A Character Animator’s Adventures In Motion Design

Morgan Williams has been a professional animator for almost 30 years and an animation educator for almost a decade. He has deep experience creating 2d character animation for commercial applications and children’s television, and was the lead character animator on the end title sequence of Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. As an educator, he teaches animation fundamentals and character animation in the Department of Motion Design at Ringling College of Art and Design, and online at School of Motion through his courses Character Animation Bootcamp and Rigging Academy.

Below, Williams shares some observations as a “traditional” character animator now working mostly in the world of motion design education. Over to him:

Where Character Animation and Motion Design Meet

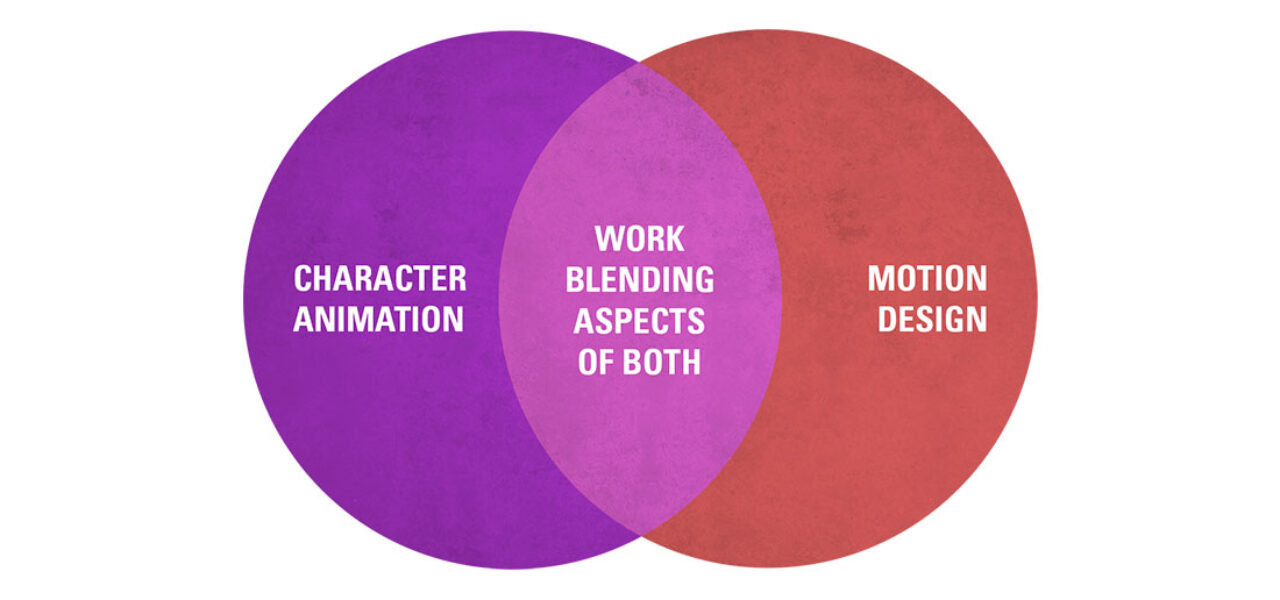

“Motion design,” which we could define as a discipline that pairs graphic design with animation and vfx, and “character animation,” which we might define as a discipline that focuses on the animation of figurative, illustrated characters, could be seen as two parts of a Venn diagram. There’s a lot of room for overlap in the middle.

While a big chunk of the motion design industry is concerned with animating graphics, logos, and typography, there are many motion design studios — like Buck, Giant Ant, and Animade (to name just a few) — that employ a lot of character animation in their work. One only has to look at Animade’s showreel to see the predominance of character animation in what is ostensibly a “motion design” studio.

Even more “traditional” motion design work, like a logo with a figurative element or the ubiquitous “explainer videos,” often incorporates simple character animation to help communicate an idea in an appealing way.

Similarities and Differences

While the fundamental techniques of giving life to characters are fairly universal, we can still make a distinction between traditional, narrative character animation and more figurative animation within motion design.

Generally, the goal of “straight” character animation is to tell a linear story with a narrative arc. Conversely, the aim of a lot of motion design work is to communicate an idea or convey information in an engaging way. In this case, characters may not be part of a linear narrative with an emotional arc, but may simply personify a concept or illustrate an activity.

