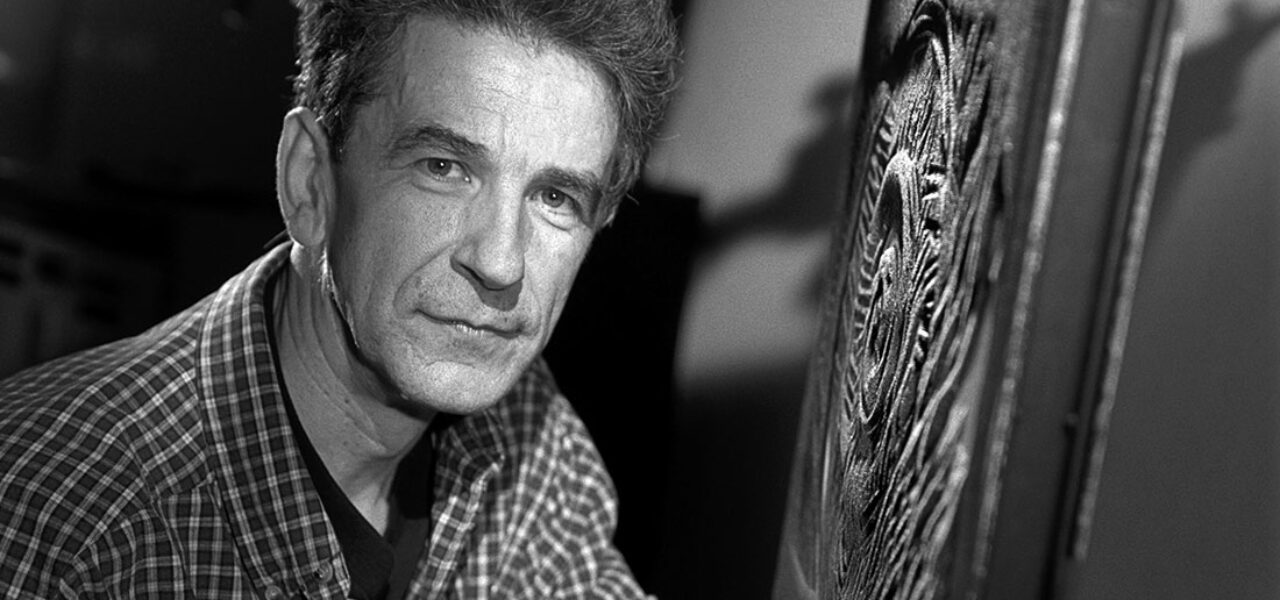

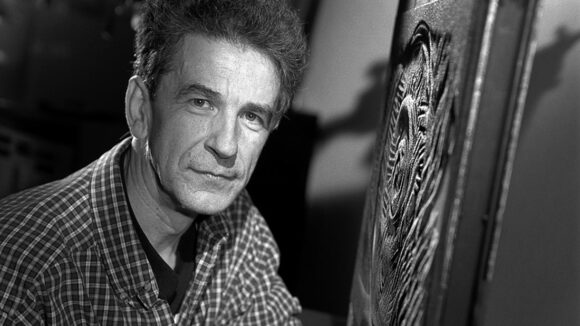

Jacques Drouin, Master Of Pinscreen Animation, Dies At 78

The sudden passing of animator Jacques Drouin from a stroke was a shock to many in animation, especially in the halls of the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), where he was an influential and beloved fixture for decades.

“I thought he was eternal,” says former NFB colleague Hélène Tanguay.

“He always seemed to me to be forever young,” says NFB filmmaker Don McWilliams. “Jacques was a true gentleman with an iron will, as he explored the human condition and advanced the art of the animated film.”

Drouin will be remembered throughout the animation community for his mastery of the pinscreen, the device invented by Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker. Drouin’s use of the rare tool left us with a unique body of work, including the widely acclaimed Mindscape (1976), Nightangel (co-directed with Břetislav Pojar, 1986), and his final film Imprints (2004).

Drouin was born in Mont-Joli, Quebec in 1943. His journey towards the NFB began when he was a teenager. “My parents moved to Montreal in 1955 and that was about the time the NFB building was in construction,” he recalled in January 2021. “We lived in an area where employees of the Film Board were coming from Ottawa to look for new houses to buy. So I heard about the Film Board quite early.”

A few years later, while in his final year at L’École des Beaux-arts de Montréal, Drouin finally entered the freshly painted walls of the new NFB headquarters in the city. “[Animator] Kaj Pindal was giving occasional talks, and because of this we went to the NFB one day to get our paper perforated,” he said. “That was the first time I entered the Film Board.”

Drouin’s interest in animation grew even more during Expo 67, which was held in Montreal. He visited an animation exhibition where he first glimpsed a small prototype of Alexeieff and Parker’s pinscreen. “I remember going to see many screenings of animation during the World’s Fair. It was fantastic.”

In 1968, Drouin headed west to UCLA to study filmmaking. “I only took one animation class there. It was very basic. I wasn’t that interested. I learned to make dope sheets and prepare artwork but my animation knowledge was very limited.” Drouin made a few films at UCLA (including animated short The Letter) before graduating.

Back in Montreal, Drouin began work as an editor for tv sports programs. He did this for a couple of years before getting up the nerve to go to the NFB with some animated films he had made. “I had done some pixilation and cutouts and I didn’t see much of a future with my job. I was not too happy about the work, so I went to see René Jodoin [head of the NFB’s French animation unit].” About a year later Drouin received a call from Jodoin’s secretary encouraging him to apply for a three-month internship in the animation department. He went for the interview and was chosen.

