2026 Oscars Short Film Contenders: ‘I Died In Irpin’ Director Anastasiia Falileieva

Welcome to Cartoon Brew’s series of spotlights focusing on the animated shorts that have qualified for the 2026 Oscars. The films in this series have qualified through one of multiple routes: by winning an Oscar-qualifying award at a film festival, by exhibiting theatrically, or by winning a Student Academy Award.

Today’s short is Ukrainian director Anastasiia Falileieva’s I Died in Irpin, produced by Maur Film, Artichoke, and Plastic Bag Studio. The short qualified for the Oscars at the Bucheon International Animation Festival, winning the grand prize for a short film. It has since won five other Oscar-qualifying prizes at Clermont-Ferrand, Cinanima, Fest Anča, Manchester Animation Festival, and Animateka.

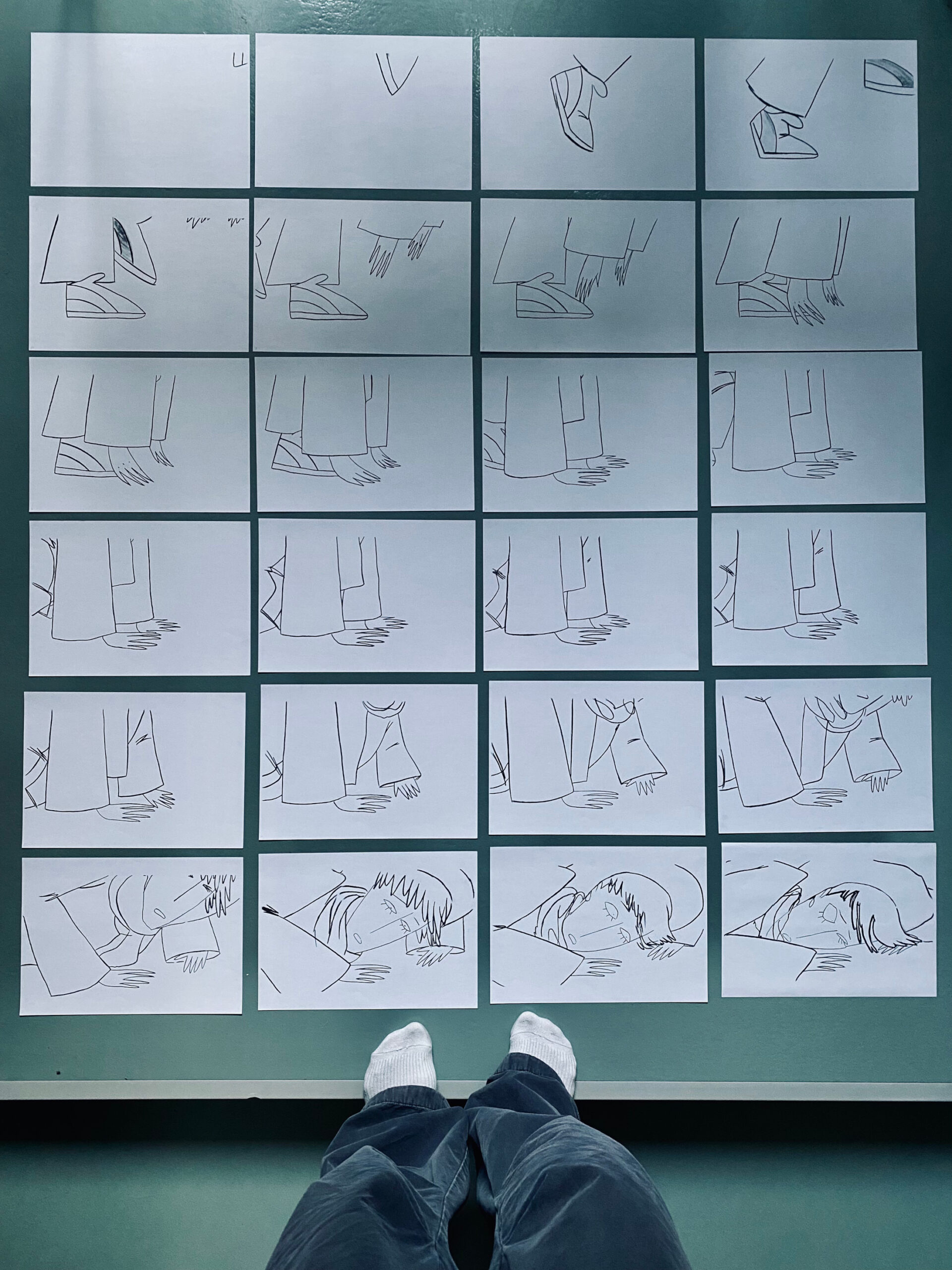

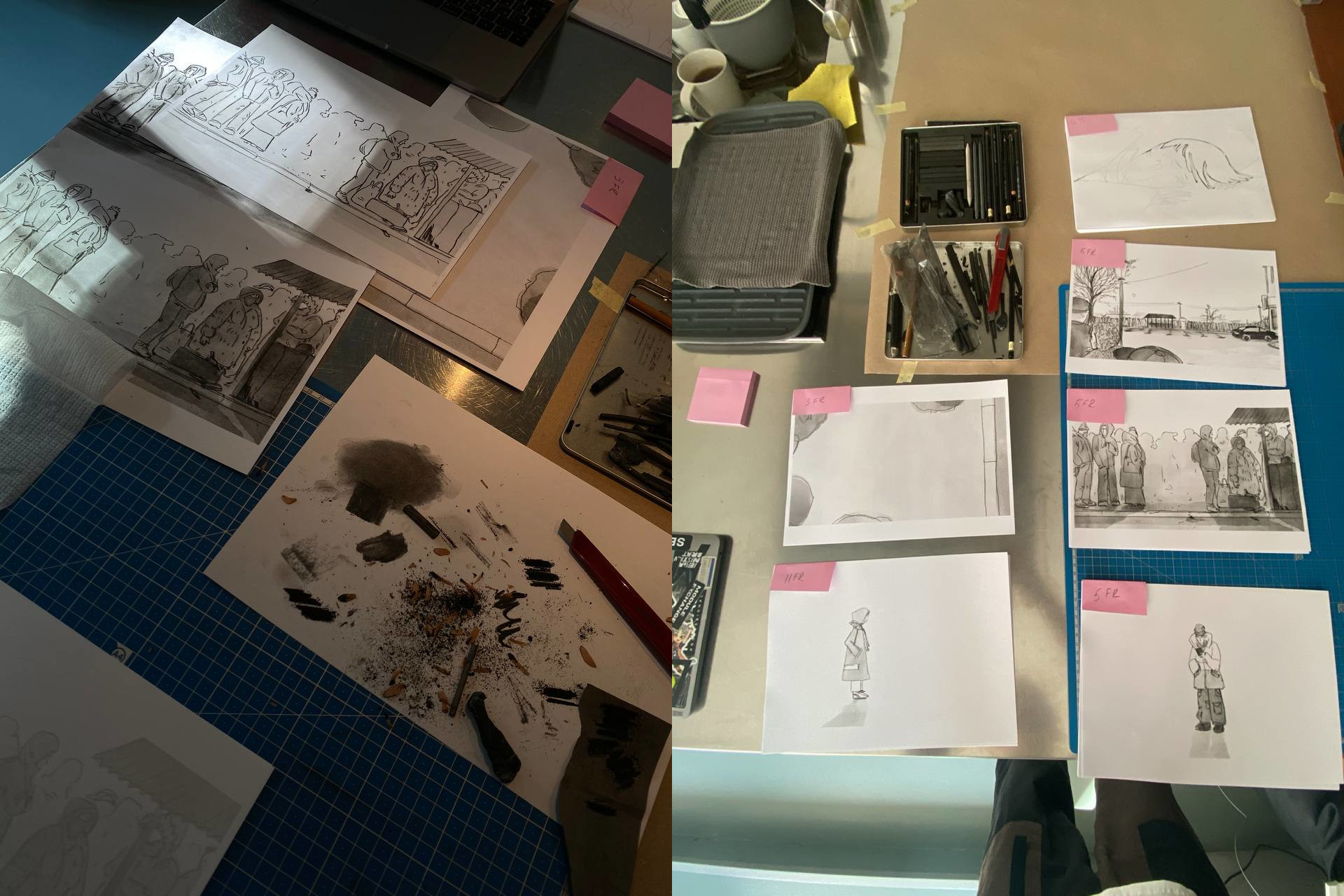

I Died in Irpin is an autobiographical animated documentary in which Falileieva retraces the disorienting days she and her at-the-time boyfriend spent traveling from Kyiv to Irpin after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, only to become trapped as conditions rapidly deteriorated. The film unfolds as a fragmented recollection of trauma, both from the emerging occupation and from abusive relationships, capturing how one can physically escape a place yet remain emotionally bound to it. Its charcoal, frame-by-frame animation on paper gives the story a haunting vulnerability: smudged lines, fading contours, and the constant risk of an image disappearing are ever-present. The result is a stark, resonant style that feels inseparable from the film’s themes, using the raw texture of charcoal to convey loss, resilience, and the lingering imprint of survival.