But there are gray areas. Sometimes the best way to communicate a complex idea is with a traditional, linear narrative. So motion designers may choose that method as the best solution to a client’s needs — but this is fairly uncommon.

Another difference — although there’s a lot of gray area here too — is stylistic. Both “pure” character animation and character animation within motion design employ figurative illustration. However, character work within motion design tends to be rooted more in the traditions of graphic design and what we might call “editorial” illustration styles, whereas narrative character animation tends to be linked more to the tradition of cartooning and comic art.

Of course, there is a lot of crossover here. Many “cartoon” styles are highly graphic, and many “graphic” styles are highly cartoony. But the examples below — from Giant Ant’s beautiful Slack commercial and Adult Swim’s brilliant Rick and Morty series — illustrate these “extremes” fairly well.

Some of these admittedly subtle differences can be traced to the history that informs these two disciplines. Modern motion design can trace its lineage through graphic design and experimental film and animation. Traditional character animation’s history moves through cartoon and comic art, narrative filmmaking and theater.

Why Teach Character Animation to Motion Designers?

Motion design, almost by definition, is a multidisciplinary field. A good motion designer needs to be a nimble and flexible artist, who can work in a variety of styles and techniques to address the needs of their clients. I think there are two very compelling reasons why motion designers should study the art of character animation, and add it to their “toolkit” of skills:

- Learning to draw figures is one of the best ways to learn to draw well because it’s so challenging. Similarly, learning to animate figures is one of the best ways to learn animation, because it’s arguably the most difficult form of animation. For a motion designer, animation — “giving life” — might often mean “giving life” to a logo or typography, but if you can bring a character to life, you’re going to be that much better at bringing non-figurative elements to life as well.

- There are many motion designers who have not studied character animation and/or are intimidated by its difficulty and complexity. Thus being able to handle character animation — and handle it well — makes you that much more valuable and marketable. And as we have seen, there really is a lot of character animation in motion design, so motion designers without these skills are missing out on a significant amount of potential work opportunities.

It’s All About The Fundamentals!

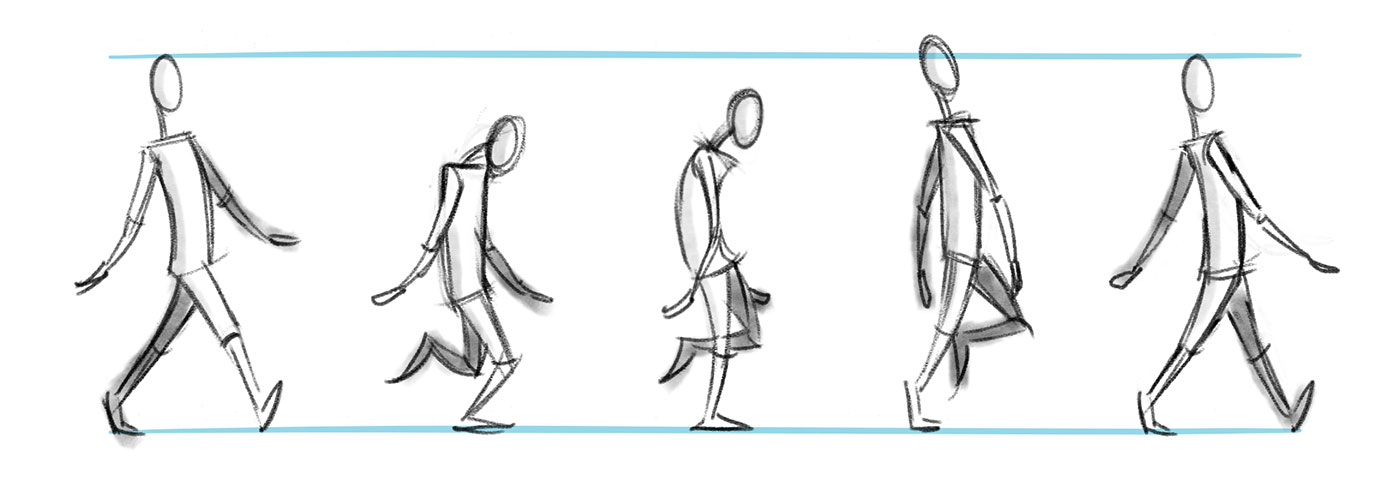

Even if they only create character animation once in a while, and however simple or “limited” that animation is, the motion design student who wishes to add character animation to their repertoire needs to learn the same fundamentals that all character animators study. In my experience working with students, even the simplest figurative movement requires a fairly deep understanding of character animation fundamentals.