During the internship, Drouin stumbled upon a device that would change his life. “I was told that the pinscreen of Alexeieff was there. I got a 16 mm Bolex camera and [filmmaker Norman McLaren] told me I could take a few days to test the pinscreen.” Drouin had done some engraving work in school and saw possibilities with the pinscreen. “I thought I was the ideal person to try it. I felt there was a connection since this was the invention of an engraver [Alexeieff]. I was there a very good moment. It’s changed my life.”

For the rest of his internship, Drouin experimented with the pinscreen, eventually completing Three Exercises on Alexeieff’s Pinscreen (1974). After the internship, Drouin went back to editing. It would be a couple more years before he returned to the NFB to pitch Mindscape, a pinscreen film about a painter who enters his own painting.

Drouin knew he wanted a film without words that fused the real and the imagined. As he explained:

I really liked Saul Steinberg drawings. One of them is of an artist with a fingerprint for a head. It struck me that it was about impressions left behind in a painting. I was also interested in Carl Jung at the time. I just put it all on paper and made a few images that became more or less a storyboard. I then figured I had a nine-minute film and it would take me nine months to make it. It ended up taking twice as long. I really had no idea how much time would be needed between each image. I went with intuition and little precision. There was a lot of improvisation that happened.

Mindscape made its debut at the inaugural Ottawa International Animation Festival in 1976, where it took home a jury prize. More importantly, this was also where Drouin met Alexeieff: “McLaren insisted that Alexeieff come to see Mindscape in person. We spoke a few words during lunch. That evening the film was shown and as a gesture of continuation, a 35 mm print was given to him after the screening. Then I visited him in Paris the following year and we had some conversations. I probably saw him three or four times before he died.”

Despite the praise for Mindscape, Drouin found himself going back to editing work again. “I struggled during those years doing many things,” he said. In 1981 he would finally be hired as a full-time director at the NFB, a position he maintained until it was abolished in 2004.

After Mindscape, Drouin made Nightangel, a story about a blind man and his guardian angel that combines puppet and pinscreen animation (with color, for the first time in his filmography). This challenging co-production — Czechoslovakia, the partner country, was in the midst of many sociopolitical changes — was co-directed by Czech animator Břetislav Pojar.

Outside of contributions to a handful of animation projects, Drouin would not make another film until Ex-Child (1994). Made for the well-intended but poorly conceived Rights from the Heart anthology series (which was inspired by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child), the film tells a story of a father and son who are enlisted to fight in an unnamed war. While there are some striking moments, for the most part, Ex-Child feels a bit stiff and naïve.

Drouin acknowledged problems with the film but said that it was a learning experience: “With the limitation of the story, it pushed me to do something other than metamorphosis. I had not really done very realistic actions with the other films, but with this I had to make some people walk. It was a challenge for me to do something that was not too friendly with the pinscreen.”

His next film, A Hunting Lesson (2001), was based on a famous children’s book by Jacques Godbout about a boy who is fascinated by his neighbor, a hunter. Drouin recalled: “That film is probably the most illustrative I could get with the pinscreen. It was another kind of challenge because I was shooting in color and had to make some ambience with it. The pinscreen was also too small for the images I wanted to do, so I had to make separate sets that I would photograph and make believe it was a continuation of the pinscreen itself. It was fun to try, but I spent too much time trying to solve puzzles.”

Imprints, the director’s final short, marked a shift back towards a less linear, more abstract approach. “It was a very physical film. I was sweating all day because I was working under difficult light conditions and making the screen move. I had a device to make it turn. It was like making a first film again. I was over sixty and I guess I finally lost my caution.”

Before heading for the NFB exit doors, Drouin made sure to share his knowledge of the pinscreen. Marcel Jean, artistic director of Annecy Festival, remembers: “He gave a masterclass and animator Michèle Lemieux had the opportunity to touch the thorny beast.” Lemieux went on to complete her first pinscreen film, Here and the Great Elsewhere (2012).

“Jacques gave me so much,” she says. “To start with, the privilege of being his successor to the pinscreen. He gave me room to be myself, along with the confidence to tackle this somewhat terrifying tool. Those hours we spent side by side as he taught me how to repair and maintain the pinscreen are something I will cherish forever. He was passing on the role of protector of an imposing but fragile instrument, one haunted by its inventors’ painful past, and I understood that I had become its keeper and curator. These moments are among the most precious, the most moving, of my entire life.”

“A few years later,” adds Jean, “Lemieux then gave a masterclass to train young French filmmakers on the pinscreen. Today, the pinscreen is alive and well and this is largely indebted to Jacques Drouin.”

We can learn much about animation and its expressive reach by revisiting Drouin’s career. But at the end of the day, what matters most is the quality of the person behind the works. Drouin was a stellar human being known for his compassion, humor, humanity, and modesty. The disbelief and deep grief that many are feeling over his loss speaks volumes about his character.

“Throughout his career,” notes Julie Roy, the NFB’s director general of creation and innovation, “Jacques carried the legacy of this imposing apparatus of film heritage. But he also stood out for his exemplary involvement in the day-to-day activities of the NFB and with the broader animation family on the world film scene. He was endlessly erudite, a patient and attentive teacher, and a warm and caring colleague. But above all, a man of exceptional humanity.”

“The single greatest kindness ever offered to me by a work colleague,” says Halifax animator Heather Harkins, “was the moment when Jacques Drouin pulled me aside in the corridors of the NFB in 2003 to ask, ‘Are you okay? This place is not a normal place.’ Full disclosure: I was not okay. He was warm, friendly, and always willing to make room for one more person at his cafeteria table.

“Day after day, Jacques showed up to work at an institution whose highest executives seemed indifferent to its artists, and he persisted in sharing his bright beautiful creativity with the world.”

.png)