Cartoon Brew: What was it about this story or concept that connected with you and compelled you to direct the film?

Anastasiia Falileieva: At the moment when we were leaving Irpin, I was praying for the first time in my life and swore to God that if I survived, I would make the movie about it. Cinema has always been my coping mechanism. In the beginning of the film, there is live footage of the Motherland statue in Kyiv – I shot this in the first hours of the full-scale invasion. I was so shocked that Russia so openly attacked Ukraine that I decided to turn my experience into a documentary. It was the only possible way to process the reality without going insane. And making the whole film out of it was the only way to survive the trauma of war and abuse.

What did you learn through the experience of making this film, either production-wise, filmmaking-wise, creatively, or about the subject matter?

I learned a lot about this relationship and about myself. Making the film was highly therapeutic for me, and at the beginning of production, the story was less about abuse and more about a survival chronology. During the process, we shifted the spotlight a bit, and it made the story more multidimensional. Also, I felt very heard. The whole team was — and still is — so tender and supportive of the film that it became very natural to open up, and I am eternally grateful for that. The success of the film gave me confidence that this story is valuable, but at the same time, unfortunately, showed me how many people ended up in a similar situation, especially women.

Can you describe how you developed your visual approach to the film? Why did you settle on this style/technique?

Shortly after we left, we discovered that the house had been completely burned down by a Russian missile. After the city was de-occupied, its remains were found stuck in the yard. That was the moment I understood that the animation must be made only in charcoal. At first, I wanted to use the real ashes of the house for the film, but it was obvious nobody would allow me to do that. The story is as fragile, dirty, and complicated as this medium. It is hard to work with charcoal and keep it consistent; everything smudges and is easily destroyed, just like the memories of those highly traumatizing events.

The film reconstructs your personal experience of fleeing from Kyiv to Irpin and spending time in a basement as the invasion progressed. How did you decide which memories to include or omit in those ten days?

I picked only the most vivid and important memories, those that had proof. I was really afraid to include anything that wouldn’t be true because my ex gaslighted me a lot about everything, so I became very keen on fact-checking. Also, my memory was so damaged and blurry that I definitely needed key points to stick to. So I used my photos, videos, and messages a lot to reconstruct the chronology. But some things are just unforgettable: the Russian fighter jet rumbling above my head, the overwhelming whistle of a mine flying nearby, hours spent in an endless evacuation convoy.

.png)