The Dos And Don’ts Of Storyboarding: 10 Tips From Cartoon Network Artists

Log in to Annecy’s online platform, scroll past the glamorous talks with famous feature directors, and you reach this: a four-way masterclass about the unsung role of storyboard artists.

The Art of Storyboarding program from Cartoon Network brings together senior artists from the studio’s shows, who offer a range of views on what it takes to do this work well. One thing they agree on: storyboarders deserve more credit.

The four participants are Julia Pott, the creator of Summer Camp Island and a former writer on Adventure Time; Alabaster Pizzo, an indie cartoonist and storyboard artist on Summer Camp Island; Mic Graves, series director on The Amazing World of Gumball; and Chuck Klein, who has storyboarded on Gumball and many other shows, and is now supervising producer on Apple & Onion.

The participants pitch their advice to students and young artists, but a lot of it is relevant to seasoned pros. We’ve condensed the 45-minute talk into ten top tips:

1. Get to know your characters. Pizzo starts by drawing the designs a few times. That way, she comes to like them: “I almost get to know them personally.” Klein often acts out their gestures and expressions himself, at his desk or in front of a mirror.

2. Don’t start by drawing the scenes you like. That’s a surefire way to run out of time, says Pott. The ideal approach is to storyboard chronologically, without focusing too much on particular bits. If you’re not satisfied with a scene, leave it and keep going — “you’ll have time to come back to it later.” Pizzo starts by drawing overhead schematics of each scene: “It really is so helpful to keep things organized.”

3. Don’t get too precious about your work. Pott invokes a metaphor: “You should look at a storyboard like two doctors looking at a body they’re about to operate on. It doesn’t belong to anybody — you’re just trying to fix the body.” Graves notes that artists will always have to rework their storyboards, due to changes in script or staging, or for other reasons. “It’s part of the process.”

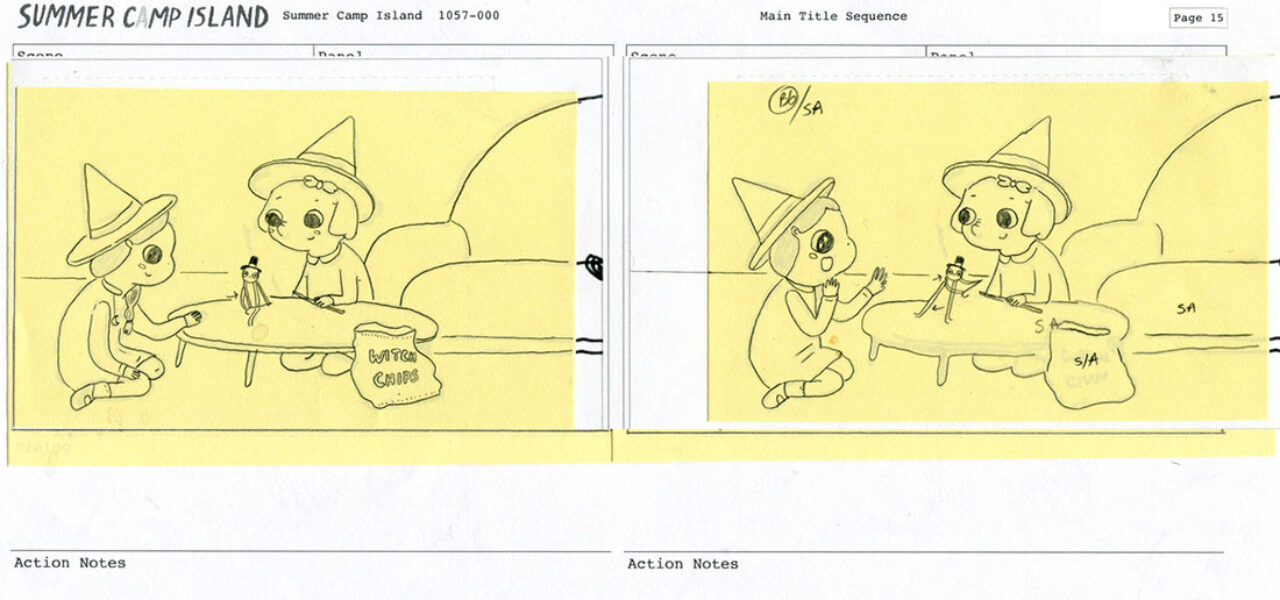

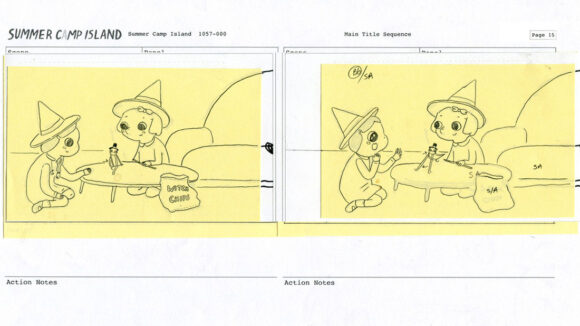

4. Sketch on post-it notes. Pott and Graves both swear by this method. “You can’t get too precious when you work like this,” notes Graves. “We work fast and we work small.”

5. Study cinema. While fine draughtsmanship helps, it isn’t crucial to the art of storyboarding, says Graves. The job is more “about being able to communicate your ideas.” He advises artists to spend time absorbing visual language. “If you understand film language … that’s just as valid.”

6. Don’t be too showy — especially in comedy. “If you stage something beautifully,” says Graves, “with dynamic angles and all sorts of stuff, that tends to overpower a joke.” Pizzo agrees that simplicity is key — it helps people further down the pipeline.

7. Get known. Pizzo suggests ways to put yourself out there: “Go to events, talk to people, get on social media, contact people who you think would be your peers, create a portfolio of work, post it a lot online, ask questions, ask about job openings.”

8. Be professional. Pott’s advice: “Be on time, clean up your boards, be a resource that people can go to and collaborate with.” Klein agrees: “Don’t phone it in. Don’t do just what it says in the script.” Oh, and hit the save button regularly. Pizzo has lost tons of work to power outages.

9. Stay motivated. In his youth, Klein was told by a producer that he’d “never work in this business.” He took that as a challenge and redoubled his efforts, and finally got a job in the animation industry aged 34. He admits that he doesn’t work as fast as some colleagues — “I struggle” — but his passion carries him through.

10. Make personal work. Pott recalls that she was constantly doing her own things between jobs. “All of my ideas and future work came from those personal pieces.”

(Image at top: Storyboard from “Summer Camp Island.”)

.png)