What’s That Crazy Drawing, or How I Came To Know and Love Animation Smears

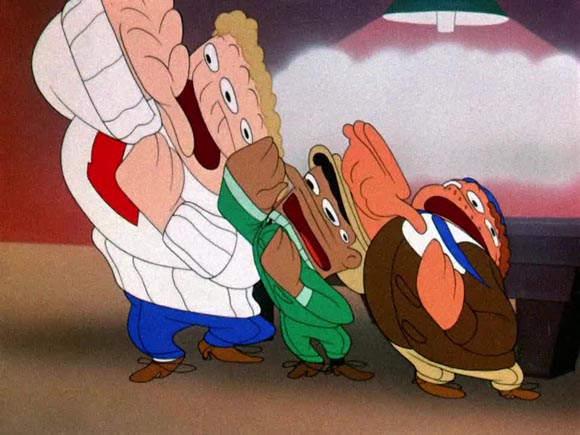

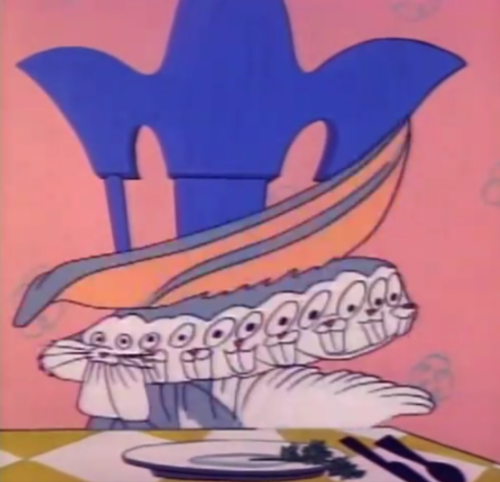

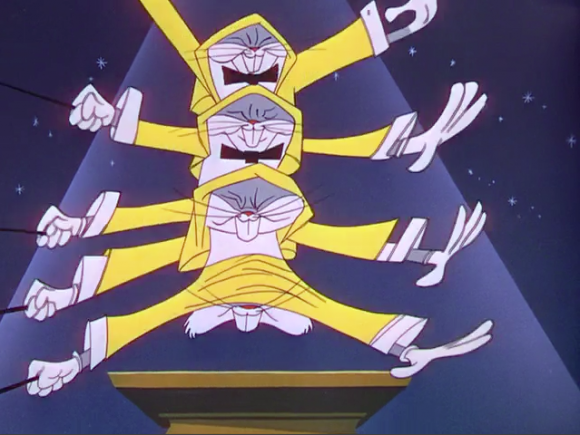

I didn’t really know about animation smears until college. It was a time when my passion for animation had just kicked into high gear, and once I learned how to convert my DVDs into Quicktime files, the flood gates opened. I was like a kid in a candy store, scouring through hours of animation every day. As I looked through the cartoons, I began to discover some odd things occurring. A character would look perfectly fine in one frame, but for a few frames it would turn into an absolutely insane-looking mutant, before suddenly reverting back to normal form. Without any understanding of what these were, I had discovered smears.

Around the same time, my second year animation teacher at the School of Visual Arts, Celia Bullwinkel, gave an in-class lecture about smears. She explained to us what they were, and what purpose they served. She screened a few smear-heavy Chuck Jones cartoons like The Dover Boys, showed some still-frame examples, and gave us an assignment to animate one ourselves. Of course, every budding animator thinks the same thing when they discover smears: “I CAN USE THESE FOR EVERYTHING!” But soon one learn that smears are best used judiciously; otherwise everything you animate looks like it’s made of Jell-O.

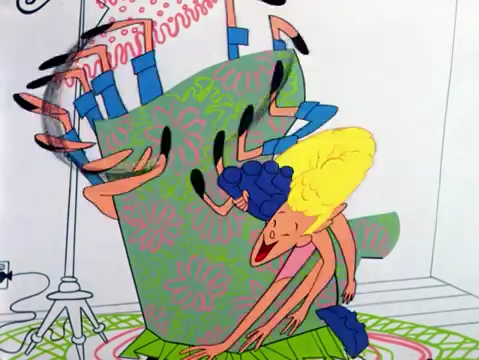

After some time passed, I began to appreciate smears outside of the context of animation, simply as still pieces of art. Somebody had to draw every one of these. It’s a truly creative and subliminal way of expressing artistic abilities, while at the same time serving the practical purpose of recreating an effect that happens naturally in live-action film.

Eventually, my friends said I should go ahead and make a blog about them, probably so that I would stop pointing them out while we were watching animated films together. So two years ago, I launched Smears, Multiples and Other Animation Gimmicks, never imagining that it would become as popular as it did.

Almost immediately after setting up my first post, followers started pouring in. I opened up submissions so that followers could submit their own images, and people began submitting smears from anime, foreign animated films, television shows, commercials, video games, Newgrounds Flash films, and even smears they had animated themselves.

As of this writing, the Smears Tumblr has over 110,000 followers. I’m sure many followers simply find the images hilarious, but I believe there are plenty of us out there who think they are much more than just funny images. Either way, I’m glad people get as much of a kick out of these as I do. Perhaps a few young animation fans have been inadvertently enlightened on how much art, creativity and hard work goes into creating animation. That’s a good thing, I think.

.png)