“Limited” character animation, although designed to be simpler and less time consuming than “full” animation, is often very stiff and unconvincing in the hands of an artist who has not studied the basics of anatomy, performance, and the 12 principles of animation. Even if a motion designer is not expecting to work as a lead animator on a Disney or Pixar feature, they need the same base-level skills and understanding as the most advanced character animator.

This is really the area where the differences between more traditional, narrative character animation and character animation within a motion design context firmly end.

Software Considerations

My 2d character animation courses for motion designers, including Character Animation Bootcamp and Rigging Academy are mostly taught using Adobe After Effects with rigged puppets created with the third-party script Duik Bassel, which provides 2d rigging and animation tools similar to 3d animation software. I get asked about — and sometimes criticized for — this choice quite often.

What I often hear is something along the lines of: “Why aren’t you using Toon Boom or Moho? After Effects isn’t made to animate characters, and the rigging and animation functions of Toon Boom and Moho are superior.” And what I usually say in response is: “Yes! You’re 100% correct. Toon Boom and Moho are unquestionably better options for ‘traditional,’ straight, narrative, 2d character animation. No argument there at all.”

So why do I use After Effects? And why rigged puppets? I’ve got a few pretty good reasons.

First, keep in mind that most motion designers are not going to be animating characters 100%, or even 50%, of the time. If all you do is 2d character animation — especially creating a series or long-form films or features — After Effects is probably a terrible choice. But for a motion designer, for whom 2d character animation is but a part of their workload, After Effects is a pretty compelling option:

- It is a software almost every motion designer learns, uses, and probably subscribes to (or their studio subscribes to). This means that for the motion design student studying character animation, there’s no new software to buy or learn. It also means that the studio they may work for doesn’t have to purchase anything new.

- Because almost all motion design projects are based — or at least finished — in After Effects, the motion designer using After Effects for character work will integrate more smoothly into the studio’s and/or project’s workflow, and make it easier for collaborators to work with them.

- Third-party scripts like Duik Bassel (which is comprehensive, free, and open source!), Joysticks ‘n Sliders, and Rubber Hose go a long way to make After Effects viable for character work.

- And why the rigged puppets? Many motion designers don’t necessarily have the kind of background in life and figure drawing that classically trained character animators do. Working with rigged puppets allows these students to begin working with the fundamentals of character animation immediately regardless of their drawing skills. However, I always strongly recommend that motion designers take life and figure drawing classes if they want to do a lot of character work.

On the 3d end, most motion designers favor Cinema 4D because of its amazing Mograph tools and other features that are tailor made for motion design. And although Cinema 4D might not be as perfectly structured for 3d character animation as Maya, its character rigging and animation tools keep getting better, and are more than serviceable for most motion design applications. And it even has a few advantages that motion designers can appreciate:

- Cinema 4D is fairly easy to learn, while Maya has a bit of a steeper learning curve.

- Cinema 4D is designed to be a more self-contained “single-user” experience, whereas Maya more definitively separates modeling, rigging, animation, etc. Thus Maya works better for larger teams and pipelines. Most motion design projects feature smaller teams for whom Cinema 4D’s structure is more efficient.

- As with After Effects, because so many individual motion designers and studios are already using Cinema 4D, it means using something that’s probably already available, and makes integration with the project’s or studio’s workflow easier.

Animators Assemble!

Although I think it’s important to understand the subtle shades of distinction between “pure” character animation and “pure” motion design, especially when creating work that might blend aspects of the two, clearly there are more overall similarities than differences.

We’re all using animation to communicate, whether it’s a story, an emotion, information, or an idea. We all study and practice design and animation principles. And when we animate characters specifically, we all want them to live and breathe and think and feel. No matter where we fall within the Venn diagram above, our job is to give our characters life!

.png)